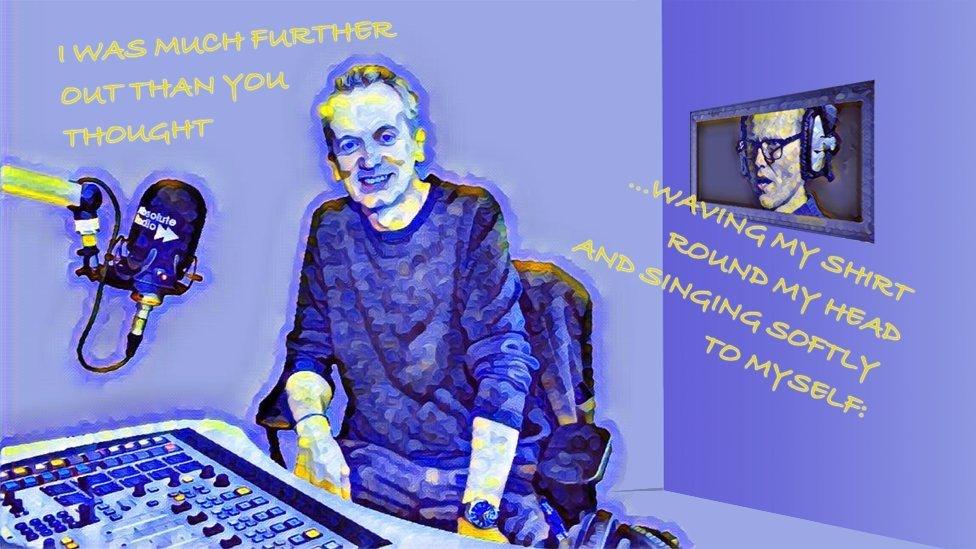

Frank Skinner: Will Gompertz reviews the comedian's poetry podcast on Absolute Radio ★★★★☆

- Published

Odd combinations have long been a staple of the entertainment industry. For those old enough to have seen it (still available on YouTube), who can forget Prince Edward's cringe-inducing toe-dip into television production with the culture-clash that was It's A Royal knockout? Not the Queen, that's for sure, who went on to show her youngest son how to play the incongruous card with her winning James Bond spoof at the London Olympics.

The Royal Family's infamous day out at Alton Towers was in 1987, 30 years after the comedian Frank Skinner was born, a fact I learnt from listening to his new podcast, which is another example of the light-entertainment-meets-highfalutin genre.

Frank Skinner's Poetry Podcast, external is knowingly tapping into the surprising-juxtaposition game, following the likes of Lenny Henry who has successfully evolved from kids' show clown to serious Shakespearian actor.

"Yes, yes, poetry" Skinner says in his introduction, acknowledging it might seem an unlikely subject for a man still shaking off a '90s laddish image.

The comedian and actor, Frank Skinner says he developed his love of poetry while studying English at Birmingham Polytechnic

Actually, it's not in the least bit strange that he should be drawn to poetry or Lenny Henry to Shakespeare.

There are two common attributes shared by the majority of successful comedians: the first being an intellectual curiosity, and the second, an understanding and appreciation of language and its use.

It is a mark of how the Arts have allowed themselves to become segregated - broadly along class lines - between what is seen as cheap entertainment and classy culture.

It is a perception, not a reality.

Rock, pop, and rap are as worthy an art form as classical music, and stand-up comedy could justifiably be considered performance art. The division between the different artistic forms of human expression is a nonsense.

Frank Skinner shouldn't have to defend his love of poetry, nor the fact that he is approaching it as a fan and not as an academic.

Poetry and comedy are natural bedfellows - a fact that Skinner demonstrates in this one-man-no-guests podcast peppered with amusing asides and left-of-field references - from the absurdist dramatist Eugène Ionesco to a whippet dog called Frank Skinner.

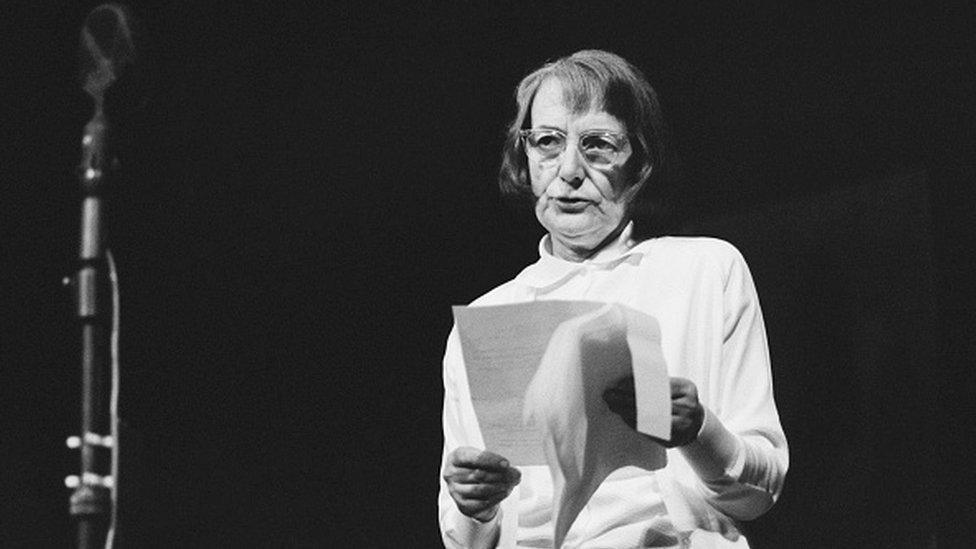

First up on the first episode of the first series (I hope there are plenty more) is the 20th Century British poet and artist Stevie Smith (1902 - 1971) and her 1957 classic Not Waving but Drowning, external, a three-verse meditation on someone with a jolly public persona hiding a desperate soul:

Nobody heard him, the dead man,

But still he lay moaning:

I was much further out than you thought

And not waving but drowning.

Skinner's approach is to personalise the poems he discusses, arguing, not unreasonably, that his response is a coming together of his viewpoint with that of the poet.

It's a familiar argument made particularly well in an essay called the Creative Act, written by Marcel Duchamp in the same year as Smith produced Not Waving but Drowning.

Stevie Smith's Not Waving but Drowning was first published in 1957, and was voted Britain's fourth favourite poem in a poll in 1995

It is a very good poem, the title of which has become part of our everyday lexicon. I remember sitting on the beach at Bude in Cornwall, keeping half an eye on my kids bodyboarding while staring out at sea and contemplating what flavour of ice-cream I fancied. I saw a woman waving from her surf board and mentioned the friendly gesture to my wife, who, paraphrasing Smith, said "she's not waving, she's drowning".

And so she was. Two guys in red swimming trunks, neither of whom looked remotely like David Hasselhoff, surfed out and rescued her. It was very dramatic, but not, Skinner speculates, the real subject of Smith's poem.

It is not literally about drowning at sea but a distant character who stands outside the swim of daily life: a man who - to all appearances - is waving enthusiastically when in reality he is drowning in obscurity ("I was much further out than you thought" the dead man reports). This Skinner can relate to, and tells us the thing he most enjoyed about being famous, was neither the money nor the trappings, but being noticed, being "heard":

I was much too far out all my life

And not waving but drowning.

It is not easy to relay the meaning and rhythm of poem while retaining a voice that doesn't sound like a cliche of a worthy 1970s round-table poetry group.

Skinner nails the task, bringing the poet's words to life before veering off on an anecdote or explaining that poetry is broken up into lumps known as verses (fancy language is banished, which is why, perhaps, he chose Smith who used simple language to communicate ideas and feelings of great complexity).

The show is not perfect, but then it is only one episode old.

Having got our attention and established his chatty approach, there's scope for Skinner to go a little deeper into the text.

Not Waving but Drowning is a timely poem to study, not just because it speaks to our current anxieties, but also that in 12 short lines Smith introduces three separate voices who tell us the ambiguous story in words chosen specifically for their weaselly slipperiness.

Fake news, and all that.

There is also room for a bit more biographical detail. Obviously, this is Skinner's informal take on poetry, with the way it touches him a large part of the show's structure, but it could be rebalanced to allow the poet to share some the limelight.

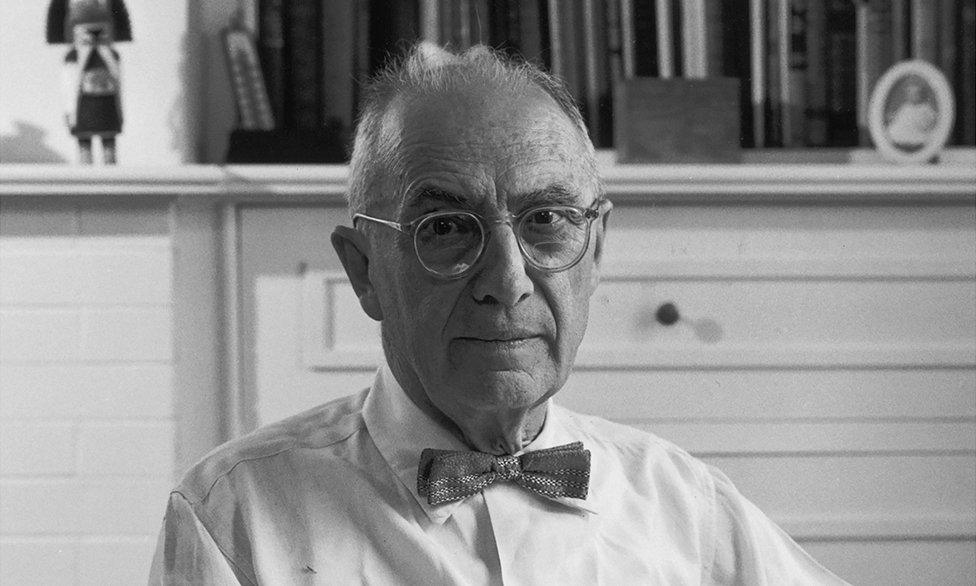

We learn very little about Smith, and almost nothing about William Carlos Williams (1883 - 1963), the American modernist poet who wrote Skinner's second choice of the week, Danse Russe, external (1916).

The American poet, William Carlos Williams once wrote "The purpose of an artist, whatever it is, is to take the life, whatever he sees, and to raise it up to an elevated position where it has dignity"

It is another terrific selection.

A little longer than Smith's, but not by much. It shares the subject of loneliness, but from the other side of the desolate coin. This time our male protagonist is watching the sun rise as his wife and children sleep. He is enjoying a moment of sensual euphoria, suppressed from full expression perhaps, to keep the genie of his genius in the bottle:

"I am lonely, lonely.

I was born to be lonely,

I am best so!"

If I admire my arms, my face,

my shoulders, flanks, buttocks

against the yellow drawn shades,—

Who shall say I am not

the happy genius of my household?

It would have helped to have some biographical detail; to have known that Williams was a paediatrician by day and a poet by night (the genius of the household?): that he was searching for a new American idiom that established a language independent from European influences, and that the poem was indebted to the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé's L'après-midi d'un faune (Williams spent time living in France).

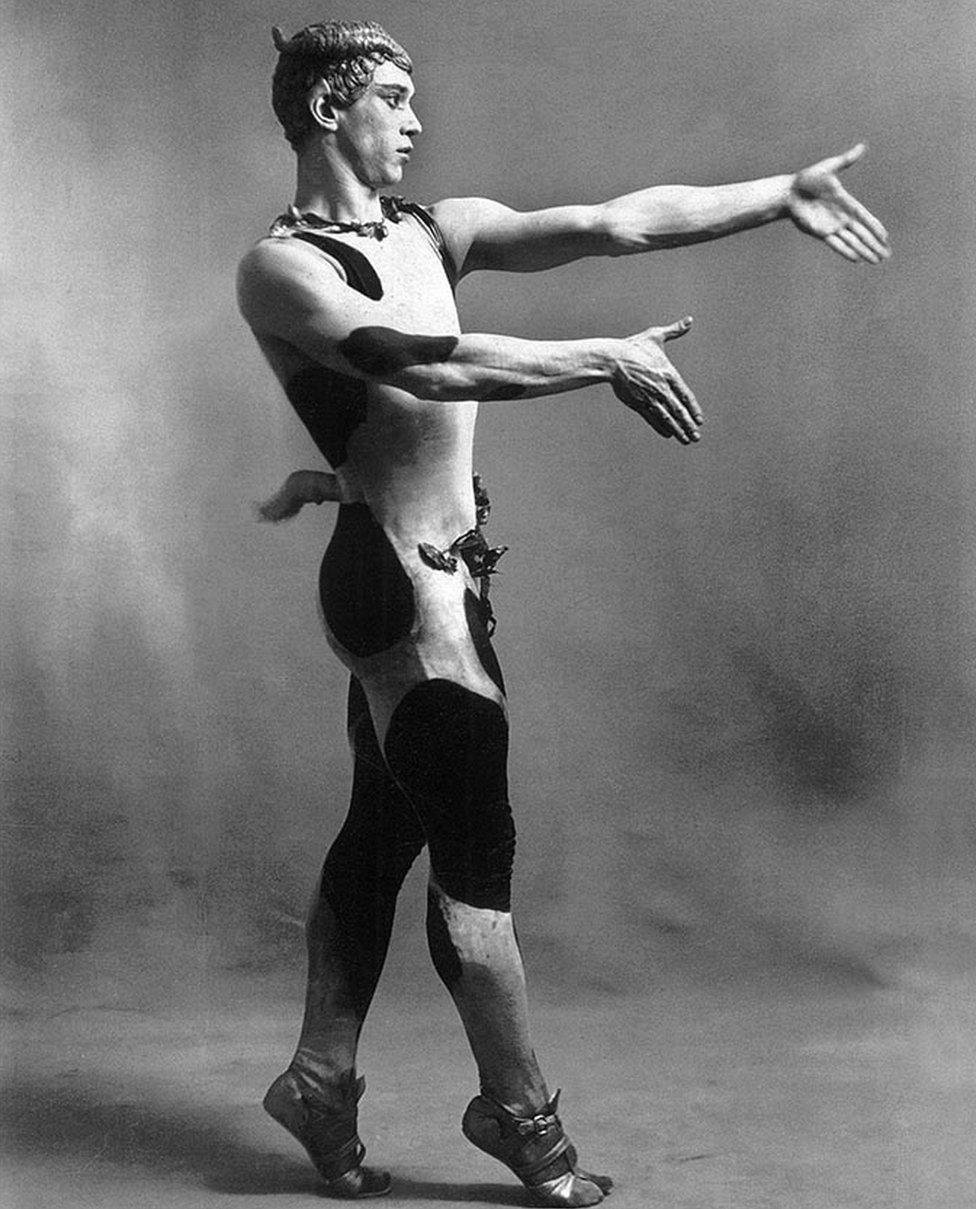

Claude Debussy then wrote a piece of music in response to Mallarmé, which was subsequently turned into a dance for the Ballets Russes (hence the title of Williams's poem) by Vaslav Nijinsky, which Williams saw performed in New York having known it'd caused a furore in Paris years earlier when Nijinsky started writhing in ecstasy, alone on the stage, to howls of derision and gasps of delight.

The influence of Stéphane Mallarmé's poem L'après-midi d'un faune can be seen in William Carlos Williams' Danse Russe

Vaslav Nijinsky choreographed and danced in L'Aprés-midi d'un faune for the Ballets Russes in 1912, which William Carlos Williams saw years later

Skinner only touches on this back story and isn't entirely accurate on all his factual details (I don't think Williams lived in New York, he was a man of Rutherford, New Jersey). To an extent that's forgivable, our host says he doesn't go much for background info because he wants to have a relationship with the work of art not the person who made it or what might have influenced it. He then humbly adds, "that might be an error on my part".

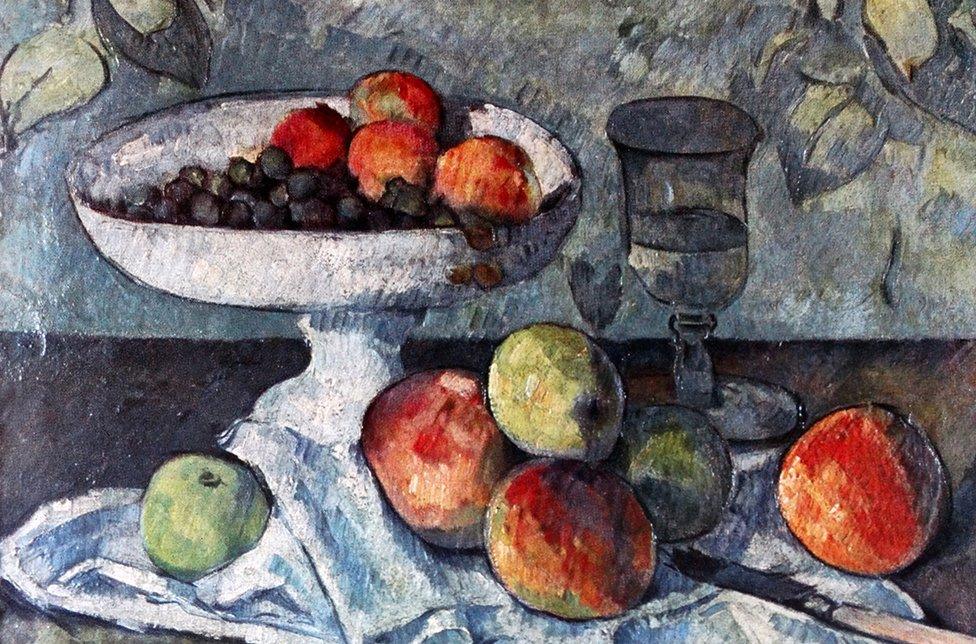

I suspect it is. The more you repeat read a poem, which Skinner rightly encourages us to do, the more you want to comprehend, and that usually means going beyond the page to the person holding the pen. That's the way into the rest of the writer's work, and the discovering of little jewels like Williams's This is Just to Say, external, which for some reason reminds me of a Cezanne still life:

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

Paul Cézanne's Still Life with Fruit Dish (1879-80)

First-episode teething troubles are to be expected and should not detract from a very welcome new addition to the cultural landscape: a simple idea without any fancy production presented by someone who brings insight and enthusiasm to an art form that is enjoying a resurgence in popularity.

Roll on Monday for the second instalment.

I think it's going to get better and better.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external