Ted Hughes & Seamus Heaney: Will Gompertz reports on a previously hidden treasure trove

- Published

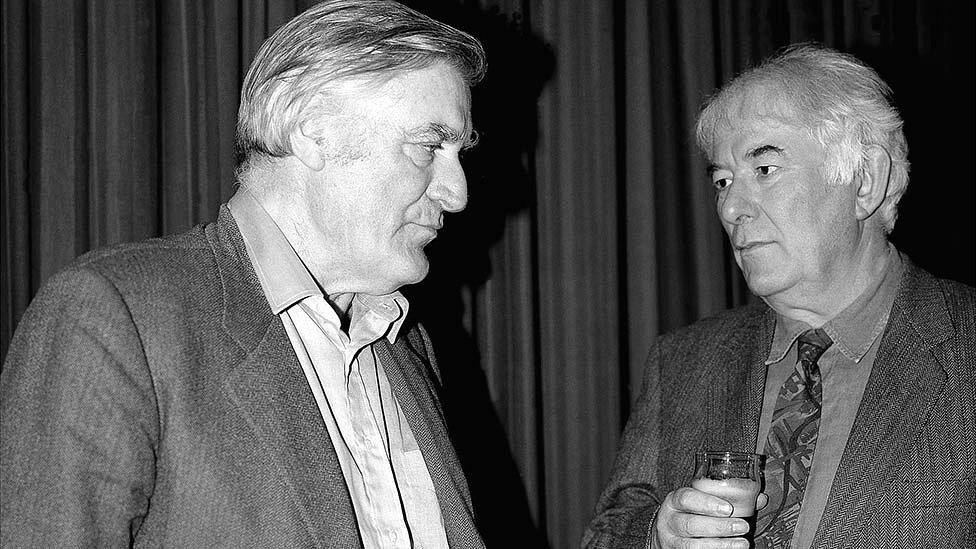

Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney enjoying each other's company

A recently discovered archive of previously unseen letters, drawings and poems by Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney - two of the great post-war poets - has been acquired by Pembroke College, Cambridge, which will put them on public display. Will Gompertz spoke to the man behind the find.

It was May 2013, not that the month or the year meant a great deal to Barrie Cooke. Dementia was robbing the 81-year old artist of his quick wit and sharp mind. Although he was still painting, the present was a mystery to him, the past an evaporating memory.

Days came and went.

On this particular May morning he was sitting - as he did every day - in an unprepossessing armchair in an assisted-living facility in County Kilkenny, Ireland - a country that'd been home to the Cheshire-born painter since the mid-1950s.

Opposite him was Mark Wormald, an energetic English lecturer from Cambridge University. The two had met a year earlier at Wormald's behest when Barrie was in better shape and still living in his own home in County Sligo. The 54-year academic had been in the British Library trawling through Ted Hughes's fishing diaries when he came across an entry containing Barrie's name. He was curious and read on.

Turned out Barrie and Ted went way back. They'd been close friends for decades, bound by a passion for poetry and fishing.

Ted Hughes and his friend, the artist Barrie Cooke pike fishing in Ireland, 1978-9

Wormald liked poetry and fishing, too. A field trip beckoned for the Fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge, the late Poet Laureate's alma mater.

He packed his rod and tackle and headed west.

On arrival, Barrie confirmed Ted and he had indeed been long-standing friends, as was evident from the row of Hughes's published poetry on the bookshelf. But it didn't explain the books jammed in on the shelf below, all of which bore another author's name.

Seamus Heaney, the Irish poet and Nobel Laureate, was also an old pal of Barrie's. He had been for nearly as long as Ted - they were all brothers in art. Theirs was a triangular friendship built around a deep romantic connection with Ireland, its rivers, lakes and bogs, and angling.

Seamus Heaney at a turf bog in Bellaghy in Northern Ireland, 1986

It was Barrie who tried to get Heaney into fishing. He was with him in Belfast when Seamus purchased his first rod and reel, only to leave it on the roof of the car after a fishing expedition.

Typical Seamus.

Wormald was astonished to hear about this decades-long kinship between a rural artist and two of the world's most famous poets.

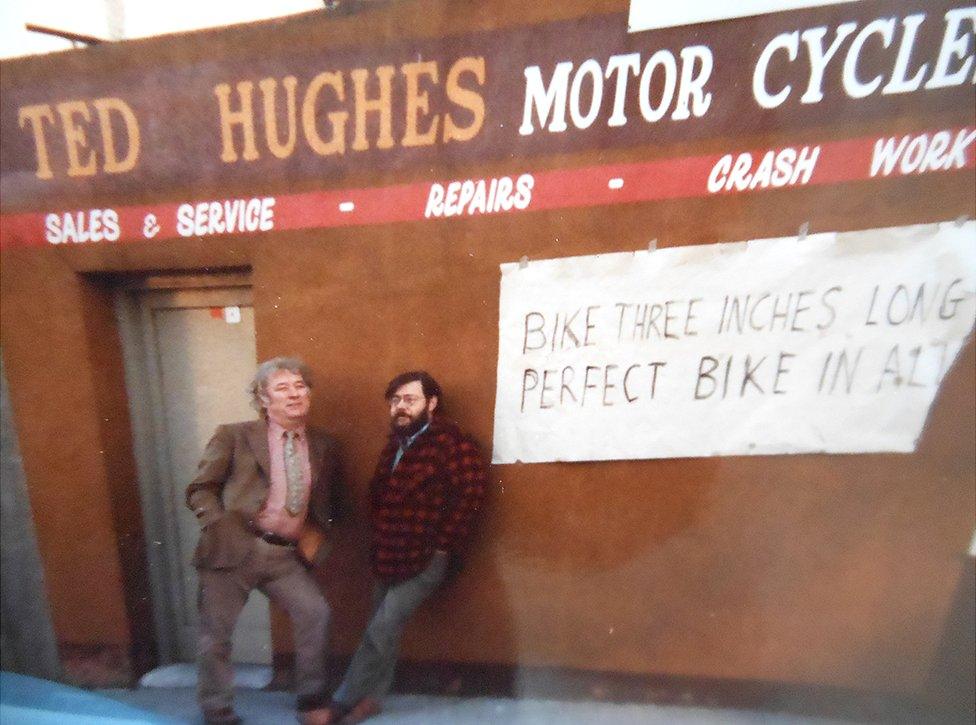

Seamus Heaney and Barrie Cooke posing under a sign for Ted Hughes motorcycles in Dublin, 1985 (Pembroke College acquisition)

When he returned a year later in May 2013, the artist was fragile and frail.

The academic's hope of hearing more stories that might enhance his understanding of Hughes and Heaney faded. He picked up a transcription of an old fishing diary Ted kept (the original is in the British Library), and read out a 200-line verse entry Hughes had made in March 1980.

It told the story of Ted catching his first Irish salmon and concluded with the line:

"It's the most beautiful fish I've ever seen", said Barrie

At once Barrie declared to Mark: "I did say that. And it was!" And then, out of the blue, "would you like to see the letters?".

"Err, yes" said the Cambridge don.

The old man pulled back a shabby curtain behind which was a battered, wooden leek box. He motioned for it to be brought to him. Inside were a stack of papers, photographs, drawings, notebooks and letters from Ted and Seamus and many other poets besides.

Watercolour portrait of Seamus Heaney by Barrie Cooke, about 1980 (Pembroke College acquisition)

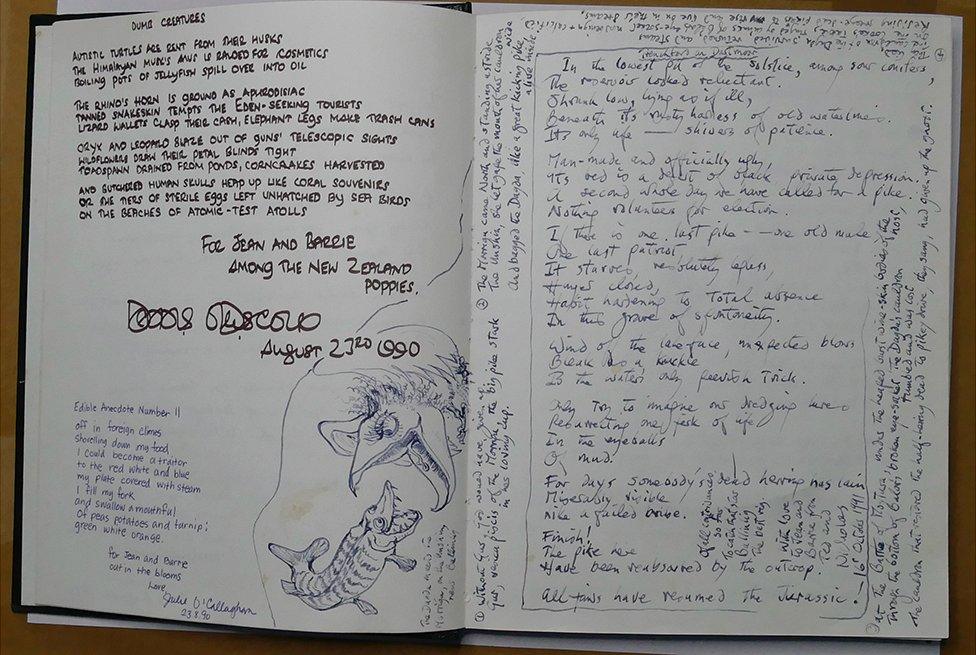

Mark delved in the box and picked out a handful of letters from the two poets. A few had doodles in the margins, several contained lines of poetry. Poetry the academic from Pembroke College, a specialist in the works of both men, had never seen before. He sat back and considered the tatty box to his side. He had gone to Ireland expecting a gentle chat and little more, and had unwittingly stumbled upon an extraordinary treasure trove.

There was more of the same back at Barrie's studio in County Sligo. In all around 85 poems by Heaney, including multiple drafts that gave an insight into how the poet crafted his work. The relationship he had with Cooke went beyond asking him to illustrate some of his compositions (Bog Poems in 1975) but also to act as a sounding board for his writing.

Barrie Cooke's watercolour and ink illustration for Seamus Heaney's Bog Poems, 1975 (Pembroke College acquisition)

The letters and notes reveal how Heaney developed some of his creations by going through a shared, iterative process, an example of which can be seen from a short postscript entry he made in Barrie's visitor's book in August 1990. It reads:

P.S. [but nb on previous page]

And then years later, they appeared to me

Running by themselves in a moonlit field—

The hands of the freckled man who kept the ferret.

These lines, in loving memory of his father who had died in 1986, were hardly an afterthought - they ended up evolving into the succinct but beautiful An August Night, published in Seeing Things (1991):

His hands were warm and small and knowledgeable.

When I saw them again last night, they were two ferrets,

Playing all by themselves in a moonlit field.

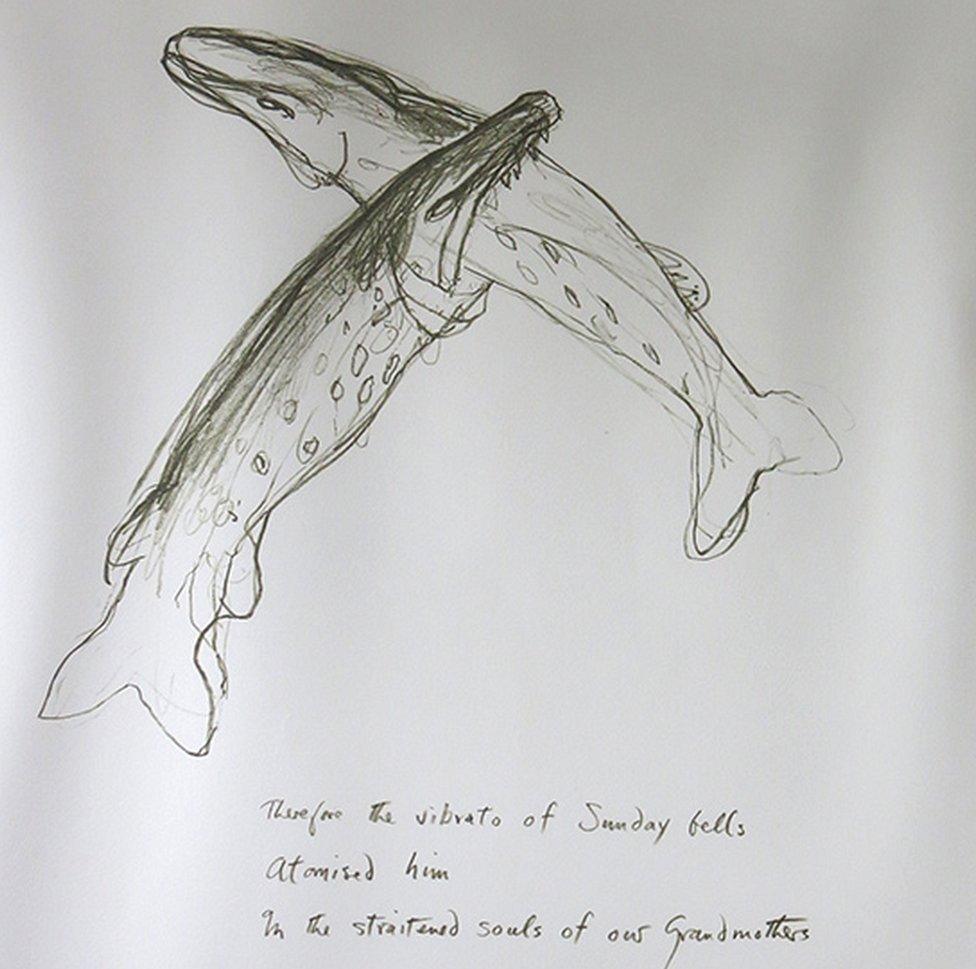

A similar to and fro of words and images occurred between Hughes and Cooke, with pike fishing being a central theme. Barrie, having suggest a collaboration, illustrated Ted's The Great Irish Pike (1982).

Barrie Cooke's illustration for Hughes's The Great Irish Pike, 1982 (Pembroke College collection)

10 years later Ted demonstrated his own draughtsman's skills with a cartoon of a pike swimming into the jaws of a crow, with this note below referring to its debt to Irish mythology:

The Dagda meets the

Morrigu, on the Unshin,

near Ballinlig

The Morrigu is the crow (Irish goddess of death), the Dagda (a god of wisdom and nourishment) the fish, and Unshin is the river near Cooke's house, Ballinlig, which lies just below an ancient battle field. Accompanying the drawing was this previously unseen poem ('Gur' is the lough in County Limerick where they caught pike for years):

1.Without Gur, God would have given up.

Gur, vesica piscis of the Morrigu, the big pike stark

in her loving cup.

2.The Morrigu came North and standing astride

The Unshin, she let gape the mouth of her cauldron

wide

And bagged the Dagda, like a great kicking pike,

alive inside.

3.At the Battle of Moytura, under the heaped burst wine-skin bodies of the

host,

Through the bottom of Balor's broken eye-socket The Dagda's cauldron

tumbled and was lost,

The cauldron that restored the half-herring dead to pikey drive, they sang, had given up the ghost.

4.They lied.

The cauldron of the Dagda survived, returned, and steams

On the Cooke's table, ringed by chunks of Balor's eye-socket, now benign + calcified,

Reviving freeze-dead pikers to rise and live on in their dreams.

Ted Hughes's cartoon of the Morrigu eating the Dagda, along with notes and poem "Trenchford on Dartmoor", in Barrie Cooke's guest book (Pembroke College acquisition)

Ted Hughes died in 1998, Seamus Heaney in 2013, and a year later Barrie Cooke followed.

Theirs was a private friendship nurtured over many years, the fruits of which might have been lost. Fortunately, their letters, notebooks, and artistic exchanges have survived and are now part of the archive at Pembroke College, Cambridge, under the care of Dr Wormald and his colleagues.

The intention is to catalogue and conserve all the material and make it as widely available as possible, as a resource for all and a lesson in the role friendship can play in the creation of art.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz:

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external