Why we need a say over public statues

- Published

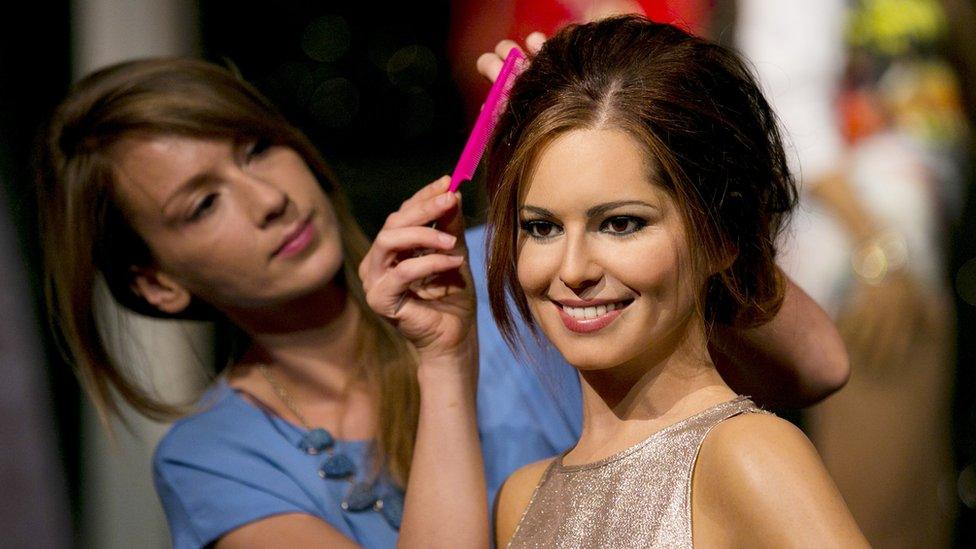

Typically, there are two kinds of Madame Tussauds news stories. The first is when there's a new waxwork made of a recently established celebrity (Dua Lipa). The second kind - which is way more fun because it's ripe with schadenfreude - is when a once famous person (Cheryl Cole) is removed because they have reduced currency in the public imagination.

There's nothing malicious in the decisions, it's business. If Madame Tussauds wants to stay relevant, and therefore solvent, it has to keep up with the times. Nobody is going to queue for hours on one of London's most polluted roads while the rain lashes down on their battered brolly to see a waxwork of someone in whom they have no interest, or possibly actively dislike.

So, it is 'Yes' to Harry and Meghan (recently removed from the royal section) and 'No' to Jimmy Savile (melted down in 2012). Notwithstanding your intellectual or aesthetic reservations about Tussauds, you have to admit there is a logic to the visitor attraction's exhibition strategy.

Cheyl Cole's statue was removed from Madame Tussauds last year

The same cannot be said for the country's approach to sculptures exhibited outside, in the public realm, of which there are thought to be around 20,000 - or 19,999 after the bronze likeness of slave trader Edward Colston was dispatched into Bristol harbour this weekend by protesters at an anti-racism demonstration.

Whatever your opinion of that particular incident, it highlights a broader issue, which is a lack of open public debate about the thousands of statues installed in community spaces across the country. Should the citizens who live and use those public areas not be part of a discussion regarding the artworks selected for display? If the vast majority find an existing sculpture objectionable, why should they be subjected to its presence every day?

Maybe, there's a good reason for a statue to remain. Fine. Let its merits be debated, and a democratic decision made on a way forward. Perhaps it could be re-sited, or contextual material added, or, in some cases, put in storage and the space used for an alternative artwork agreed by the local community. Any which way, give the people a say: who or what do they want to commemorate or celebrate?

But, unlike Madame Tussauds, there is no overarching national strategic approach to the display of statues in public places. There is the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association, but it has no official mandate to make curatorial choices or impose policy. The decision is usually left with local councils, some of which have truly awful taste. Or, worse, are deaf to the community they represent.

Perhaps there should be an authorised body overseeing a coherent policy for sculpture in the public realm: a body consisting of experts that could constantly review the works exhibited just as the curators in a museum do for the objects for which they are responsible.

This informed, dedicated body could also be a place for debate, commissioning, programming, and exchange. Sculpture in the public realm could be treated like another national museum, with a director, specialist curators, conservators, and - most importantly - an education department that could collaborate with the local community and schools.

It could provide more than a platform for discussions about what individual statues should and should not be shown, but also the chance to develop an exhibition plan in consultation with each area that would aim to enhance public spaces for the local population.

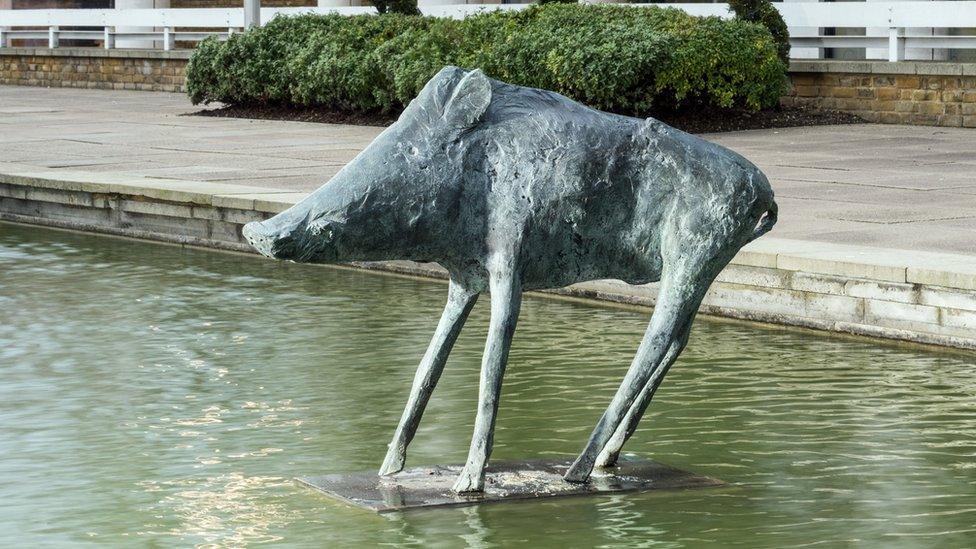

The toppling of Colston's effigy could be the catalyst for a new community-focussed approach. As towns such as Harlow in Essex have shown, with its commitment to British modern sculptors such as Elisabeth Frink and Barbara Hepworth, a serious, planned approach to the exhibiting of outdoor artworks can not only enhance the space in which they sit, but also the area as a whole - giving it an identity and a cohesion: a reason for people to live there and a reason for people to visit.

There is an opportunity to recast our approach to public sculpture, to transform the current hit-and-miss, generally unaccountable system, into a mould-breaking, country-spanning, new national Museum of Art in the Public Realm.

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published8 June 2020

- Published8 June 2020