Jiab Prachakul: Will Gompertz reviews BP Portrait Award 2020 winner ★★★☆☆

- Published

Jiab Prachakul won the BP Portrait Award 2020 for Night Talk, which judges described as an "an evocative portrait of a fleeting moment in time"

The working life of the professional portrait painter was put in jeopardy by what must have been the thoroughly unwelcome advent of photography. What was your mid-19th Century artist to do? The camera was faster, cheaper and better at capturing a likeness. One day their studio was packed with Lady This and Lord That posing in their finest clothes, the next they were painting tumbleweed.

And then, just in the nick of time, some brilliant young artist - probably not so fresh from the brothels of Paris - realised that photography didn't herald the death of painting at all, in fact, it had set it free.

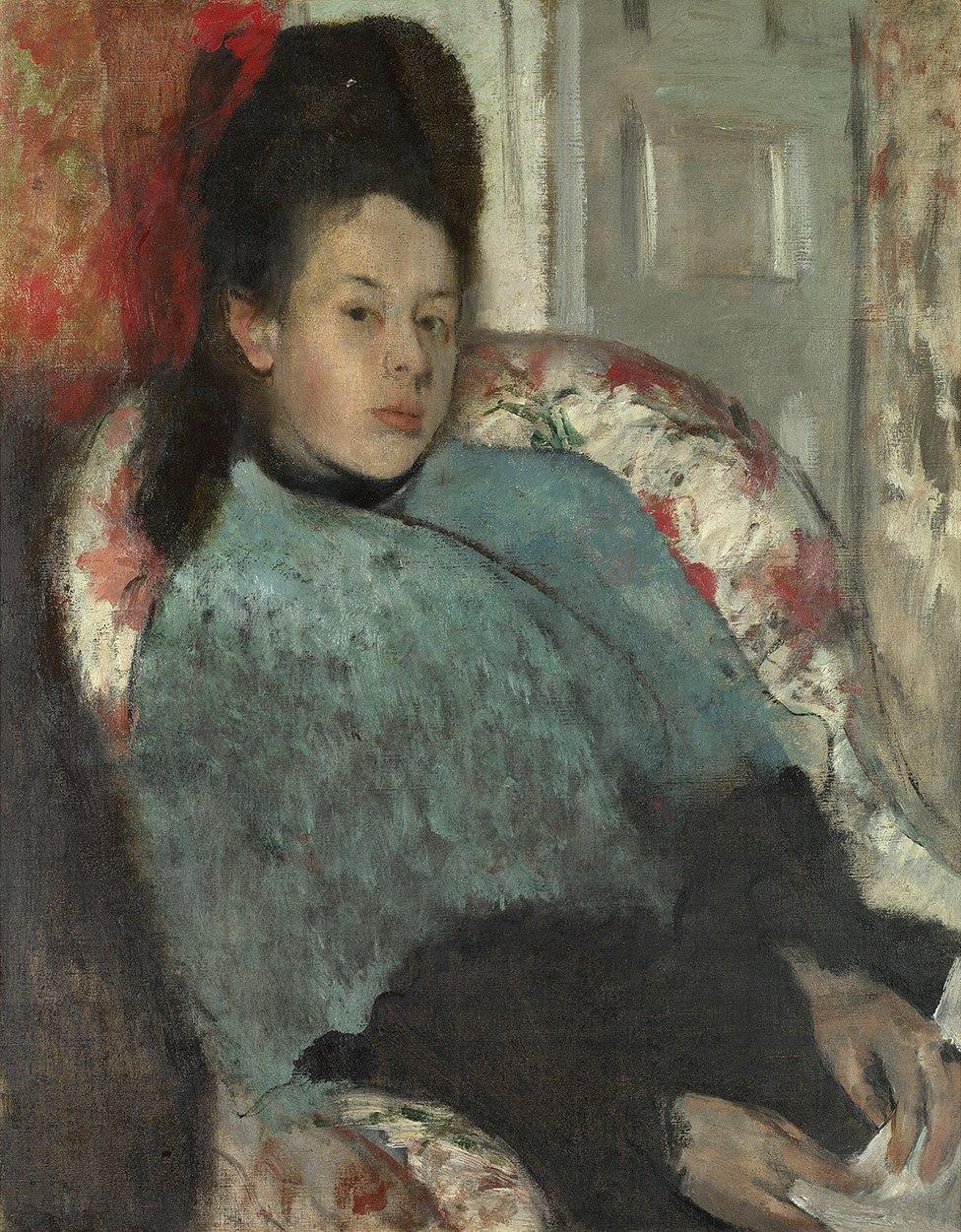

Convention went out of the window, along with the Victorian backdrops and fake backgrounds of rolling pastures. In their place came a new wave of radical artists with not-so-radical names like Edgar, Claude and Paul who would take portrait painting to a place it had never been before: the sitter's soul.

Edgar Degas, Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne left the dull business of superficial representation to the one-eyed machine with a mechanical lens, while they got on with the important task of painting the person, inside and out. They developed a less-is-more style, removing all the extraneous detail of an old-fashioned portrait, which rendered the picture lifeless, and instead created simplified images that revealed the subject's character.

Claude Monet mastered the art of looking beyond the surface, as in Portrait of Père Paul, 1882, at Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna

They showed that a single expressive brushstroke could say more about someone than any photograph or old-school portrayal.

Impressionism was born.

But not without first going to the photographer's studio on a dawn raid, where they learnt how cropping a picture can create dynamism and a feeling of instant creation.

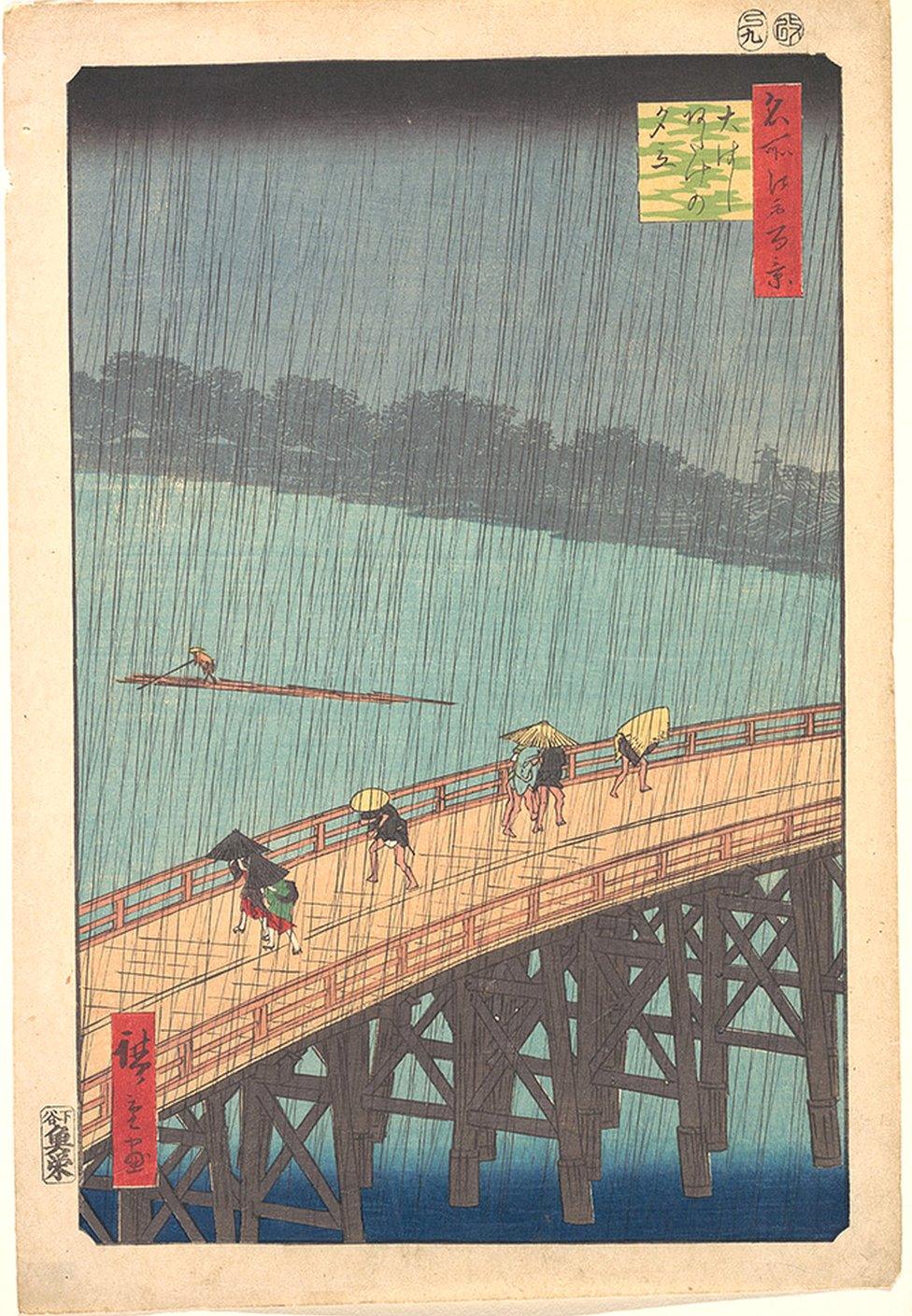

This was Degas's stock-in-trade, along with an elevated vantage point, a technique he copied from Japanese ukiyo-e artists like Utagawa Hiroshige.

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake by Utagawa Hiroshige, whose skilful use of the raised vantage point influenced Degas

It was this combination of aesthetics from east and west that led to modernism and the art of today.

It is evident everywhere you look, from David Hockney's Swimming Pool pictures to Jiab Prachakul's painting Night Talk, which won the Thai-born, Lyon-based artist this year's BP National Portrait Award, and with it a cheque for £35,000 and the guarantee of a future commission from the National Portrait Gallery (NPG).

Thai-born Jiab Prachakul says of the friends she painted "We are all outsiders, and their friendship has offered me a ground on where I can stand and embrace my own identity"

Night Talk could be a work of Parisian Impressionism circa 1874 if it wasn't for the acrylic paint (only became available in the 20th Century) and the Berlin setting.

It depicts two of the artist's friends sitting at a low wooden table, looking glum. They are both dressed in black, a colour repeated in the vase in the foreground, which serves as a navigation tool for our eyes as we scan the picture. The painting has more than an echo of Degas, both in terms of composition and subject matter: artists taking a break (one is a Korean designer, the other a Japanese composer).

Degas was a big influence on Hockney who was, in turn, a big influence on Prachakul, who says it was the Yorkshireman's 2006 exhibition at the NPG that made her realise she wanted to be an artist (she started out in film as a casting director).

Portrait of Elena Carafa, c. 1875 by Edgar Degas, who had a major influence on David Hockney

Jiab Prachakul had the "instant realisation" of wanting to be an artist, after seeing the Hockney retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery

Fourteen years later she returns triumphant as the winner of its portrait prize, an achievement that has been overshadowed by two news stories. Firstly, the prize is sponsored by BP, a decades-old arrangement with the oil and gas giant which has now become highly contentious - not to say toxic - as artists and others lobby the NPG to end the relationship. And secondly, due to Covid-19, there will be no physical BP Portrait Award show in 2020.

Instead there's a perfectly serviceable virtual show online, which is all that can be done in the circumstances but is obviously not the same.

You can see BP Portrait Award 2020 at the NPG's online show

It makes critiquing the picture difficult.

As the Impressionists knew, there's a big different between a photograph and a painting, even when it is a photograph of a painting, which is what I'm looking at like everyone else. Any sense of scale is lost, as are the material and technical qualities to which you immediately respond (or don't) when seeing an artwork in the flesh.

It is clearly an accomplished piece of work. The foreshortening of the man's hands, the colours and patterns of the table top mirrored in the protagonists' faces, and the tautness of the composition with its geometric structure are all noteworthy.

It's good.

But I'm not sure if it is great.

Maybe it would be different when seen hanging on a wall, but Night Talk doesn't appear to have the palpable psychological charge that makes a memorable picture, it lacks the atmosphere that gives life to a work by Degas or Hockney. The female figure feels a little flat, her expressions cartoon-like. The facial emotions of the man have more depth but the highlights around his left cheek and the bridge of his nose aren't quite right. Nor are their clothes.

Black is a notoriously difficult colour to master.

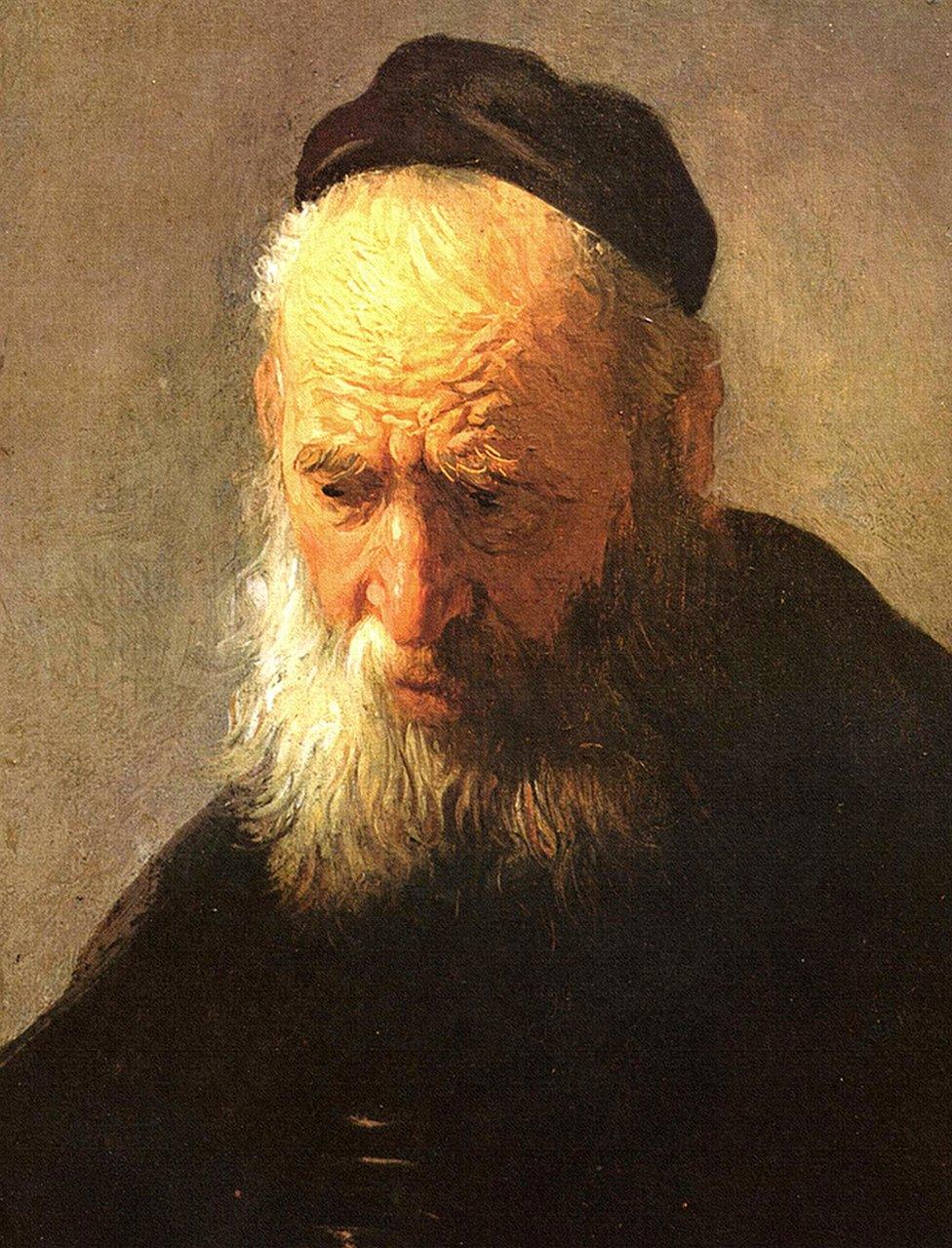

Titian, Rembrandt, and Manet have all done it, but then they are the best of the best.

Head of an Old Man in a Cap (circa 1630) by Rembrandt, who was a genius in his use of black

There's nothing wrong with Prachakul's line, which is confident and flowing, but the shadowing and tonal transitions don't appear to be of the same technical quality. There's also a slight visual awkwardness in the way the top of the bar cuts across the café dwellers' necks.

That said, there is plenty to admire, not least the way the three separate flower arrangements form a v-shape to frame the two characters, which is mirrored by their outward-facing crossed legs. It gives the painting a pleasing symmetry, while also suggesting a feeling of discomfort and alienation.

Much has been made of the fact Jiab Prachakul is self-taught, which puts her in good company along with the likes of Vincent van Gogh and Henri Rousseau. They both used their lack of formal training (Van Gogh had some) to take painting in a new direction, to uncover universal truths through apparently naïve imagery. Van Gogh did it with his warped lines, Rousseau with his surreal jungle images.

Prachakul could do it too, but she needs to get inside our heads as well as her own and the sitters'.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external