How Marsha Hunt fought Hollywood blacklisting

- Published

It's 70 years since Red Channels was published in the USA - a directory of writers, actors and producers alleged to be communists or communist sympathisers. The red scare ended many careers. Now 102, actress Marsha Hunt is almost the last person still alive named in the book.

Marsha Hunt never wanted to do anything except act. Born in 1917, she grew up in New York City and remembers going to the theatre with her father when she was five.

"It was a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta - probably HMS Pinafore. I turned to my dad and I said I'm going to do that. After that if there was a play I was always in it," she says.

Hunt was in her late teens when she went to Hollywood looking for a film career. She found success quickly: her first film was The Virginia Judge in 1935.

She was constantly in work and seemed to have a long career ahead of her - although few of her early films are familiar today. An exception is the 1940 version of Pride and Prejudice with Laurence Olivier.

She still regrets a near miss with the classic Gone with the Wind. "For about a weekend it appeared I'd been cast as Melanie, who's Scarlett O'Hara's cousin. Then an executive changed his mind and I lost the role. When I went to Hollywood I'd been warned I would have my heart broken and losing Melanie was that moment."

But before she was 30 Marsha Hunt had made more than 40 films. Producers valued her attractive and intelligent screen presence.

In 1945 she was asked to join the board of the Screen Actors Guild and for the first time her politics came under scrutiny.

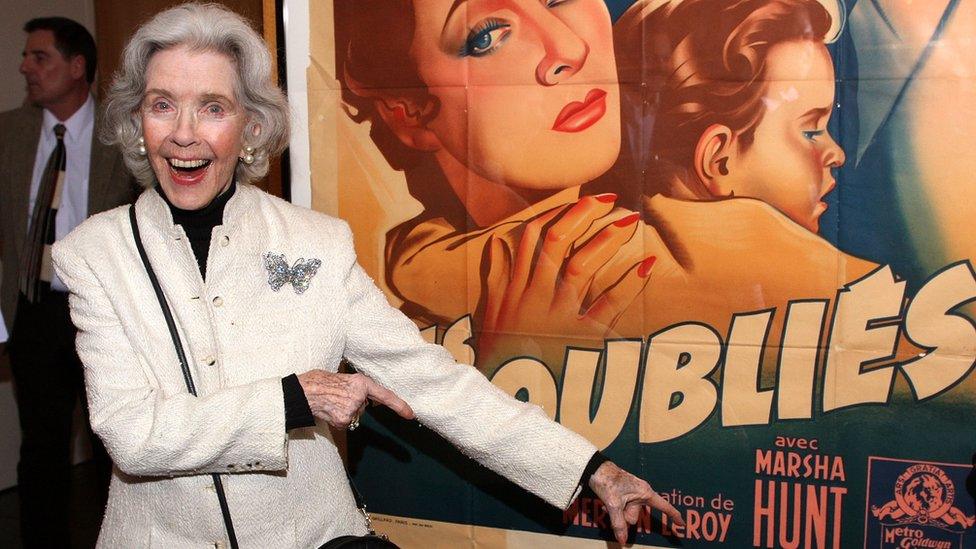

Hunt was pictured at The Art of the Movie Poster exhibition in 2010

"I was proud to be asked. To have a voice in what would affect all screen actors was dazzlingly important to me," she says. But Cold War tension was building with the Soviet Union and anyone suspected of left-wing sympathies was open to attack.

Hollywood, radio and TV came under suspicion. The political pressure came from HUAC - the House of Representatives Committee on Un-American Activities.

In 1947, HUAC summoned 10 writers to Washington to testify. Each was asked if he was a communist and all ultimately went to prison for refusing to answer or to name other communists.

Marsha's problems with the authorities may have begun when she joined the Committee for the First Amendment - a group of liberal actors who supported the Hollywood Ten. Among those who flew to Washington were Danny Kaye, Gene Kelly and John Huston. Also there were Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart, married and the biggest stars Warner Bros had.

"We were a brigade to defend those who'd been blacklisted or were under suspicion," Hunt remembers. "We were serious citizens trying to set Washington straight: we were not a bunch of Reds. We were headed by the Bogarts so we were a pretty spiffy team.

"We made our speeches and did a radio programme called Hollywood Fights Back and came home thinking we'd been patriots and had defended our profession. If there were some communists among us that was their business and not ours.

"I knew nothing about communism but I just thought that as it was a legal party other people had the right to join the darned thing if they wanted to. But it was a time of hysteria and all of us who spoke out against blacklists were punished in some way or other. There was a very strong right wing in the movie business."

Hunt says she "certainly lost a lot of jobs as the blacklist tightened"

Stars who'd supported the committee quickly came under huge pressure from studio bosses to recant and Humphrey Bogart declared that his support had been a mistake.

Hunt remembers that turnabout with sadness. "I'm sorry to say but it can only be cowardice. That's a terrible word to use about the Bogarts but why else would they do that? We all went to Washington to defend other people's rights. It was a time of people really turning quite ugly."

She says it's hard to judge how far her career was damaged at first. But in 1950 her name and 150 others appeared in Red Channels, a 200-page book published as an adjunct to Counterattack - The Newsletter of Facts to Combat Communism. The book was subtitled: "The report of communist influence in radio and television." Inclusion was enough to damage or in some cases terminate a career.

Those named included composers Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland and Marc Blitzstein, actors Lee J Cobb and Jose Ferrer and the writers Dashiell Hammett and Lillian Hellman. Today the only survivor apart from Hunt is Walter Bernstein, who's 100. (In 1976 Walter Bernstein wrote the film The Front about the blacklist era.)

Hunt insists that in 1950 she never even saw Red Channels. "I guess I was a star but I was never sizzlingly hot as a Hollywood property for hire. But I certainly lost a lot of jobs as the blacklist tightened.

"We live, we proudly insist, in a free country. By that was meant, I was sure, that you were free to your opinions and actions if they didn't break any law. The anti-Reds were fighting Americans' freedoms. I didn't know the first thing about communism - never studied it, never learned about it. I must have known a few communists but I didn't care - that was their business, not mine."

To continue to work on screen her agent persuaded her to write out a statement of her beliefs. "It was an anti-communist declaration and he said without it I would never clear my name. Gradually it changed things for me in Hollywood but my work and reputation never returned to how they were."

Hunt says she was never at the top of anyone's list of people to attack. "But there were actors I worked with and liked who were or had been communists. I'd been seen in the company of so-and-so and that was enough.

"Suddenly to have the dirtiest word in the American language - communist - held against me was an outrage. And I had no way to end it or fight back."

After 1950 screen credits were mainly limited to TV but she was happy to appear in George Bernard Shaw's play The Devil's Disciple on Broadway, where the power of the blacklist was less absolute. Other stage-work followed.

By the '60s she was working primarily for charitable and humanitarian causes although occasional screen credits continued. Though she largely disappeared from public view she was pleased when director Roger Memos made the documentary Marsha Hunt's Sweet Adversity, which is introducing her to the online generation.

"Many younger people know little about the Hollywood blacklist," she says. "Sometimes I'm asked if it could ever happen again. I hope America learned from what happened all those years ago. But how can you ever be sure?"