Why artist Paula Rego remains a master storyteller

- Published

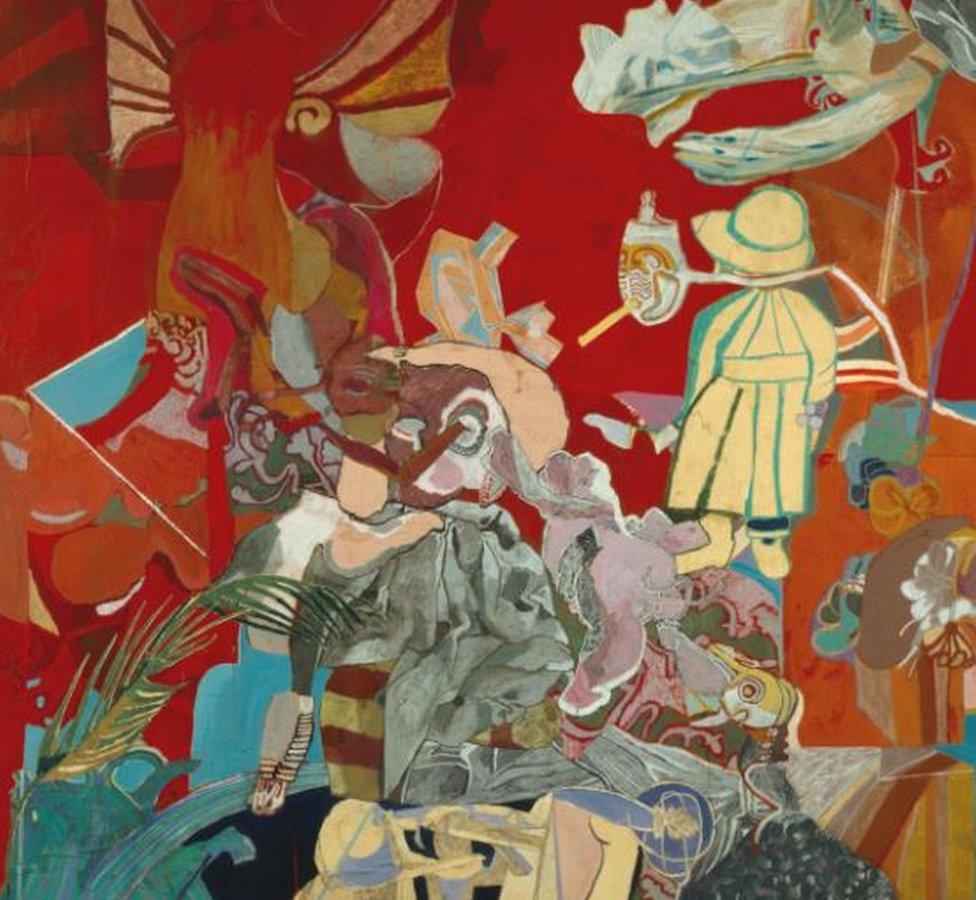

Cast Of Characters From Snow White highlights how Rego uses colourful elements of the fantastic alongside the realistic

The painter Paula Rego is receiving some of the best reviews of her long career for her retrospective show at Tate Britain.

She's lived mainly in London since leaving her native Lisbon as a young woman to escape the conservatism of 1950s Portugal. But her son says she's truly happy only in her studio making art.

At the age of 86 and - as her son Nick Willing explains - now growing a little frail, Rego did not attend the press view for her scintillating new show at Tate Britain. But her intensity and bold imagination leap from the 100 or so images on display.

The retrospective asserts her right to be judged Britain's leading figurative painter, interested above all in the human form (though fascinated by animals too). That judgement on her work is still contested may largely be down to two factors - being Portuguese and being a woman.

Paula Rego has lived in London since leaving her native Portugal in the 1950s

Willing stood in at the Tate event to talk candidly in both Portuguese and English about his mother's work. His 2017 documentary Paula Rego - Secrets and Stories is one of the most insightful films about a living artist.

"For the better part of my mother's life she was struggling to gain any kind of recognition in Britain. She was already in her early 50s when that began to change. For so long it had been much more difficult to be recognised in the art world as a woman. In the 1960s she was probably better known in Portugal."

Rego came to London at 17 to study painting, though for years her life remained split between Britain and Portugal.

Her son is pleased that a 60s piece such as Self-Portrait in Red (1966) is included in the Tate show. Interrogation (1950) shows the talent she had even in her teens: it suggests the state-sanctioned violence which pervaded Portugal's repressive Estado Novo (New State) from the late 1920s.

Many Rego paintings feature an animal such as the cockerel in The Cadet And His Sister

Rego's awareness of the mechanics of political violence and of military repression developed early. Yet it is hard to say what underlies a picture such as the much later The Cadet And His Sister (1988). As in many Rego pictures, an animal appears. Often it's a dog but here it's a cockerel.

Willing thinks most people now barely could imagine how it was to grow up in the Portugal his mother knew when young.

"In the Portugal of the Fascist era the thought police were everywhere - even amongst your friends. You weren't allowed to think certain things let alone speak them. People were often shopped to the PIDE (state security police) for saying the wrong thing and just disappeared.

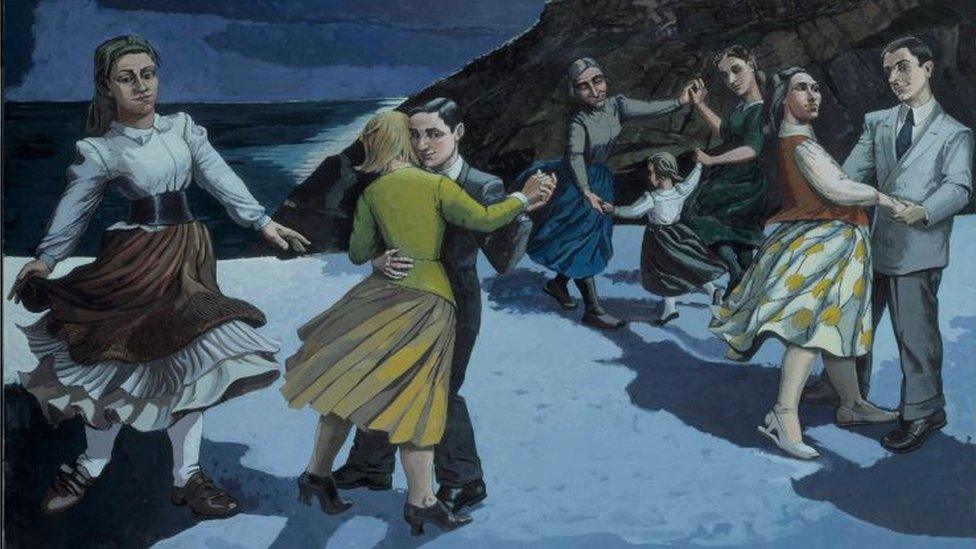

The Dance by Paula Rego

"One of the aspects of coming to London which liberated my mother is that she feels there aren't any ghosts in London.

"When she returns to Portugal she feels the ghosts of her childhood and the memories of the tough times crowding around her. Britain has allowed her to paint the things she needed to paint without the ghosts interfering.

"Of course Portugal is in her soul but she always says she's a Londoner. But really the only place she is happy is in her studio."

The Tate's curator for the show is Elena Crippa. She thinks Rego has reinvented aspects of figurative painting - especially in the depiction of women.

Self Portrait In Red by Paula Rego

"She has created a new way of looking at women and telling their stories. I hope our exhibition really cements her place in art.

"And the show lets us see how she depicted different historical situations, starting with the dictatorship of Salazar in Portugal. Paula always paints from a personal perspective so her experiences in Portugal in the 1960s and 1970s show up in her work."

Rego (who was made a Dame in 2010) has clearly always had a sharp eye for harsh political reality, in Lisbon and elsewhere. But one of the fascinating things about her work is the colourful elements of the fantastic which exist alongside the realistic. It's as though she has picked up imagery from the Brothers Grimm and turned it to her own purposes.

The Little Murderess by Paula Rego is nightmarishly oversized and solemn-faced

In The Little Murderess (1987) a girl is holding a cord presumably ready to strangle a dog (who is unseen). The girl is nightmarishly oversized and solemn-faced. In the background - a dog probably being out of the question - waits a pelican. The picture is shockingly violent or ironic or funny - or perhaps a blend of all three.

Crippa says Rego above all is a storyteller. "She wants to tell the stories of women and from a female perspective," she says.

"Paula truly believes that there is no memory without storytelling. She believes the traditional way of telling a narrative isn't necessarily the way truest to the human experience. She can combine a naturalistic way of drawing and painting with more imaginative elements."

Return Of The Native by Paula Rego was inspired by the the work of novelist Thomas Hardy

But whatever generalisations you make about Rego you need to allow room for the unexpected. Her love of Walt Disney is clear. And there is a large and gorgeous image (1993) inspired by the Thomas Hardy novel The Return Of The Native.

But also there are the paintings from 2004, inspired by Martin McDonagh's play The Pillowman, which had just been a hit in London with David Tennant starring. McDonagh's trademark blend of the ironic, the spooky and the weirdly unexpected may have left Rego feeling she'd landed on home turf.

Willing says his mother has always employed stories and storytelling to explore complex emotions and ideas.

"She's used writers from Hardy to someone more recent like Blake Morrison to inspire her. She believes story helps us live our lives. That's as true now as it was years ago.

The Soldier's Daughter by Paula Rego

"She now finds painting more physically challenging than it was - sometimes the brush will no longer do what she wants it to. But she goes to the studio almost every day still."

So is there a current project?

"Actually what she's doing is the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus, who's an airline pilot. So the ideas are still there even if at 86 it's more of a struggle."

The exhibition runs at Tate Britain in London until 24 October.

Related topics

- Published15 June 2019

- Published15 March 2011