Memphis Group: Will Gompertz reviews show at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes ★★★★☆

- Published

There is a word that links Katy Perry, David Bowie, Back to the Future II, Bob Dylan, Karl Lagerfeld, the architecture of southern India and…Milton Keynes.

It is a word both ancient and modern, a word from the East and from the West; a word that says Elvis Presley to some and Egyptian pharaohs to others.

It is a word that was heard repeatedly on the evening of 11 December 1980 in the Milan apartment of Ettore Sottsass.

The legendary designer and architect had gathered together a select group of fellow creatives, all of whom were at least 30 years younger than their 60-year-old host. They were discussing contemporary design and lamenting how cold and calculating it had become under the austere doctrine of modernism.

The vibrant architecture of southern India, with colourful houses like this one in Tiruvannamalai was a source of inspiration to Ettore Sottsass

The white wine was flowing, the cigarette smoke was billowing, and nobody could be bothered to change the record, which was constantly playing the same song: Bob Dylan's "Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again".

And then, inspiration struck.

"That's it!"

Sottsass said to his hip, young guests, before proposing they unite as a design collective that very night to counter the dogma of formalism. They would create a New International Style, putting emotion before practicality, and what better name to call their enterprise than…

Memphis.

And lo, postmodern design had found its ultimate champions, heralding a new multi-coloured consumer dawn you can see for yourself at the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes, a town that took to post-modernism like Don Johnson to a fuchsia suit in Miami Vice.

The exhibition acts as a chronological tour of 1980s pop culture as defined by the Memphis Group, who launched at the Milan Furniture Fair on 18 September 1981.

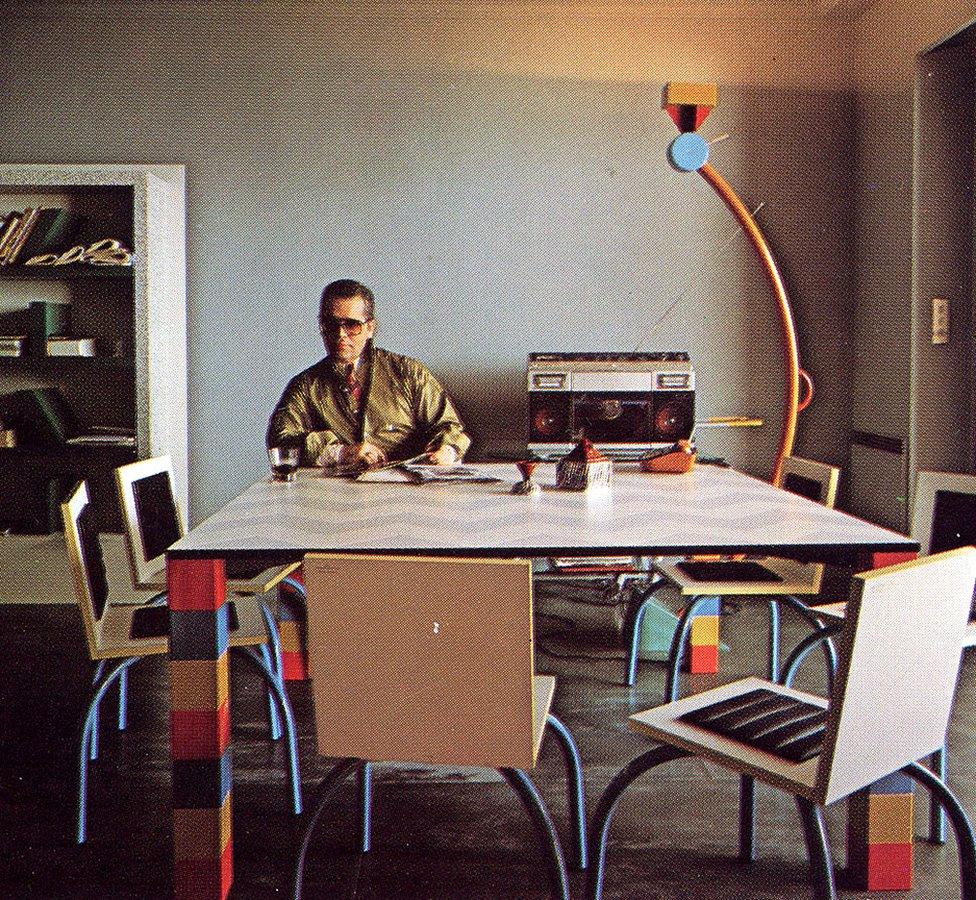

The fashion designer, Karl Lagerfeld sitting in his Monte Carlo apartment with designs by the Memphis Group including "Pierre" table by Sowden and "Treetops" lamp by Sottsass

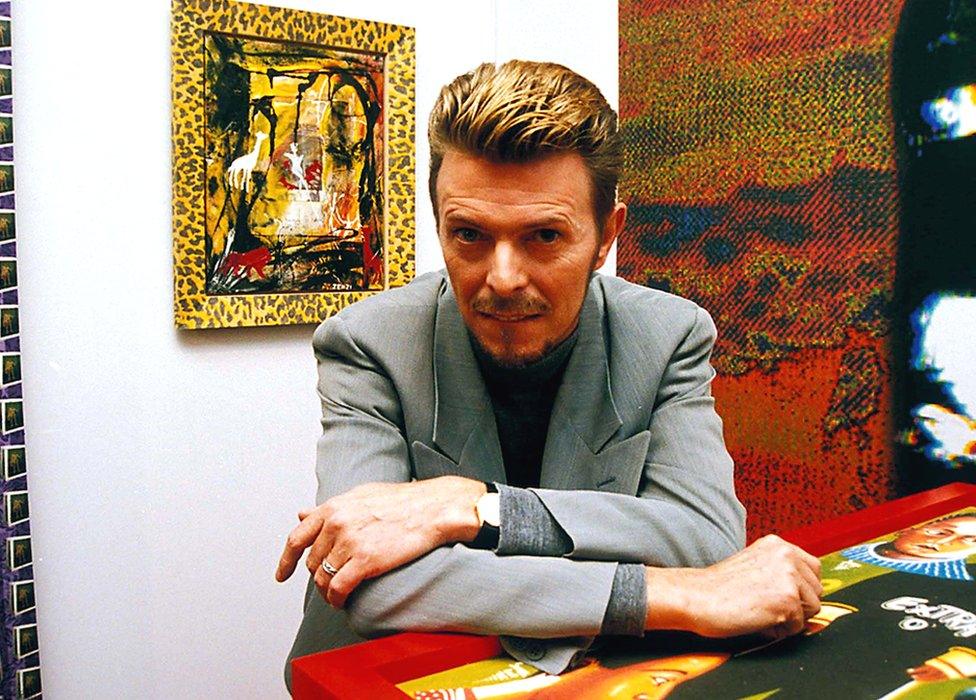

David Bowie, seen here with his own art, was also an avid collector of the Memphis Group's designs, many of which were auctioned after his death

They caused a sensation with their geometric, neo-baroque creations that looked like toytown on acid.

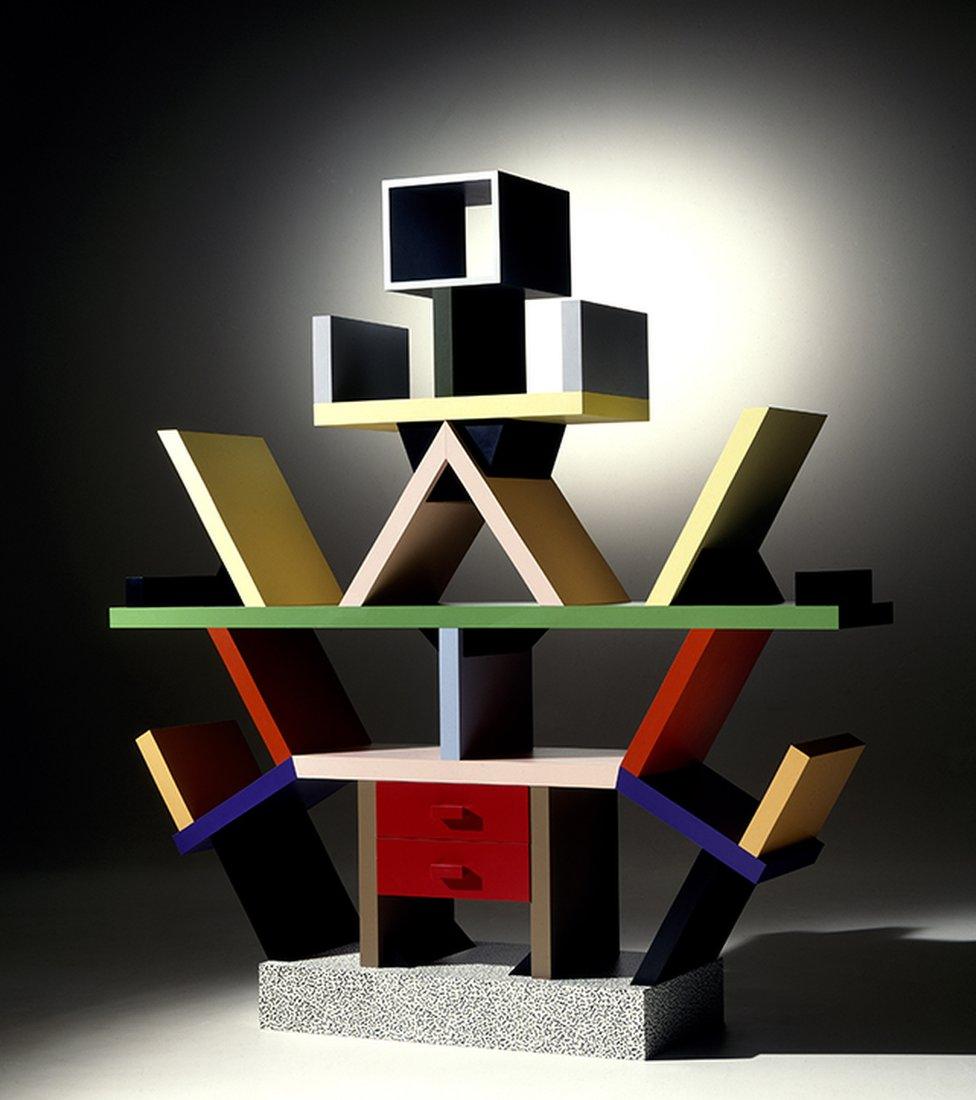

Among the pieces designed by Sottsass were: a tall sideboard covered in a fuzzy pattern like a telly without a signal that sprouted purple shelves coming out at awkward angles (Casablanca); a table lamp that appeared to be made from the contents of a packet of Liquorice Allsorts (Tahiti), and a room divider masquerading as a house of cards (Carlton).

"Tahiti" table lamp in plastic laminate and metal by Sottsass, 1981

Carlton by Sottsass, 1981 (room divider, in wood and plastic laminate)

Ettore - the elder statesman - had set the anti-formalist tone, but it was the Boxing Ring sofa (Tawaraya) by Masanori Umeda that stole the show.

It was at once ridiculous and fabulous: a giant poke in the eye to the humourlessness of modernism's stripped-back aesthetic and its insistence on "good taste" and functionality.

The radical individuals who made up the loose collective trading as Memphis Group were staging a coup with their vulgar, kitsch furniture, lighting and ceramics.

Memphis designers with Masanori Umeda's Tawaraya Bed (1981) with Ettore Sottsass at the back, in the right corner

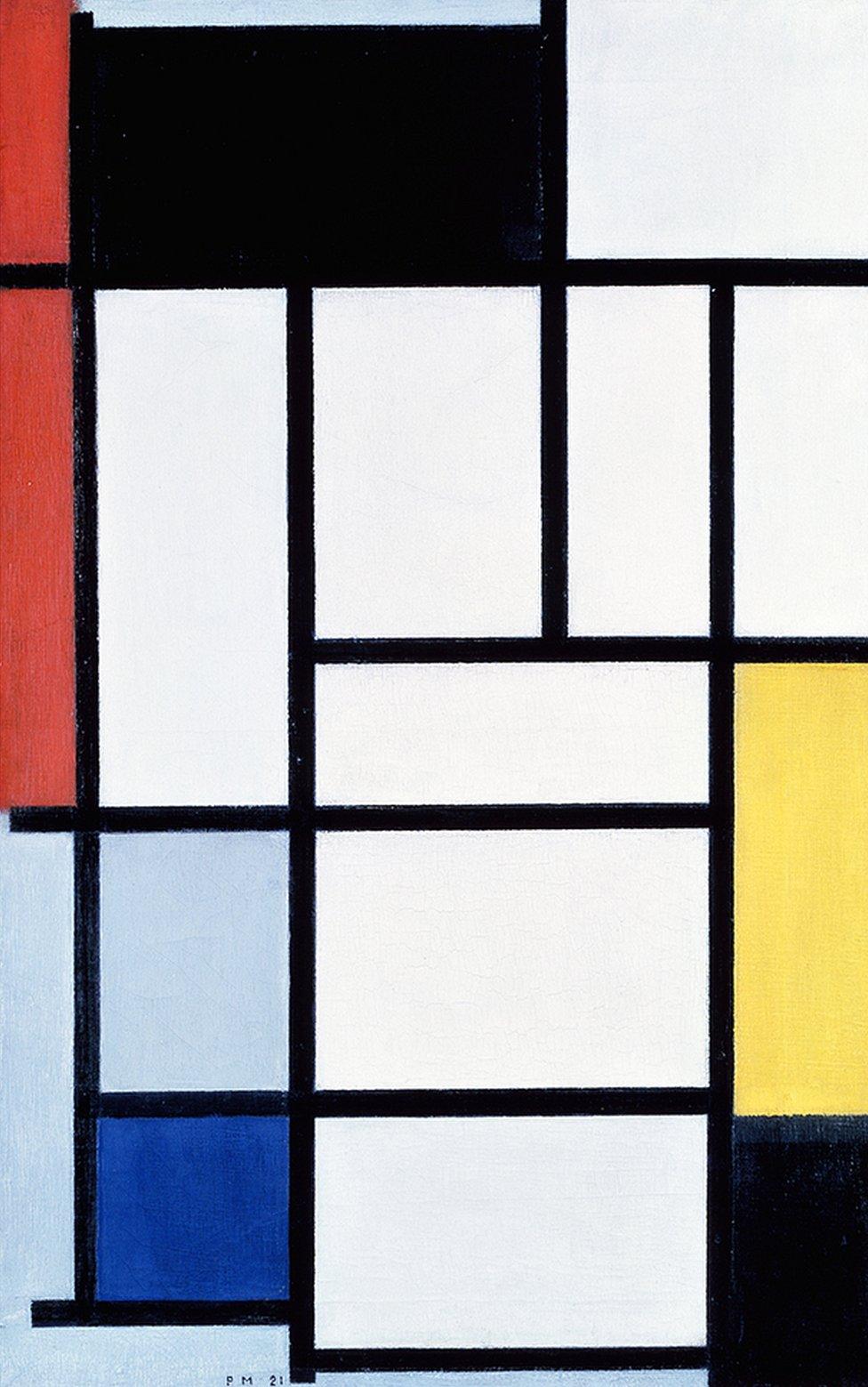

They were the magpies of making, helping themselves to the styles and ideas of classical Greece and the modern art of Jean Dubuffet; the primary colours of Piet Mondrian and the pastel painted houses of south Asia; the geometric abstraction of Russian constructivism, and the pop-sculptures of Claes Oldenburg.

They treated the history of visual culture like a huge pick 'n' mix counter, grabbing anything they fancied to create dissonant combinations covered in brightly coloured laminates that clashed like cymbals.

Bold, brash, and squiggles galore: a synthetic garlic to ward off the minimalist vampires.

The Memphis Group were drawn to the colours of the Dutch artist, Piet Mondrian (Composition with red, yellow, and blue, 1921, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague)

It is their gaudy, joyous world of ebullient expressiveness you enter when walking into the exhibition.

The garish objects sit on black rugs with a deep pile, flanked by fake pot plants with black leaves, accentuating the shiny materials that fill the space. Wall texts give the back story and insights from the original Memphis members, which is helpful in more ways than one: they also give your eyes a break from the ocular assault.

Team Memphis predicted its own demise in the 1981 Milan catalogue, "we are all sure the Memphis furniture will soon go out of style."

I'm not sure it was ever in style.

Even in postmodernism's mid-80s heyday it was only ever as fashionable as mullets and perms.

It was the Wham! of design.

Well, it was in terms of its cool factor and longevity - Wham! broke up in '86, Memphis limped on till '88. Financially they were as far apart as Nigel Farage and Angela Merkel. George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley sold millions of records, Ettore and his merry band didn't sell very much of their stuff at all.

But the beauty of postmodernism is that it is only ever meant to be superficial, it can shape-shift at a moment's notice into something else entirely. Peter Shire's armchair made out of geometric shapes (Bel Air) once seemed frivolous - an eye-catching piece of furniture for a children's TV show - now it looks serious.

The "Bel Air" armchair by Peter Shire (1982) embodied the Memphis style with its asymmetrical shape and contrasting colours

If Memphis meant anything it was that ideas and their communication are more important than comfort and taste.

The show is as much a manifesto for their willingness to challenge the status quo as it is a celebration of a notable design movement.

It came out of Italy's post-war reconstruction and a blighted 1970s.

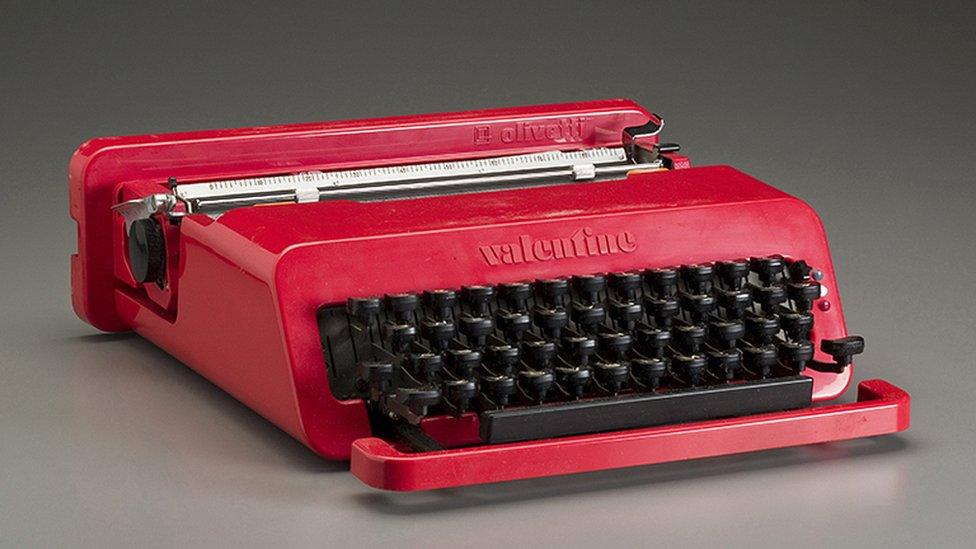

Ettore Sottsass - who died in 2007 aged 90 - was already famous for countering the pervading gloom with his red Olivetti typewriter, which was launched on Valentine's Day 1969.

The iconic "Valentine" Olivetti typewriter by Sottsass, who said he used bright red "so as not to remind anyone of monotonous working hours"

He called it an anti-machine machine, "the sort of thing to keep lonely poets company on Sundays in the country".

Memphis was a rebuke to a cold, glum world.

It was playful and whimsical - iconoclastic even.

Certainly hedonistic.

"Functionalism is not enough. Design should also be sensual and exciting," Sottsass said.

We could do with a bit of that Memphis postmodernist spirit today. In the meantime, you can get a flavour of it at the MK Gallery.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz:

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external