What really happened at Nuffield Southampton Theatres?

- Published

The NST city centre theatre opened in 2018

The Nuffield Theatre in Southampton became headline news on May 6th when it filed for insolvency. The administrators blamed Covid-19 for its demise, and in so doing sent shock waves across theatreland, causing producers from London's West End to the country's regional playhouses to shudder with fear. Would they be the next victim of the pandemic? All agreed the closure was a terrible shame. But what very few knew was, it was also entirely avoidable…

Greg Palfrey is a Southampton man. He went to university in the city, then stayed in town and trained there as an auditor before deciding to specialise in insolvency… in Southampton, of course. He is still there today, more than 30 years later, heading up the Restructuring and Recovery department at Smith & Williamson, the firm of administrators overseeing the sale of the Nuffield Southampton Theatres' (NST) assets.

It was he who struck a sympathetic tone for his highly regarded local theatre, saying it had: "In line with other performance venues, suddenly found itself with unprecedented pressure on cash flow in the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak - a flood of refund requests and little in the way of advanced bookings." Palfrey's expert analysis of the situation was picked up by the press.

The Guardian wrote, external: "Nuffield Southampton Theatres (NST) has gone into administration as a result of the increasingly severe financial impact caused by coronavirus".

The Stage newspaper tweeted, external: "Nuffield Southampton Theatres has gone into administration due to the Covid-19 crisis, with administrators branding it 'a sad day not only for Southampton […] but for the country's theatreland in general'.

That elicited this tweet from the playwright James Graham: "So sad & senseless. A theatre loved locally, well attended, but ticket refunds due to the necessary shutdown means it has no cash and no sign of a cash injection from government."

It was clear then, the bug was to blame. Fine. Except, there was one small problem. It wasn't true. Coronavirus didn't cause the multi award-winning Nuffield Southampton Theatres to go bust. It had almost nothing to do with it. The highly respected NST, which was voted Regional Theatre of the Year 2015 and had only recently moved into a brand new £30 million city-centre venue, went bust because Arts Council England (ACE) withdrew all its funding - hundreds of thousands of pounds of which was overdue - at very short notice in the middle of the lockdown.

It was a brutal, mortal blow at a time of unprecedented hardship for the theatre sector delivered by a tax-payer and lottery-funded quango whose sole purpose is to support the arts. Why, you may wonder, would it do that? Particularly as ACE had recently allocated an extra £90 million to provide short-term help to struggling arts companies it subsidises, of which £57 million remains unspent.

'Running close to break-even'

NST employees were left bemused and confused. ACE's actions would cause all 86 of them to lose their jobs when alternative theatre work is practically non-existent. Small producers and freelances have been left out of pocket, and nearly-new theatre equipment - paid for from the public purse - is being sold off to go towards the costs of the recovery for creditors and the administration process. To put the theatre and its staff in this catastrophic situation one must assume that something very, very bad had gone wrong.

Not according to Greg Palfrey. His firm was asked by the NST's board to provide an independent review of its finances in April 2020. Palfrey and his team couldn't see too much to be worried about, as is evident in Smith & Williamson's Joint Administrators' Report published 26 June 2020, external. It shows there was well over £400,000 in theatre's bank account, the business was "running close to break-even" for the financial year despite the arrival of Covid-19, and many of the teething problems of moving into the new building had been overcome. The only major problem it identified was Arts Council England, which was in arrears with its quarterly payment of around £280,000. Beyond that, Palfrey concluded no additional funding was required at that stage, and "the Company could continue on a solvent basis".

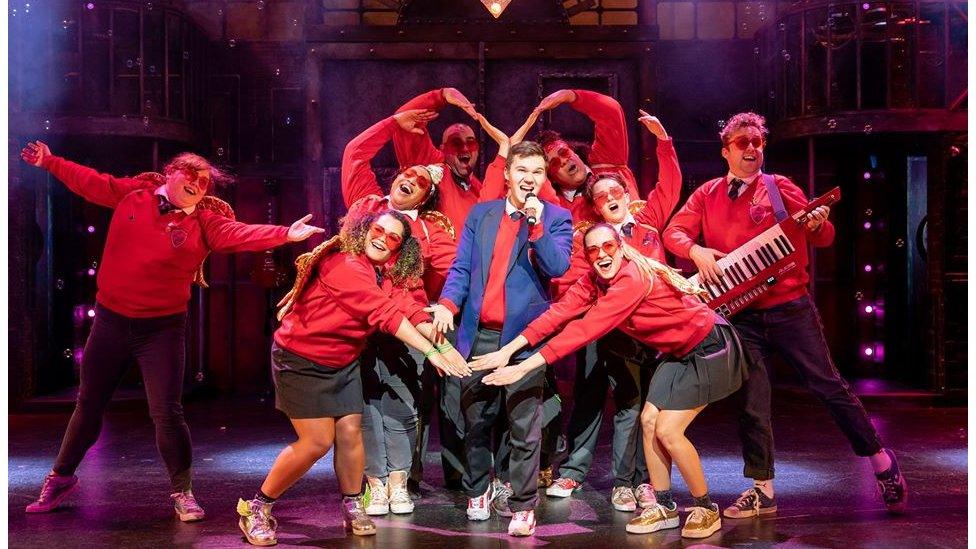

A production of David Walliams' Billionaire Boy won the theatre a prestigious award in 2018

ACE received Smith & Williamson's report in April, compared it to an earlier independent financial review that was more negative, took stock, and then pulled the plug on the theatre on 1 May. It said it had lost faith in the management and the board and had "a duty to invest public money responsibly" and couldn't "continue to invest money where it will only end up mitigating debts and does not clearly demonstrate a benefit to the public".

To many at the theatre, including senior staff, this came as a nasty surprise - although most were aware that the NST had had a bad year in 2018 when it moved into its new building. Having previously run a largely profitable enterprise (NB: profitable only because it is subsidised), which had a planned and agreed loss in 2017 due to problems with the new building, it found the first year in what was now called the NST City Theatre very challenging.

Although it had cost £30 million to build, it was not fit-for-purpose when the keys were handed over by the building's owners Southampton City Council, who had contributed around £20 million towards its creation, with another £7.2 million coming from ACE. The new theatre was on the second floor above a Nando's, which would have been fine if the customer lift worked, but it didn't, making the theatre inaccessible to many people, and off-putting for potential clients who might want to hire the space for events. The goods lift at the back didn't work either, causing costly and cumbersome scenery removals in and out of the building. Added to which, the café franchisee, who was an important part of the original business plan, pulled out.

Such teething problems are not unusual in new buildings, but the difficulties didn't stop there. A production of Peter Morgan's The Audience didn't do as well at the box office as had been hoped, and production costs nearly doubled as Sam Hodges, the long-standing, award-wining Artistic Director and CEO, got to grips with producing shows for the new theatre as well as the original much-loved 1960s Nuffield Campus Theatre at the University of Southampton.

The inaugural show at the new venue was The Shadow Factory - which explored the history of "secret" Spitfire factories

By the end of its financial year, NST had spent all its reserves (a crucial buffer that all theatres need to maintain in order to satisfy the accountants) and filed a £507,000 loss. This, not unreasonably, gave ACE significant cause for concern. It could, though, perhaps find some comfort knowing it was partly caused by issues with the new building (NST lost £107,000 the previous year, but this was planned for and agreed by all parties) and it backed Hodges and his team, who had a track-record of running a surplus budget.

There were other areas of reassurance, too. NST was delivering an artistic programme that was respected nationally and popular with local theatre-goers (box office records were broken in 2018 and 2019), critics (Billionaire Boy: The Musical was the 2019 UK Theatre winner Best Show for Children and Young People), and ACE. It was also doing good work in the community and nurturing local theatre-makers such as Zoie Logic, about whom Darren Henley, the CEO of ACE, enthusiastically tweeted on 27 September 2019: "Inspirational afternoon with brilliant ACE-supported @zoielogic in Southampton".

The financial difficulties of 2018 were bad but not wholly exceptional for a producing theatre establishing a new business model. It was, for the first time in its history running two venues: The old campus theatre and the new city centre space. ACE had supported the expansion by nearly doubling its annual grant to the NST from £553,000 to £974,000 in 2015. The Arts Council was also used to helping theatre companies when they encountered choppy waters. In the recent past both the English National Opera and Liverpool Everyman Theatre were given significant support in their times of financial trouble, where artistic ambition had exceeded financial realities.

In crisis?

ACE didn't pull the rug from under either of those two institutions, both of which it helped through a period of re-building management teams and board members, even though the two organisations were in breach of the terms and conditions of their funding agreement in relation to financial viability. So why did the Arts Council go to the apocalyptic lengths of effectively bankrupting the NST citing a loss faith in a management team led by someone it had repeatedly backed and a board with a new Chair? The answer is not clear.

ACE said the theatre was "in crisis for some time", but published accounts and the responses to its artistic programme suggest a difficult year in 2018 rather than historic mismanagement. ACE asserts the NST didn't offer an alternative business plan. The NST disputes this, saying that there were several iterations of a business plan put forward - and claim they were told by ACE, as recently as autumn 2019, that the business was going in the right direction.

ACE says the NST was going to lose over £100,000 in the financial year to March 2020, when, in fact, it lost £17,000. ACE said it asked for new management accounts that didn't materialise, the NST said they provided timely and comprehensive management accounts. ACE called for organisational review, NST says Hodges offered to step aside as CEO and leave if necessary. ACE said it had lost faith in the board, NST says the board had a new Chair who only started in June 2019 and hadn't been given the time to refresh and settle a new non-executive team. ACE says an Executive Director hired in 2019 left citing Hodges as impossible to work with. NST points out that the Executive Director never took up her full-time post, and when ACE was asked for evidence of the accusation it could not provide any beyond attributing the comment to a phone call.

Sam Hodges was appointed artistic director in 2013.

The list of claims and counter-claims goes on. Ultimately these things are subjective: They are about belief and projecting into the future. If ACE thought it was throwing good money after bad, it was within its rights to withdraw the remaining £1.9 million that it had committed to the NST (the money has been ring-fenced by ACE for future arts activity in Southampton). But questions remain.

Why did ACE allow the perception to persist that the NST went bust due to Covid-19 when it knew perfectly well that wasn't the case? Why could it not find a way to support a management that had long delivered a respected artistic programme? And, why not allow the NST the same time and space afforded to the Liverpool Everyman and English National Opera to put its house in order? Note: This would have required the theatre to opt out of being an ACE "National Portfolio Organisation, external", while the quango helped the business back onto its feet. The NST Board began this process by applying to leave the NPO, a request that was accepted by ACE on condition of an independent review of its finances. The review happened, the Board didn't agree with some of its assumptions (EG that the NST would lose over £100,000 in the financial year) and invited Smith & Williamson to conduct a review, which concluded the business was in a fit state to continue to operate as a "going concern". ACE took a different view, and deemed the theatre's position as "irrecoverable".

Were there other factors that might have influenced ACE's decision? Possibly. ACE increased its funding to the NST in 2015 because it was expanding to run two venues. But last year, the University of Southampton, which owns the Sir Basil Spence-designed Nuffield Theatre Campus, gave notice that it was taking back the building's lease. This meant that from April 2020 - a month before ACE withdrew funding - the NST would only be running one venue: The new city centre theatre above Nando's. Might ACE have been tempted to ask for half its money back? Yes. Did it? No. Are those theatre operators to whom the Arts Council is currently talking about taking over the space being offered the full amount in subsidy or the reduced sum? That will become apparent in due course.

Actress Celia Imrie donated money to try to save the theatre operator after it went into administration.

The decision by the University of Southampton to take back its lease changed the ecology of the theatre scene in the city, which includes the much bigger Mayflower Theatre. Did ACE see an opportunity to consolidate the one-venue NST into a "Southampton Theatres" offer, which might involve a partnership with the commercial Mayflower, perhaps alongside the university's refurbished Nuffield Campus Theatre? Maybe that would allow it to invest its £1.9 million differently, focussing on up-and-coming theatre groups like Zoie Logic? This is all speculation, but it might offer a rationale as to why ACE and Southampton City Council (SCC) chose to rebuff three offers to buy the existing NST in early July, and thereby save it from going bust and potentially its staff from losing their jobs. Smith & Williamson had put forward what it considered to be three serious bidders to ACE and SCC, which had been whittled down from more than 30 potentially interested parties, but all were sent packing for not fulfilling their criteria. A disappointed Greg Palfrey said "we did everything we could to keep NST alive" but now he had to go into immediate closure and asset sale mode as from 2 July. That meant the staff had to go, leading to this tweet from James Graham:

"Southampton Nuffield Theatre is closing for good. 60 yrs of investment, training & serving its community. All profitable in normal times, just needed shortfall funding while closed & it didn't come in time. So sorry to the 86 made redundant, & the locals who loved their theatre".

Artists performed at the launch event in front of the £30m complex in 2018.

The truth is, there was the money, and that's even before taking into consideration the £57 million of emergency funding not used by ACE. The staff lost their jobs because ACE decided to stop funding the theatre. Maybe it was a pre-determined decision, maybe it will be for the best, maybe it was the right thing to do at the right time. Maybe. But when you look at the data: The published accounts, the published report by Smith & Williamson, the artistic record of Hodges and his team, it is understandable that the people who worked at the NST question why ACE took such a drastic step, delivering a fatal blow to the theatre and their livelihoods during a global pandemic before all other avenues had been fully exhausted, such as the NST coming out of the NPO, or a working towards a change in management. Was there really no other option?

The good news is the Arts Council and Southampton City Council are committed to keeping the new building as a theatre. They are currently in discussions with potential operators with an announcement expected very soon. Sadly, it will be too late for the 86 people Smith & Williamson are making redundant in order to bring the final curtain down on the decades old Nuffield Southampton Theatres Trust.

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published2 July 2020

- Published16 February 2018