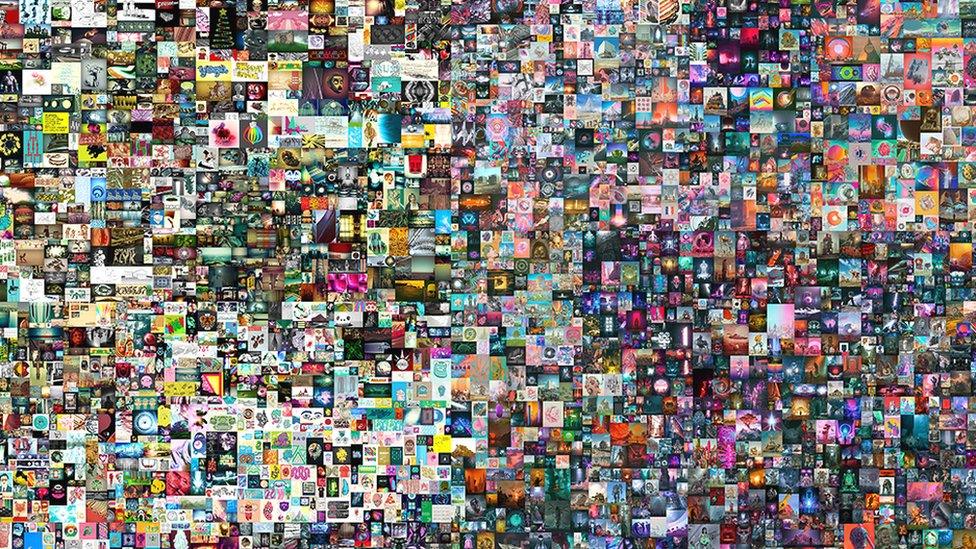

Everydays: The First 5000 Days - Will Gompertz reviews Beeple's digital work ★★★☆☆

- Published

Mike Winkelmann is an American graphic designer. In May 2007 he drew an image of his Uncle Joe, called it Uber Jay (Mike's nickname for his uncle) and shared it online. The next day he made another image and once again posted it online. He did the same thing the next day, and then the next day.

In fact, every day for the past 13 years Mike has uploaded a new image. You can see them on his Instagram feed 'beeple_crap': Beeple being his nom de plume when in graphic artist mode.

Initially, it was a good way for him to market his skills to internet savvy clients, including Apple, Nike, Coca-Cola, Louis Vuitton, and a host of pop stars from Justin Bieber to Katy Perry.

It turned out people liked Beeple.

His Instagram following grew and grew like Jack's beanstalk, reaching the heady heights of 1.9 million today.

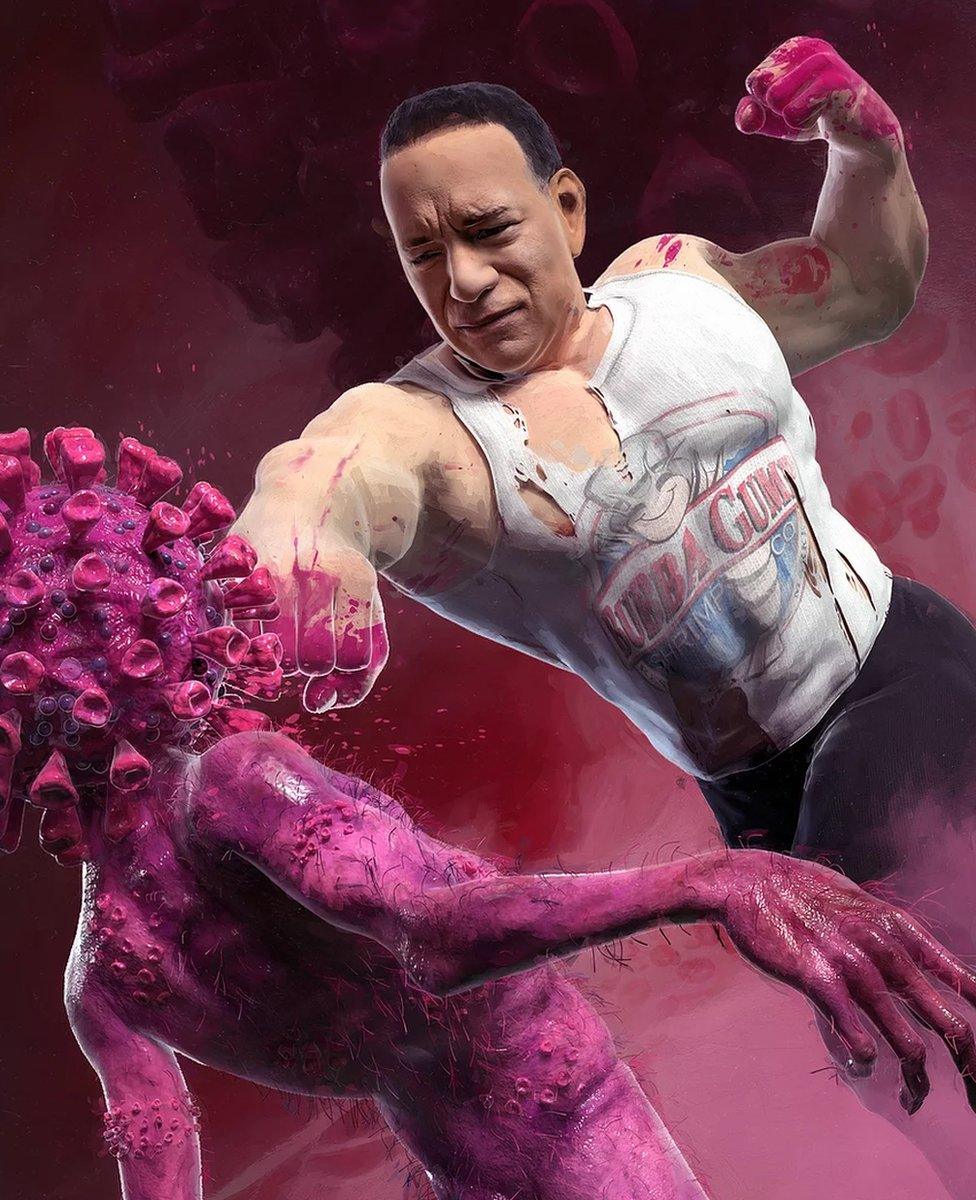

His images became "weirder" and "grosser" (his words) as time went on, and he learnt to use 3D technology.

Nowadays his "everydays" have a sci-fi comic book look. They are often responding to the news agenda or riffing on pop culture, and are typically set in post-apocalyptic futuristic landscapes. Some take him minutes to make, other a few hours.

Home Planet

Boat Parade

His rule is one a day.

I tell you this because Mike has had a big week.

When Covid struck and his design business work slowed down, he started to explore the mind-boggling world of cryptocurrencies, blockchains and Non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which are basically digital certificates of ownership. He discovered that there were some serious players in the virtual game, serious players who would pay serious money for a piece of digital art that came with an NFT that authenticated it as unique.

Mike changed his focus from Winkelmann the designer to Beeple the artist.

And then he had an idea…

He created a collage of all the "everyday"' images he had produced over the years and called it: Everydays: The First 5000 Days.

Tom Hanks beating Coronavirus

He partnered with the auction house Christie's, which had never sold a purely digital work before, an artwork that didn't exist in the real life but belonged in a virtual world. They created an online auction for the work that lasted for two weeks and started the bidding at $100.

The price slowly started to creep up, then it began to accelerate, before going stratospheric in the final minutes, where it was increasing in increments of well over $1 million. The winning bid was $60 million, which, when all the extra charges were added, left the purchaser with a bill of $69 million.

That is a lot of money for an encrypted Jpeg.

Nobody could believe the sum paid.

Not Christies, not art market specialists, and not Beeple (there's a nice video on the Christie's website that shows him watching the final minutes of the auction, external).

Frankly, I don't get it either.

It doesn't make any sense to me.

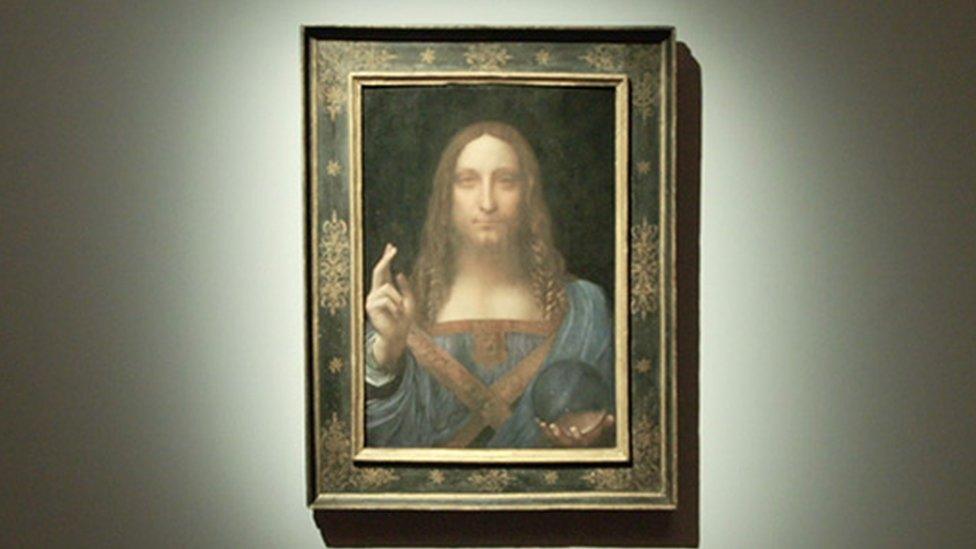

But then nor did someone paying $450 million to buy Salvator Mundi in 2017, an over-restored wreck of a painting that some - but not all - experts attribute to Leonardo da Vinci, or da Vinci and his studio.

The $450 million sale of Salvator Mundi broke the record for any work of art sold at auction

So, best to put money aside and consider Everydays: The First 5000 Days as a work of visual art and not as a tradeable commodity/financial investment.

Is it any good?

Yes, is the short answer.

If you're into the comic book aesthetic, which can be traced back decades, then Beeple is a talented exponent of the genre.

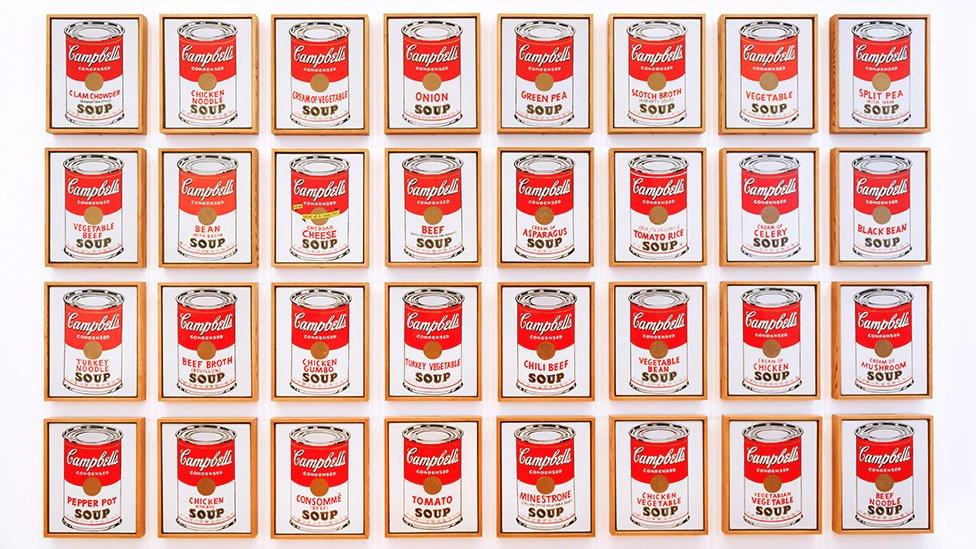

It's not too much of a stretch to make a reference to Hieronymus Bosch's 15th Century densely weird masterpieces, or Andy Warhol's Pop Art, or the macabre nature of Philip Guston's surreal, cartoonish paintings of the late 1960s and 70s.

Confrontation by Philip Guston, who was known for his cartoonish-style of paintings and drawings

Andy Warhol was famously inspired by familiar images from consumer culture

Vibe City by Beeple shows how he draws on consumer culture too

The main difference being Beeple is making his images using a different technique, a different medium, and different materials: he is a 21st Century artist whose time has come in part because of the digital lives we are living because of the pandemic. The speed at which he works is not uncommon in the history of art, nor are the subjects he addresses. It is reasonable to compare him to other artists.

Although, in the context of fine art rather than graphic design, his images lack the psychological intensity you find in the paintings of, say, Jennifer Packer - whose exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London I reviewed recently.

Beeple's artworks read to me more like a comedian's one-liner than a novel captured in a picture, which is what the greatest artists are able to achieve.

Mike Winkelmann aka "Beeple" is now one of the top three most valuable living artists

There is also an issue about the work and the blockchain technology being used to give it value, which should not be overlooked. Digital art might not exist in the real world, but it sure does it some real environmental harm. The energy intensive tech used to create and store cryptoart (a line of code - metadata - that traces back to an image) is exactly what the world doesn't need right now: computers whirring away day and night to generate NFTs consume huge amounts of energy.

Should that be a consideration when viewing the work?

I think so - it is part of the work insomuch as it is the reason for the astronomical price that was paid to own its NFT.

Everydays: The First 5000 Days will go down in history either as the moment before the short-lived cryptoart bubble burst, or as the first chapter in a new story of art.

I won't pretend to have viewed each and every image, but I have seen enough to know it is of artistic and documentary merit.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz:

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published16 December 2022