Jennifer Packer: Will Gompertz reviews the artist's show at the Serpentine Gallery ★★★★★

- Published

I was in Hyde Park in London, on my way to Tate Britain to see its new Lynette Yiadom-Boakye exhibition when nature called. My sat nav said 20-minutes to go, my bladder insisted it was more like 20 seconds. I was near the Serpentine Gallery and hoped against expectation it wouldn't be locked down.

As luck would have it, the 1930s teahouse-turned bijoux art gallery was partially open for a press view of an exhibition of new work by the 36-year old African American artist Jennifer Packer - her first major show in a European institution.

It won't be her last.

What can I say?

Other than, relief became revelation as I walked through the Serpentine's white-walled galleries and fell in love at first sight with Packer's remarkable pictures.

It is rare, in my experience, to encounter art of any type - literature, music, film, painting etc. - that blows you away; that has the power and immediacy to take you completely by surprise and stir your soul. Jennifer Packer's expressionistic paintings had that special effect on me.

They vary in size and subject: there are small flower paintings, medium-sized portraits of friends, and one vast, wall-sized interior with a reclining figure painted during lockdown.

All are oil on canvas, and there's not a dud among them.

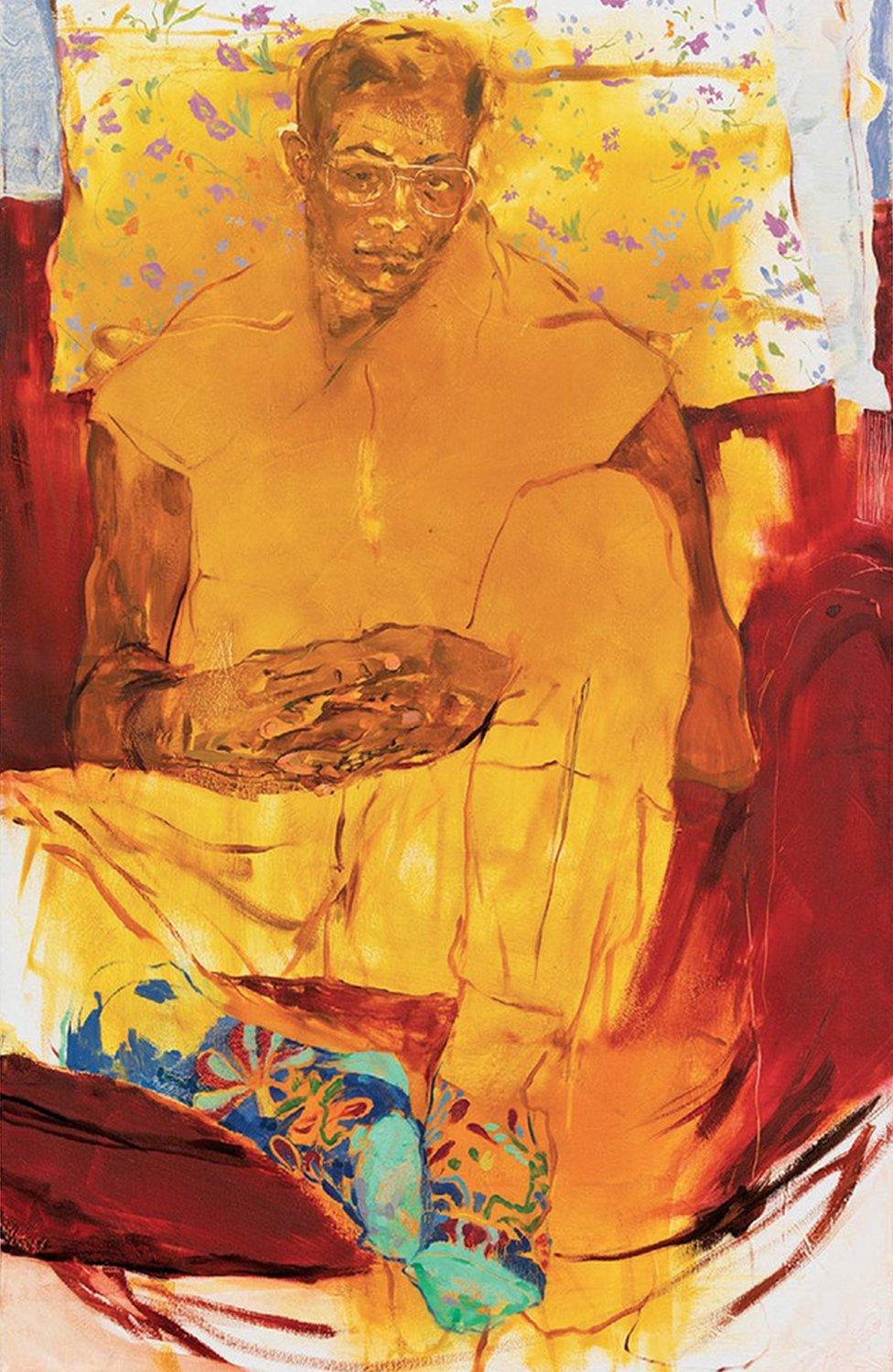

The first painting you see is Tia (2017), a 25in x 39in portrait of a person sitting, feet up, in a red armchair. The figure leans back, head resting on a pillow, with eyebrows slightly raised above a pair of spectacles that have been scratched into the surface of the paint. The subject looks directly at the viewer with a slightly quizzical expression: a warm, calm individual in orangey-yellow clothes framed by fiery red furniture: hot colours, cool character. And a first sighting of a Packer favourite: jolly patterned socks at the front of the picture plane, which, in Tia, reminded me of the ornate flourishes in Henri Matisse's famous Red Room (1908).

Tia by Jennifer Packer, 2017, is on show in her exhibition The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing, which seeks to reflect the desire for knowledge through our senses

Red Room (Harmony in Red) by Henri Matisse is at the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg

His is not the only name that springs to mind when walking through the show.

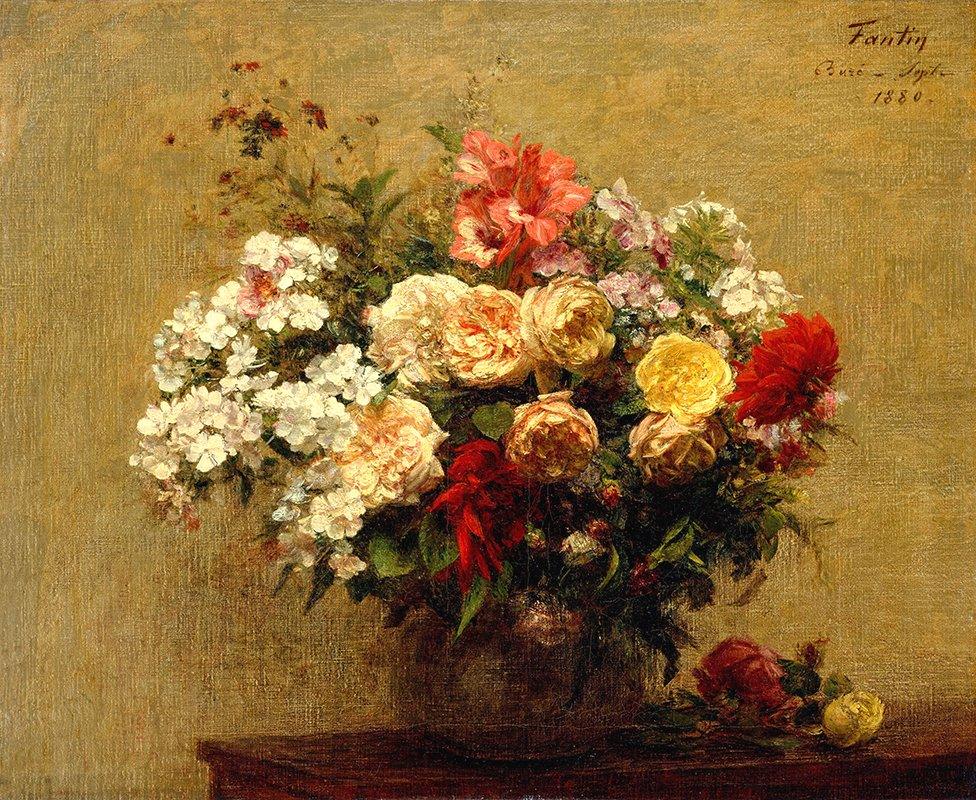

The Bronx-based artist's exquisitely moody pictures of bouquets of flowers captured moments before wilting and withering, obviously hark back to the Dutch "vanitas" paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries, in a journey to the present via the 19th Century French painters Henri Fantin-Latour and Édouard Manet, through to Giorgio Morandi's modernism, and finally the artist's own political sensibility.

Flowers have been a source of inspiration for artists through the centuries including Henri Fantin-Latour's Summer Flowers, 1880

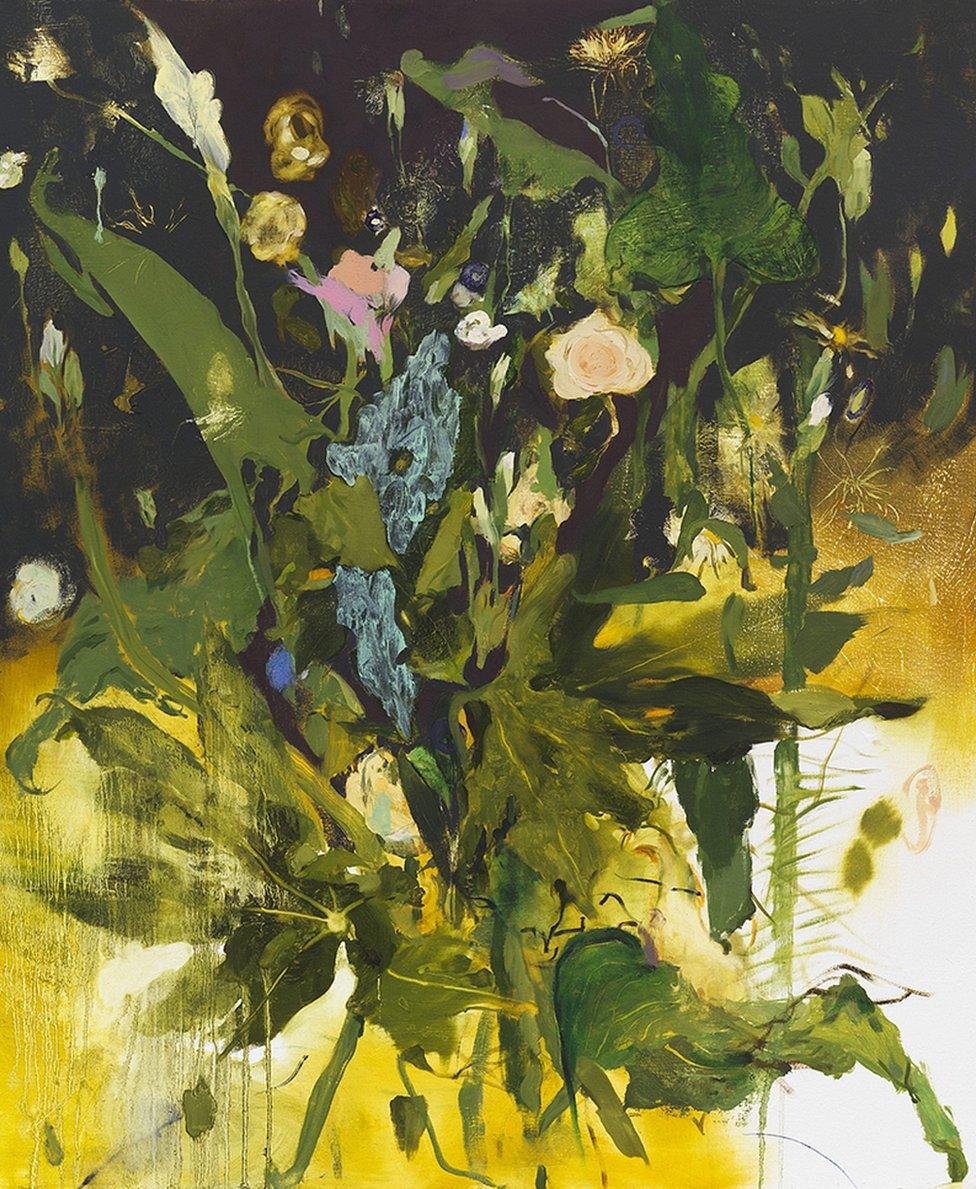

Say Her Name (2017) is a 48 x 40-inch modern masterpiece, a botanic explosion on a background that goes from black to yellow. The unravelling, unkempt flower arrangement consists of smudged green leaves, scumbled stalks, and the occasional pop of blue and pink blossom.

You wouldn't buy such a messy bouquet at the florists, but you'd keep the painting forever.

The lighting is ethereal and unforgettable: the artists of the Dutch Golden Age employed the tricks of chiaroscuro to create drama. Packer achieves a similar atmospheric effect with barely any shadow, relying instead on accelerated tonal transitions and a light source that blushes the surface.

It is a painting of life and death.

Or, more precisely, a painting of a life and a death.

Say Her Name was made in memory of Sandra Bland who died in police custody in 2015, a tragic event that touched Packer deeply.

Packer says her painting Say Her Name "became an expression of an inability to deal with the loss" of Sandra Bland, who died in police custody

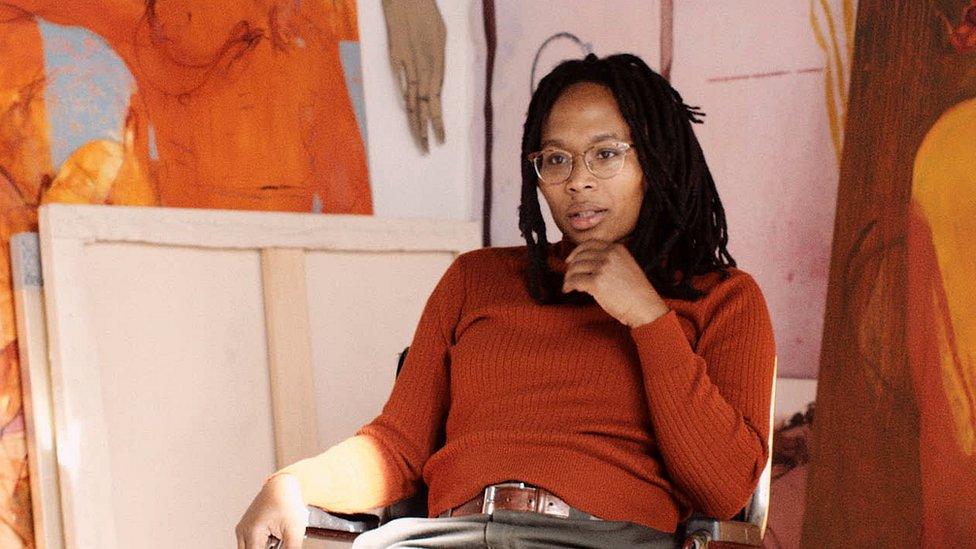

Jennifer Packer says her "inclination to paint, especially from life, is a political one and a way of bearing witness and sharing testimony"

Black lives are an essential component of her work; not just as a subject for her portraiture, but also in defining a space for the African American experience within the auspices of western painting. Her approach is not quite the same way as Kerry James Marshall's, the Chicago-based artist, who overtly inserts the black figure into canonical compositions. Packer is in a similar dialogue with art history, but reveals it in the way she draws on the likes of Caravaggio and Philip Guston to evolve her own unique style.

The energy and sketchiness in paintings such as Jordan (2014) suggest an artist working at top speed - one of those picture-a-day types. But that is not the case, as becomes apparent with closer inspection. The liveliness of the surface is the result of days, weeks, and often months of working and re-working - a process that takes the figurative towards the abstract. Both characters in the painting fade in and out of focus, there one minute, gone the next. The structure of the composition is rock solid, the contents as stable as a rumbling volcano.

Jordan (2014) by Jennifer Packer

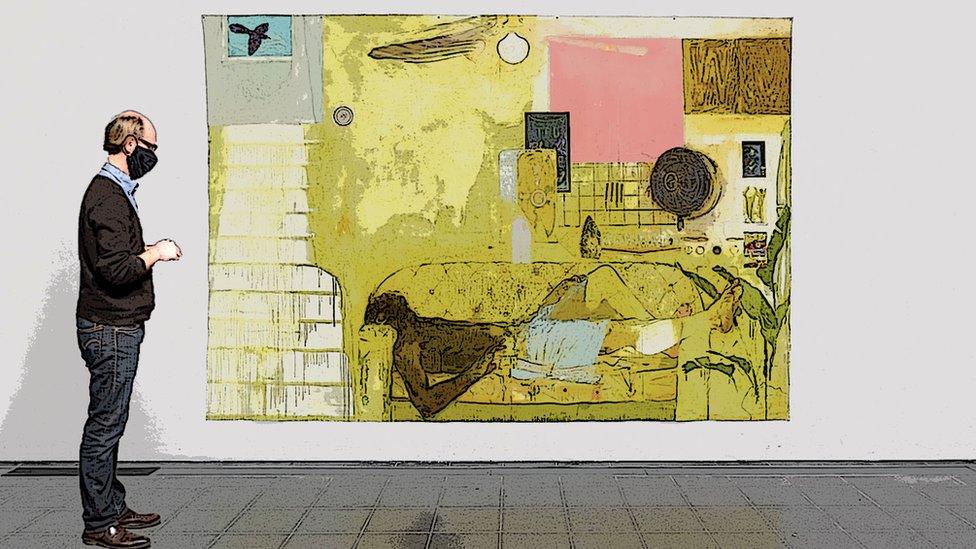

The same applies to the most recent work on the show, the huge Blessed Are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!), Packer's mighty response to the killing of Breonna Taylor by Louisville police officers in March.

It is epic in every sense.

Oil paint has been applied as if a watercolour; the wet substance dripping down white steps leading to a reclining black man in blue shorts, his body cooled by a fan sitting on a sideboard above which is a square block of flat pink paint.

I was only able to spend about five minutes looking at the unframed picture, which would take a day to study properly.

Still, it was long enough to know that it should be in a museum somewhere: it is a work like no other I have seen that marks and reflects on this traumatic year.

Blessed Are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!) by Jennifer Packer

The killing of Breonna Taylor, who was shot in her Louisville home by US police in March, resulted in protests across America

The great art historian Herbert Read said that if a work of art fails to make an emotional connection with you after around 30 seconds, move on. It's sound advice. The flip side of which is, if you find something that strikes a chord, stick around.

I cannot recommend this exhibition highly enough.

There are a lot of good painting shows on in London at the moment - Titian and Gentileschi at the National Gallery, Tracey Emin at The Royal Academy, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at Tate Britain - but if you only have time to visit one, go to the Serpentine Gallery to see this outstanding Jennifer Packer exhibition.

It really is as good as art gets.

I'll see you there.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz:

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external