Artemisia Gentileschi: Will Gompertz reviews her show at the National Gallery ★★★★★

- Published

There is an art to exhibiting art. Good curators are more than specialist academics with arcane knowledge they share from time to time with us in an exhibition. Good curators are storytellers with a sense of theatre and occasion. Good curators are impresarios.

The National Gallery in London has more than its fair share of good curators, not least Gabriele Finaldi, the institution's boss. He is a specialist in Renaissance and Baroque art with an international reputation, which must be an additional pressure if you happen to be a rank-and-file National Gallery curator putting on a show of Renaissance and Baroque art.

When I put this to Letizia Treves, the curator of its newly opened Artemisia Gentileschi exhibition, she smiled graciously. We left it at that. No need to elaborate. Anyway, her show does the talking for her.

It starts well.

The first painting you see sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition. It is not only big, biblical and Baroque, but also has a subject matter that provides important autobiographical detail about Gentileschi, who painted Susannah and the Elders (1610) when she was a 17-year-old apprentice working in her father's studio in Rome.

It depicts the Old Testament story of the virtuous Susannah - who is trying to have a private bath in a fountain - being harassed by two lecherous men. They tell her that if she refuses to succumb to their advances they will accuse her of adultery, a sin punishable by death.

Susannah and the Elders, 1610

It's a remarkably accomplished picture for one so young, completed under the tutelage of her father, Orazio, who might also have had a hand in its creation. The modelling of the nude body, the colour-mixing used in the rendering of the garments, and the play of shadows are all techniques she learned from her father.

But the emotion and palpable menace the painting transmits are pure Artemisia.

For her, it was personal.

The teenage artist was a young woman operating in a man's world.

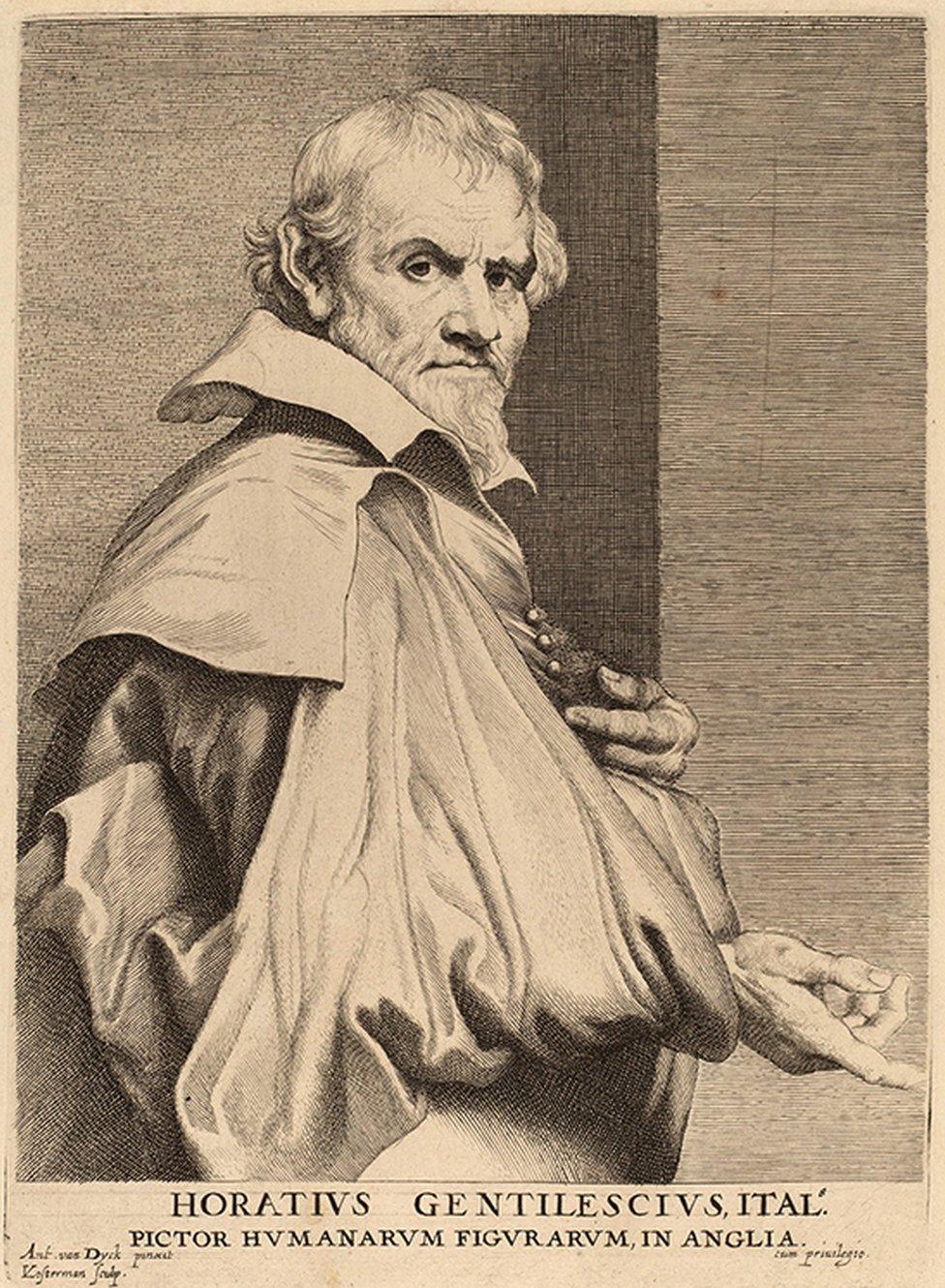

The artist, Orazio Gentileschi was Artemisia's father and teacher

Unwanted and uninvited sexual advances were not unknown to her. She could relate to Susannah's ordeal. And more. Around the time she was working on this painting, her father began a collaboration with an artist called Agostino Tassi, who aggressively pursued Artemisia.

She rebuffed him.

He attacked her, she fought back.

But he was too strong.

Tassi stood trial for her rape in 1612, the transcript from which is shown in the exhibition. He was convicted, but not before the court had tortured Artemisia by crushing her fingers until she screamed. They wanted to be sure she was telling the truth.

"It is true! It is true! It is true!" she exclaimed through the pain.

It is a traumatic experience that has come to define Artemisia Gentileschi as an artist and a historical figure. Given what she produced next, you can see why.

On the right-hand wall in the second room of the exhibition hang two huge paintings of the same Old Testament story, Judith Beheading Holofernes. Made by Gentileschi between 1612-14, they do not spare any of the gory details. Judith uses her left hand to get a decent grip on Holofernes's beard, while in her right is the sword with which she decapitates the Assyrian general. Blood gushes as the artist captures the most horrific moment in this most horrific act.

It is a piece of revenge art, according to many commentators.

And so it might be. But to limit it and the woman who created the picture to such a reductive reading is to underplay, and possibly miss altogether, her significance as a major figure in the history of art.

Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1612-13

Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1613-14

First and foremost, Gentileschi was an exceptional artist, as these two paintings demonstrate. Her mastery of composition, colour and line are first class. The modelling of the three figures is highly sophisticated, as is her use of chiaroscuro (exaggerated contrast between light and shade). Added to this is the drama and atmosphere she conveys in pictures that present the female protagonist in a new light: independent, powerful and determined.

Artemisia Gentileschi was a uniquely gifted artist who should be considered among the all-time greatest painters, regardless of her back story.

True, she might well have pictured Tassi in her mind as the blade plunged into one of the many male characters in her shock-and-awe paintings. But that was not why she made them. They were commissions. Such scenes were all the rage in 17th Century Italy, where Baroque art - as defined by Caravaggio, with its dramatic lighting and narrative theatricality - lent itself to the spectacular.

There is a cinematic quality to it that has influenced filmmakers from Orson Welles to Martin Scorsese. We like thrillers and horror movies. They liked thrillers and horror pictures.

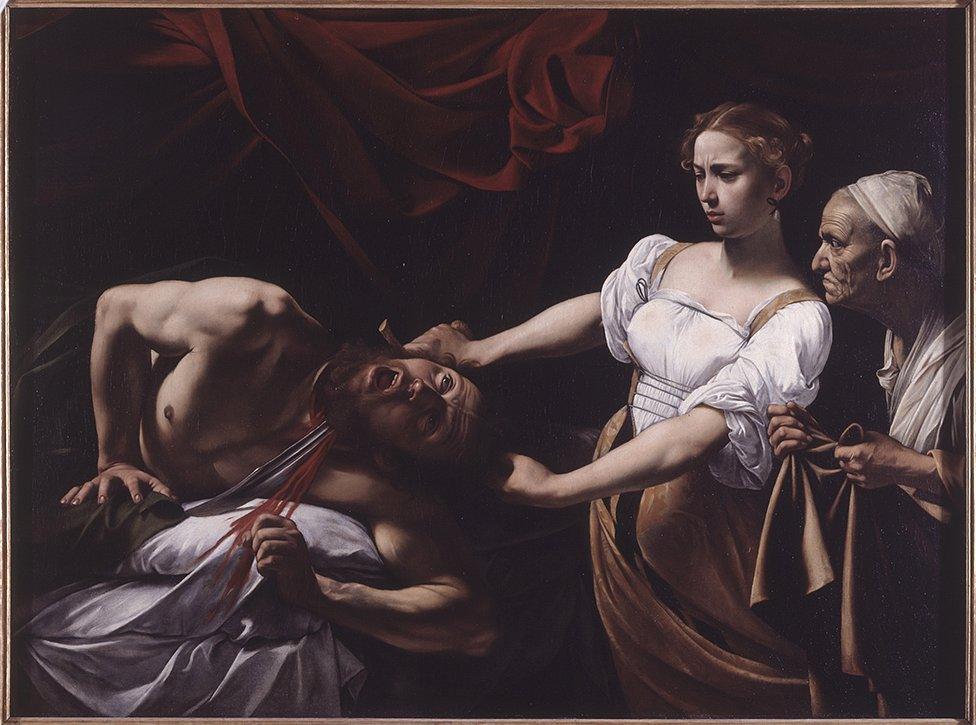

Orazio Gentileschi learned his methods from Caravaggio, who painted his version of Judith Beheading Holofernes in 1599. It is a technically better picture than the 20-year-old Artemisia's, but it doesn't have the same graphic intensity, and his Judith looks timid and a bit weedy.

His is a pre-watershed picture. Hers is most definitely post-watershed.

Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1599, by Caravaggio

Not every painting she produced was a winner.

There are 29 in the National Gallery show, a few of which are not top notch. But even when she makes a mistake, the outcome is compelling. In 1623 she started work on another Judith picture, this time skulking away in the aftermath of her murderous act in Judith and her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes (1623-5).

It has all the hallmarks of the Italian Baroque: a simple design, a limited number of figures who appear near the front of the picture plane, blocks of rich yellows, reds and blues - and, of course, the single light source creating a scene full of melodrama.

Judith and her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes, 1623-5

The trouble is that the single light source in this instance - a candle near Judith's upper arm - is in the wrong place. It is too far behind Judith, who has her left hand held out catching the light that is clearly behind it, which is not possible. The mistake is compounded by a poorly painted shadow covering much of Judith's face, which is also not possible. It's a splodge and a botch.

And yet. Who cares?

The fabrics are beautifully painted, Judith's hand is wonderfully rendered, and the composition of the scene is a success.

The exhibition ends in London, which is where Orazio had moved to work in the court of Charles I. It is here that we are told Artemisia produced one of her finest paintings.

It is a self-portrait called the Allegory of Painting (1638-9). She had used herself as a subject on numerous occasions, but usually in the guise of someone else, as is the case with the National Gallery's recently acquired Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1615-17).

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura), 1638-39

Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1615-17

There is no hiding behind another character in this grand finale, show-stopping self-portrait, in which we see her at work (made possibly with the use of a mirror) dressed in a splendid green silk dress with a lace trim. She looks younger than a woman in her mid 40s (her age when in London), which has led some to question whether she made this painting earlier. But it doesn't really matter.

The painting matters. And it's wonderful.

It is an extraordinary achievement by an extraordinary artist.

It is a good way to end a good show by a good curator.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz:

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external

- Published22 December 2018