'Right now, hit songwriters are driving Ubers'

- Published

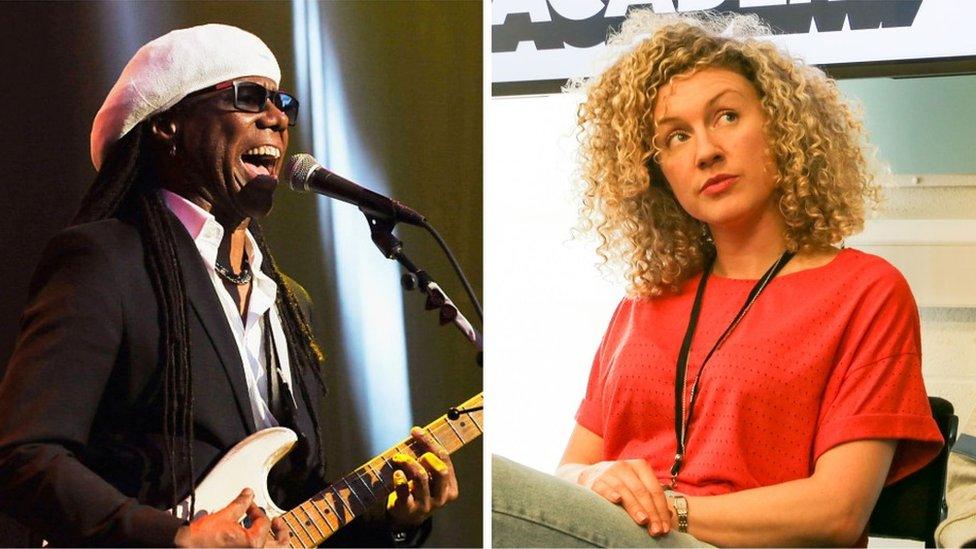

Nile Rodgers and Fiona Bevan were among the stars giving evidence on the impact of streaming

The songwriters behind some of the UK's biggest hit singles "are driving Ubers" to make ends meet, MPs have been told.

Fiona Bevan, who has written songs for One Direction, Steps and Lewis Capaldi, said many writers were struggling because of the way streaming services pay royalties.

Bevan revealed she had earned just £100 for co-writing a track on Kylie Minogue's number one album, Disco.

"The most successful songwriters in the world can't pay their rent," she added.

"Right now, hit songwriters are driving Ubers. It's quite shameful."

'Completely shocked'

Bevan was giving evidence to a digital, culture, media and sport select committee inquiry into the economics of streaming, which now accounts for more than three-quarters of music industry income in the UK.

MPs heard from musicians including Chic's Nile Rodgers and saxophonist Soweto Kinch, as well as music managers Maria Forte and Kwame Kwaten.

Rodgers said he hadn't looked into his streaming income before the Covid-19 pandemic "because my tour revenue has been so substantial that I could support my entire organisation".

After looking into the figures this year, he was "completely shocked".

"We don't even know what a stream is worth," said the musician, adding that "there's no way you can find out," because of non-disclosure agreements between record labels and the streaming services.

"We must have transparency," he told the committee.

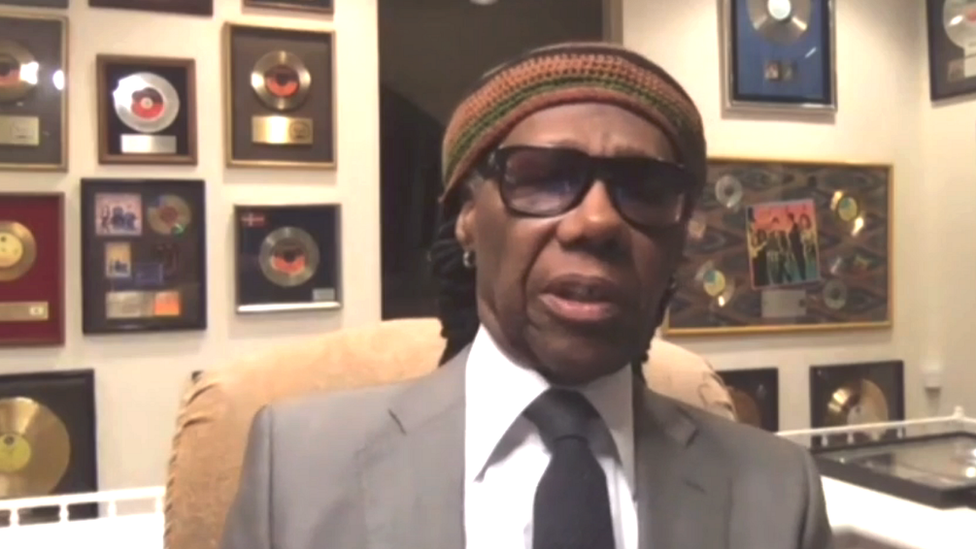

Nile Rodgers spoke to MPs surrounded by gold and platinum discs for his records with Diana Ross, The B-52s and others

The guitarist and producer said record labels retain up to 82% of the royalties they receive from streaming services like Spotify, Apple Music and Amazon Music, calling the system "just ridiculous".

And he accused the major labels of deliberately withholding money from artists.

"I look at the record labels as my partners. And the interesting thing is that every single time I've audited my partners, I find money. Every single time.

"And sometimes, it's staggering, the amount of money."

Rodgers, whose credits include Chic's Le Freak, Madonna's Like A Virgin and David Bowie's Let's Dance, said the industry needed to change the way streaming payments are calculated.

Currently, each play of a song is counted as a sale, which gives labels the lions' share of the income, he said. But Rodgers went on to argue that a stream was more like a radio broadcast, or a licence of the original recording, which would give artists about 50% of the royalties.

"Labels have unilaterally decided that a stream is considered a sale because it maximises their profits," he said. "Artists and songwriters need to update clauses in their contracts to reflect the true nature of how their songs are being consumed - which is via a licence. It is something that people are borrowing from [the streaming services]".

Live music 'eviscerated'

However, Rodgers was optimistic that labels, streaming services, writers and musicians could negotiate a fairer deal; and asked MPs to make the UK a "leader" in regulating the streaming market.

"This can now be a great paradigm shift for songwriters and artists all over the world," he said.

Mercury-nominated jazz musician Soweto Kinch said the timing of the inquiry was particularly important after Covid-19 had "eviscerated" the live music scene.

He said streaming had placed a particular strain on niche musical genres and experimental musicians, because of an overriding focus on chart music.

"We'd never have a Kate Bush or a David Bowie in today's music ecology, because it's very risk averse," he said.

"You are making songs for playlists, you are not taking the incredible musical risks that Bowie might have taken years ago."

Nadine Shah said she had considered giving up music because earning a living was so difficult

The inquiry continues into 2021, and will hear the "perspectives of industry experts, artists and record labels as well as streaming platforms themselves".

At the first session last month, musician Nadine Shah told MPs "many fellow musicians" were afraid to give evidence "because we do not want to lose favour with the streaming platforms and the major labels".

In response, committee chair Julian Knight MP later warned companies against interfering with the inquiry.

"We have been told by many different sources that some of the people interested in speaking to us have become reluctant to do so because they fear action may be taken against them if they speak in public," Knight said.

"I would like to say that we would take a very dim view if we had any evidence of anyone interfering with witnesses to one of our inquiries. No one should suffer any detriment for speaking to a parliamentary committee and anyone deliberately causing harm to one of our witnesses would be in danger of being in contempt of this House.

"This committee will brook no such interference and will not hesitate to name and shame anyone proven to be involved in such activity."

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published24 November 2020

- Published15 October 2020

- Published14 May 2020