Uncle Vanya: Will Gompertz reviews Chekhov's play on film ★★★★★

- Published

There are not many upsides to the wrecking ball that is the current pandemic. So many lives and livelihoods have been lost it is often difficult to see beyond the devastation. It's been a relentless grind of bad news heaped upon bad news. Good news has become as elusive as waiting for the apocryphal bus: you hang around for ages and then two come along at once, only for you to realise you've forgotten your mandatory mask.

It is all a bit dispiriting.

Not unlike one of those Chekhov plays in which everyone is miserable to differing degrees. "I am at least as unhappy as you" says Sonya to Uncle Vanya in a bid to out-glum the man who brought her up on a down-at-heel country estate in Russia.

I know this, not because I am able to quote Russian 19th Century playwrights at will, but because I've just watched a filmed version of the critically-lauded Uncle Vanya theatre production that was abruptly halted in March due to Covid-19. Having done so, I am delighted to report that I have some good news…

It is excellent.

Better still, you can actually see it (in cinemas later this month, or on the BBC later this year), which you probably wouldn't have been able to do had it completed its West End run at The Harold Pinter Theatre where tickets were selling faster than second homes in New Zealand.

Ian Rickson's acclaimed production of Conor McPherson's adaptation of Uncle Vanya at the Harold Pinter Theatre, was cut short by Covid-19

All but one of the original theatre cast are in the cinema production, which was filmed at the mothballed Harold Pinter Theatre, where Rae Smith's wonderfully evocated faded-glory set remained intact and in-situ.

Filming stage plays for the screen is not straightforward. It is easy to fall into the trap of having the worst of both worlds: no atmosphere, and no detail. That is emphatically not the case in this instance.

Ross MacGibbon has skilfully reinterpreted Ian Rickson's highly praised stage direction with the deployment of six cameras, a first-class sound mix, and superb editing (apart from a couple of rushed cutaways).

It is not so much a film of a play, but a play on film - not unlike Denzel Washington's movie version of August Wilson's Fences, or Roman Polanski's celluloid remake of Yasmina Reza's God of Carnage.

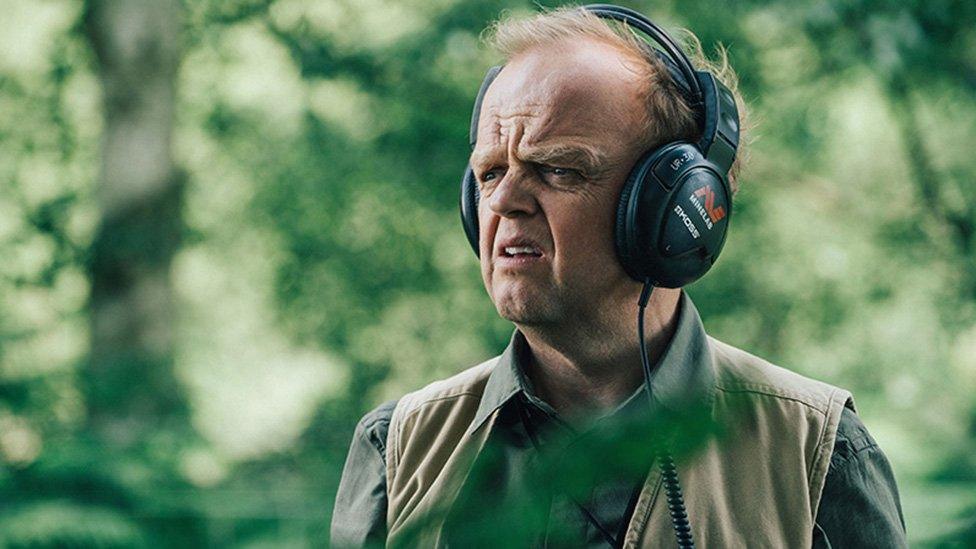

Toby Jones reprises his role as the eponymous Uncle Vanya in what is a lively new adaptation by Conor McPherson ("wanging" hardly being a Chekhovian word). Jones, who is perhaps best known for playing Lance - the downbeat, oddball treasure hunter in Detectorists - gives us a downbeat, oddball Uncle Vanya who has taken to drink to numb the pain of a wasted life.

Toby Jones gives a deeply moving performance in the title role, Uncle Vanya

Toby Jones played Lance, who has a passion for metal detecting, in the popular comedy series, Detectorists

He despises his brother-in-law Professor Serebryakov (an appropriately haughty Roger Allam), whom he once revered but now recognises as a fraud with as much substance as a "soap bubble".

To make matters worse, Serebryakov has retired and come to live in the vast but dilapidated country house Vanya has struggled to keep going for the past 25 years, with the help of his good-natured niece Sonya, played with aplomb by the very impressive Aimee Lou Wood (Sex Education).

(From L-R) Anna Calder-Marshall as Nana, Aimee Lou Wood as Sonya, Roger Allam as Professor Serebryakov and Rosalind Eleazar as Yelena

To make matters worse still, Serebryakov's much younger second wife, Yelena (the talented Rosalind Eleazar), is the love of Vanya's life. Unfortunately, the feeling is not mutual...

Yelena: Vanya, you know what happens every time you talk to me about love?

Vanya: No, tell me

Yelena: I feel completely dead

Vanya: Well, that's not good.

Jones is an entertaining presence throughout, lightening the mood when needed with his abundant comic gifts, or dampening it with a trademark pitiful look or snide remark. He is the star around whom all others orbit, not least the strung-out Doctor Astrov (Richard Armitage), who shares Vanya's love of booze and Yelena.

The scene in which Astrov shows Yelena his painted maps of the local landscape, pointing out a fast-approaching ecological calamity, is as good as any you will see on film or on stage. The pent-up passion, their shared hopelessness, the marginal misunderstandings, all combine to create a desperately sad, sensual atmosphere, which both actors play with notable deftness.

Richard Armitage as the romantic idealist Doctor Astrov with Rosalind Eleazar as the sensuous Yelena

Uncle Vanya belongs to a different time and a different place, but like all good plays it lives on and resonates for each epoch.

Chekhov's concerns for the environment, for over-worked and underappreciated medics, for all those who feel trapped by their lives, feel wholly relevant. The astute and sometimes comic way in which these themes are explored, along with other timeless concerns such as unrequited love, boredom and unfulfilled potential, gives Uncle Vanya its power and purpose.

It is a great work of art.

Admittedly, it probably won't leave you beaming from ear-to-ear, but it will touch your heart and soul.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz:

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external