No such thing as the internet

- Published

This is the age of the tech cold war. It is America v China

Six decades after the Advanced Research Projects Agency of America's Defence Department (ARPA) began funding research on time-sharing between computers, which led eventually to the revolutionary technology we call the internet, the time has come to drop the definite article.

Just as the claim that politicians are merely following "the science" when it comes to the pandemic is an attempt to create the illusion of consensus, so talk of "the internet" now refers to a phantom.

Today there is no such thing as the internet. There are internets - plural - with different, indeed rival, systems erupting in many places, but two dominant kingdoms: an American (OK, Californian) internet, and a Chinese one. The latter, being the product of the Communist Party, has a plan to win the future. The former, being a collection of disparate and competing companies, does not.

After the splinternet

Over the past year, I have been thinking and writing about the fact that one of the great questions societies need to ask themselves today is: What kind of internet do you want?

As I mentioned in that earlier blog, the idea of a splinternet has emerged, and with it the claim that there are two other main internets aside from the Californian and Chinese ones: a libertarian free-for-all of the kind envisioned by an earlier generation of digital pioneers; and also a more regulated, European one. That makes four in total.

Now I'm starting to think this idea of "four kingdoms", external is also rather damaging, in a couple of ways.

First, it overlooks the fact that there are potentially - not yet, but potentially - as many internets as there are nation states with laws.

When, earlier this year, TikTok and 58 other Chinese-owned apps were banned in India, the world's largest democracy slipped into a category all of its own, and certainly not covered by those four kingdoms. India-without-TikTok wasn't a Californian, European, or libertarian internet. And neither, obviously, was it a Chinese one. It was an Indian internet.

When, earlier this year, TikTok was banned in Indonesia, the ban only lasted for a few days, and was initially justified on different grounds from the ban in India.

India banned the Chinese apps mainly because of how they use data. Indonesia banned TikTok - though not many of the other apps banned by India - because they were thought to be blasphemous, and promote pornography, in the world's largest Islamic population.

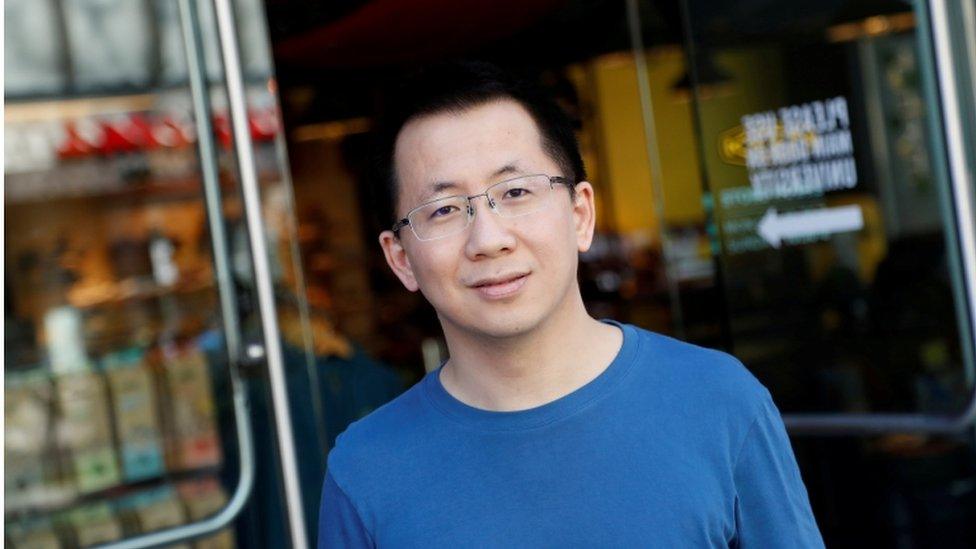

Zhang Yiming, founder and global CEO of ByteDance, the Chinese company which operates TikTok

It's not particularly useful to understand India or Indonesia's decision through the paradigm of the four kingdoms. These countries came to their own, unique decision for their own, unique reasons.

As more and more countries do this, it will be instructive to think not of one internet, but many internets, each with their own specifications attuned to local custom, practice and freedom of speech. This will help, for instance, businesses planning their operations in different territories. And it will help us all to grasp why people in different parts of the world have such wholly different responses to, and understandings of, the same event.

For instance, what if, in the maelstrom of the US presidential election, Beijing invades Taiwan?

This may not be as fanciful as you think., external Should it happen, those in the West who are horrified need to remain very alert to the fact that, in China, citizens will be getting a very, very different version of events.

Which brings us to the second shortcoming of the splinternet theory of four kingdoms. It's true that, the internet is splitting into as many territories as there are nation states. Yet at the same time it is true that one paradigm matters much, much more than any other.

Tech Cold War

This is the age of the Tech Cold War. It is America v China.

All the stories you have seen this year about President Trump clamping down on TikTok (and demanding its sale to an American owner), or about Huawei, are best understood through this prism.

America and China are vying for technological supremacy. Cyberspace is the battlefield.

When President Trump demanded that TikTok's US operations be sold to an American company, and that the US Treasury take a cut, there was a predictable outcry from those who saw this as an appalling incursion into the economic liberty which did so much to create American hegemony.

And yet, intriguingly, America's leader was merely borrowing from the Chinese playbook. In China, YouTube, WhatsApp and many other platforms are of course banned. The internet is policed, and is itself used as a policing surveillance tool by the Communist Party.

Fans of democracy everywhere have to ask themselves: why shouldn't nation states demand control of the internet within their borders? And if there is a trade-off between economic liberty and national security, why should the former automatically win?

The US President Donald Trump meeting China's President Xi Jinping at the G20 meeting in Japan in 2019

China is one of those very, very rare subjects which commands bipartisan support in the US. A Biden administration would see technology as a foreign policy issue, and China as a tech policy challenge.

They may be encouraged in this, by the way, by Sir Nick Clegg of Facebook. Biden is one of the US politicians Sir Nick knows best, since they were both de facto deputy national leaders at the same time, have a similar political heritage, and used to talk regularly.

Through its extraordinary investment programmes in central Asia and Africa, China is already making a play for good favour from the people of those regions. Many of those people are among the three billion who still don't have access to the internet.

China has a plan to ensure that the internet they do have access to is a Chinese one: a highly-controlled digital service in which data is ultimately controlled by the Communist Party. If the US has a plan as coherent and well invested in, it's been remarkably quiet about that.

One of the many reasons democracies have made such a mess of regulating the internet, and have struggled to spread its benefits while reducing its harms, is the astonishing lack of basic knowledge among policy-makers.

Alerting them to the fact that there is no such thing as "the internet" any more, if ever there was, might give them a better chance of competing in the Tech Cold War that is upon us, and in which China has hitherto been more strategic.

If you're interested in issues such as these, please follow me on Twitter, external or Facebook, external; and also please subscribe to The Media Show podcast, external from Radio 4.