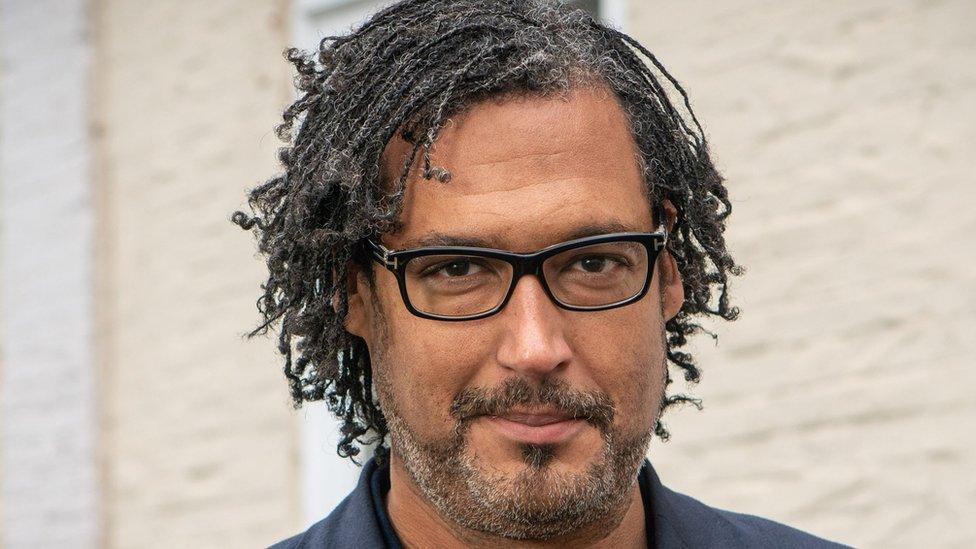

David Olusoga: 'TV industry left me crushed'

- Published

TV presenter David Olusoga has told the Edinburgh TV Festival his career had sometimes left him feeling "crushed, isolated," and "disempowered".

The historian and producer said he wanted to talk about his experiences as a black person working in TV "in the spirit of Black Lives Matter".

He said sometimes he felt working in TV was "the best job in the world".

But he added the industry's "culture" had also led him to seek medical treatment for clinical depression.

"I have been given amazing opportunities, but I've also been patronised and marginalised," he said in his MacTaggart Lecture.

"In the spirit of Black Lives Matters, in the spirit of an age in which millions of people have come to recognise that silence on these issues is a form of complicity, I am going to say what I really think about race, racism and our industry," he continued. "And I'll discover if, at the end of it, I still have a career."

He warned broadcasters they risk fading into insignificance if they don't better represent "marginalised" people.

"I've been in high demand, but I've also been on the scrap heap. I've felt inspired, and convinced that our job - making TV and telling stories - is the best job in the world.

"But at other times I've been so crushed by my experiences, so isolated and disempowered by the culture that exists within our industry, that I have had to seek medical treatment for clinical depression."

He added: "I've come close to leaving this industry on several occasions. And I know many black and brown people who have similar stories to tell."

'TV's lost generation'

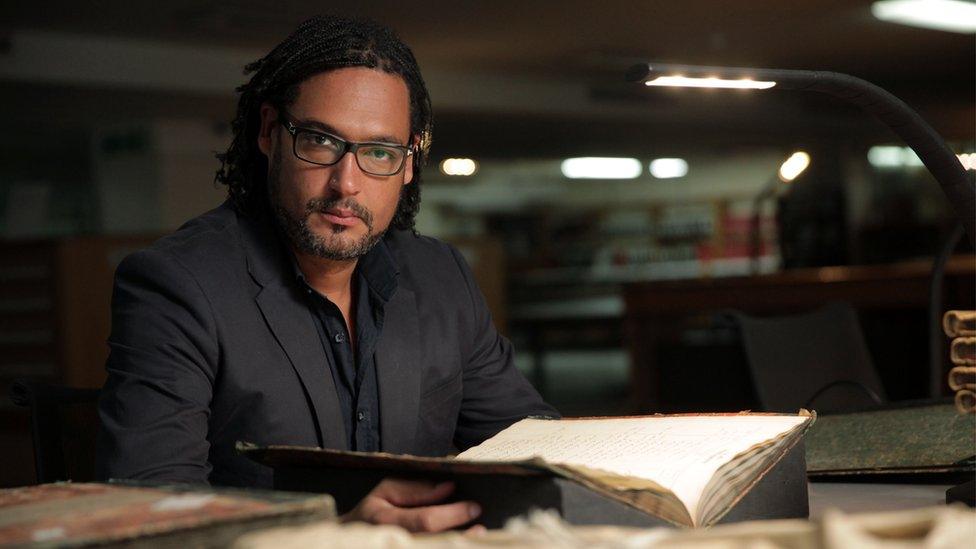

Olusoga, who won a Bafta for his BBC documentary, Britain's Forgotten Slave Owners, made the comments while giving his keynote MacTaggart Lecture speech at the online event.

Looking back on his career, the broadcaster and writer said he viewed himself as a "survivor", rather than "a success story".

"I am one of the last men standing of TV's lost generation," said Olusoga, who has also contributed to The One Show and The Guardian.

"The generation of black and brown people who entered this industry 15, 20, 25 years ago with high hopes.

"I'm a survivor of a culture within TV that failed that generation. I'm here because a handful of people used their power and their privilege to help me."

David Olusoga won a Bafta Award for Britain's Forgotten Slave Owners

In 2016, Directors UK reported that 2.22% of TV programmes were made by black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) directors; who made up 3.6% of their data-set.

The Film and TV Charity recently reported to the government that 73% of BAME production talent had considering leaving the TV industry.

Olusoga noted how he'd attended a session at the Edinburgh TV festival 12 years ago on the topic of when exactly we might see the first black controller of a major network.

Over a decade on, he stressed, the question remains.

Oxford and Cambridge

"For as long as I've been in this industry we collectively have been aware that the people who make and commission the UK's television programmes do not look like the population at large - our audience," he said.

He referred to a story when he was filming on a reconstructed slave plantation that had been built in Jamaica for a drama-documentary.

"As we were filming in a remote location we set up our own catering and on the first day cast crew and extras queued up for lunch. But without informing me it had been decided that the actors and the crew were to eat first, the extras would get their lunch afterwards. Standard procedure perhaps, but the unintentional effect was that white people ate first and black people only after they had finished."

He said what he found " most shocking... was that my white colleagues - good, decent, creative people - genuinely could not see the problem, a problem that the black actors and the black extras had no problem seeing."

He also spoke about class privilege.

"What I learnt in my early years in TV is that there were parts of the industry in which diversity meant making sure that there was a fair balance of people from Oxford and Cambridge."

'Silence on these issues is a form of complicity'

The broadcaster and writer also stressed that retaining TV talent and workers from non-white backgrounds was still a major issue, saying: "We had them, we lost them". He referred to the mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees. "When I asked Marvin Rees why he had finally given up and left the industry this is what he said, 'The truth is, the BBC just wore me down with hopelessness.'"

He underlined how the events of 2020, including the Black Lives Matters protests in the wake of the death of George Floyd; and the spread of Covid-19 had "made manifest and obvious some of the oldest and deepest inequalities in our society".

"The generation that is leading this global shift in consciousness and for whom these principles are sacred, is also the generation that our industry is at risk of losing," he said.

But he did feel there was hope for change this time around: "So much has been promised that there is reason to hope that this really is a moment of change for our industry, rather than a false dawn - and we've had a number of those.

"There is, I honestly believe, real reason to be hopeful. This time it does feel different."

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published22 June 2020