The New European bought by consortium from Archant

- Published

The New European was launched on a short run in 2016 to fight Brexit

A consortium including Mark Thompson and Lionel Barber has conducted a management buy-out of The New European, the make-shift weekly print title initially launched on a four-week run in 2016 to fight Brexit.

TNE was owned by Archant, the local publishing group based in Norwich.

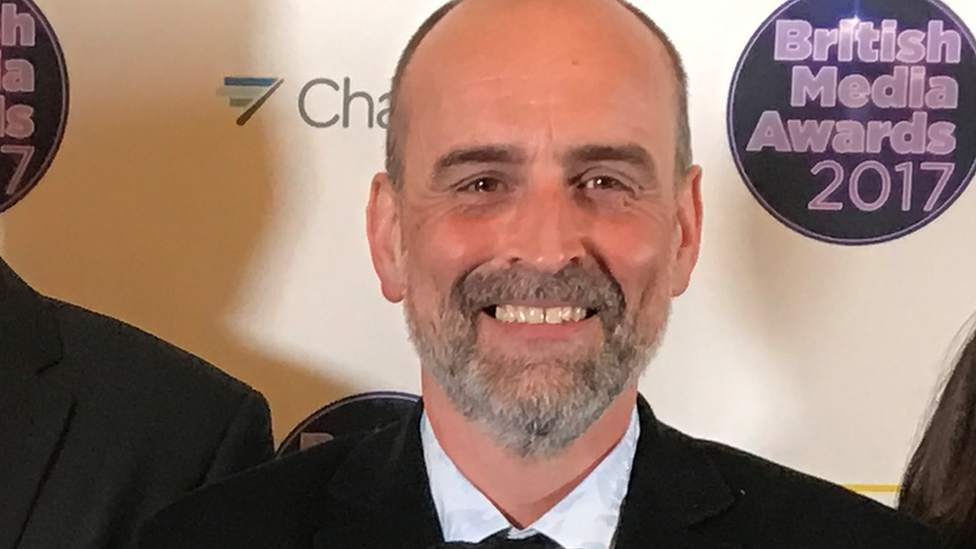

Its chief content officer, former Daily Mirror executive Matt Kelly, led the fund-raising effort, and as of this morning has left Archant to become CEO and editor-in-chief of The New European.

The executive chairman will be Gavin O'Reilly, the Irish businessman who was former CEO of Independent News & Media, and whose father Tony was for many years proprietor of The Independent.

Archant was sold to a private equity group last August.

Investor calls

Kelly was the first editor of TNE, before moving up to be publisher. His backers include influential figures from the world of venture capital and technology: Robin Klein, ex-partner at Index Ventures, co-founder of The Accelerator Group, and now at Local Globe; Taavet Hinrikus, the Estonian founder of TransferWise, an international money transfer platform, who previously helped grow Skype.

The former Daily Mirror executive Matt Kelly, led the fund-raising effort, and is now CEO and editor-in-chief of The New European

O'Reilly and Kelly, who knew each other previously, first discussed the idea while drinking at Piers Morgan's annual Christmas party at The Scarsdale Tavern, a pub in Kensington, west London, in 2019.

The involvement of Barber and Thompson is striking. For Barber, it is his first significant editorial intervention since resigning as editor of The Financial Times (he has started a podcast for LBC, too). He has been a vocal critic of Brexit.

For Thompson, the former BBC director general who is moving toward a portfolio career after a commercially successful reign as chief executive of The New York Times, it is the first well-publicised investment of his own money. Thompson made several million dollars from the sharp rise in the share price of The New York Times under his leadership.

The strong political stance of TNE makes this a noteworthy association. As the boss of the BBC, Thompson was required to abide by strict impartiality rules. The New York Times is a liberal title, though its news reporters are expected to be impartial too. When Kelly first approached him, Thompson was at his home in Maine, north of New York, where he had just finished digging his Subaru out of a snowdrift.

Other backers investing in a personal capacity are: Saul Klein (Local Globe, with his father Robin), Barry Maloney (Balderton), Jeff Henry (ex-CEO of Archant who green-lit TNE), journalist Steve Anglesey, ex-McKinsey partner Cornelius Walter and entrepreneur Niels Kroninger.

Another backer, also investing in a personal capacity, is Ed Williams, the president and CEO of Edelman in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Williams worked with Thompson at the BBC, and spent two hours walking round Kensington Gardens with Kelly discussing the proposal.

There are 14 investors in total, including Kelly and O'Reilly.

Commercial viability

That is an impressive roster of investors. None of them will expect TNE to make them rich. This must be a passion project for them.

Nevertheless, at a time of structural decline in the print market, and Covid-19 leading to further falls in circulation and advertising, profit remains the only guarantee of true independence.

Can The New European be profitable? Yes - but not immediately. And not in a big way - that is, it won't make several million each year - unless people pay for it online.

TNE currently more than washes its face, making £80,000 as a standalone business. But that is based on a shoestring editorial budget of £6,500 per issue, with some costs absorbed by Archant and only three members of staff, including editor Jasper Copping and digital editor Jono Read. That editorial budget will rise by 50 per cent immediately; and Archant will no longer foot the bill for overheads.

As with all print products, lockdown has caused a fall in circulation, but also created an opportunity to grow subscriptions. There are now more than 10,000 subscribers. With 7,000 sales at news-stand, that makes around 17,000 full price weekly sales.

The website gets more than a million page views a month, which is not big. TNE didn't have a website until several months after it launched. The print title, which is £3, will remain core to its future.

There is an intriguing but embryonic plan to crowd-fund the publication later this year, by making a portion of the business available for ownership by members of the public.

The new owners project a loss in 2021, but a return to profit in 2022.

Market opportunity

When launching a new media product, the key question is not whether there is a gap in the market, but whether there is a market in the gap. That is, what evidence do you have that revenues will come in?

Here, Kelly and his team will quickly discover the limits of the UK print market. A hardy perennial in British media - and one that explains the abject failure of the experiment in local TV news - is to look at what happens in America, and presume it can be replicated here, totally overlooking the fact that the US is a much, much bigger country. For curious historic reasons, the UK has a small but very crowded print market.

It follows that the key is to sell in bigger markets. The internet provides that - especially its English-speaking users in America. The remarkable growth in traffic and revenues at The Independent since it went digital only in March 2016 has come largely from America, a trick other publications such as Mail Online and The Economist have also pulled off. (Full disclosure: I was editor of The Independent until that transition.)

Thirty years ago, a liberal print publication might worry about whether titles with similar politics had sewn up the money of all those inclined to pay for such journalism. Today, there is a vast market online, and the evidence is growing that its consumers will pay for content if it's good enough.

Powered by the web, and digital subscriptions in particular, Britain's political magazine culture is in improving health. Titles like The New Statesman, London Review of Books, Times Literary Supplement, Prospect and 1843, a magazine from The Economist, have all grown their paying audience.

The sharpest growth, however, is from The Spectator. It has more sales than at any point since its launch in 1828. It will soon cross 100,000. New editions have been launched in both America and Australia. Such is its digital growth, that coming out of print distribution (which is very costly and, when done through retailers, reduces margins) may be an option for Andrew Neil, the chairman, to consider.

That said, coming out of print probably leads to a loss of influence, especially for a prestige product. There is a value in hard copies thudding on doormats, not least in Westminster; and the heart of many a writer skips a beat on seeing a byline in print.

The Spectator has a very strong brand and voice, and awareness among potential buyers is very high. The same is not true of TNE. In Barber and Thompson, TNE has two former executives with experience of growing digital subscriptions. But the FT and New York Times are established global brands, with general appeal, big budgets, and long heritage. TNE is a start-up. It will need a savvy marketing campaign early on to boost awareness. And to get people paying for it digitally, it will need not only content that is compelling enough, but a website that is fast, beautiful, and navigable.

Mark Thompson stepped down as CEO of The New York Times in 2020 and is one of 14 investors in The New European

The other method of growing revenue, as Thompson demonstrated at The New York Times, is to package and distribute journalism and ideas in different ways. Live events (after the pandemic); podcasts; and spin-off brands (such as those from the successful Guido Fawkes website) could all work. And newsletters are having a moment - whether the sponsored variety, such as those from Politico, or the paid-model of Substack. Perhaps Barber, who is tweeting a lot, could be persuaded to write a weekly newsletter under the TNE brand. They could call it "Barber's Cut".

Editorially, TNE needs to prove it is not just a Remainiac rag. It was formed in the Brexit wars. Its tag-line remains "Brexit News and Political Analysis". But Britain has left the European Union, and there has been a pandemic. Finding an editorial identity for the world after Brexit, which reflects the pivot in our politics from a socio-economic axis (class) to a socio-cultural axis (identity) will be an early, urgent challenge.

Coming up with a new tag-line may assist that process.

It is one thing to pitch yourself, as TNE will, in the centre ground between The New Statesman and The Spectator; but it is quite another to understand, reflect, and shape what that centre ground actually is, in an era of smashed orthodoxies and incessant flux.

TNE has always published a range of material beyond the European issue, including climate change, mental health, and US politics. Shaping its emerging identity is an exciting task for the editorial team. Breaking some big stories will help grow awareness.

There is a certain chutzpah about The New European, which has won several awards in its young life. For most of the past 15 years, the idea of launching a print product has seemed ludicrous. Many attempts have been met with ridicule, from investors and consumers alike. That is why most new media ventures in this space, from UnHerd to Tortoise Media, are digital.

To launch a print title, make a profit, win awards, and then raise investment to power growth, is an unlikely tale. To do it during a pandemic, when already ailing print models have taken a battering, is even more unlikely. TNE's readers are higher earners, mostly over 50, and professionals. And it turns out there's quite a lot of them about who still like the tactile experience of print. As with vinyl and terrestrial television, whose ratings have soared of late, print will be part of the media landscape for many years yet.

So, it turns out, might The New European.

If you're interested in issues such as these, you can follow me on Twitter, external or Instagram, external; and subscribe to The Media Show podcast from Radio 4.