Obituary: Sir Antony Sher, a giant of the stage

- Published

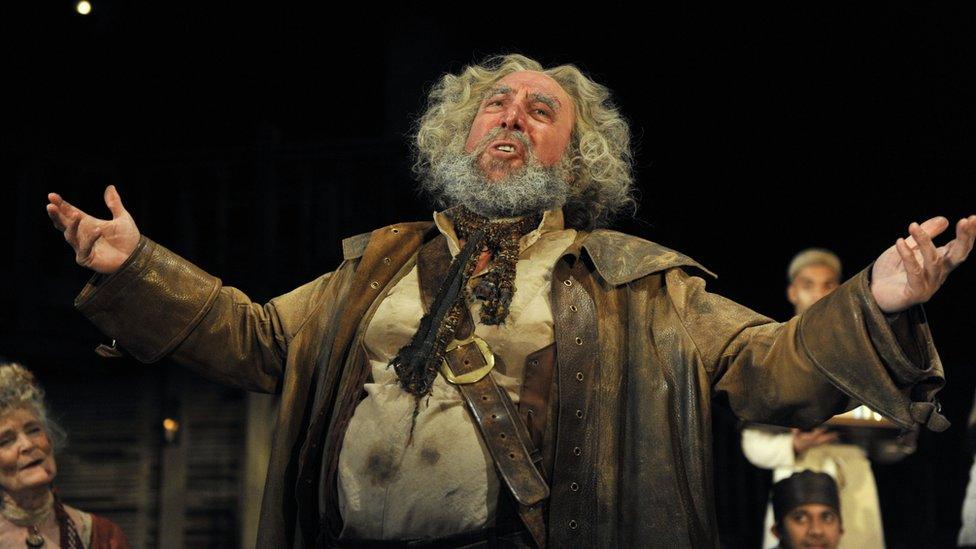

Antony Sher as King Lear. His insecurities helped him portray Shakespeare's most complex characters

Antony Sher, who has died aged 72, once believed that acting was about "becoming someone else".

As a young man, not being himself was appealing. In his own mind, he had much to hide.

He was born a white South African, Jewish and gay. Introduced to the Queen as one of Britain's finest classical actors, he struggled to shake off an inner voice telling him he was an impostor.

But, as he slowly came to realise, the insecurities helped him on stage.

Shakespeare's great characters were outsiders too. Richard III was physically warped; King Lear and Iago were consumed by rage and jealousy; Shylock was part of a spurned community.

With every part he played, Sher confronted a little more of himself, learning to draw on painful memories to master Falstaff, Leontes and Macbeth.

It was a difficult journey, which saw him treated for depression and cocaine addiction. But, by the end, he had changed his mind on a fundamental point.

"Acting is not about hiding," he admitted. "It is about revealing."

Trespasser

Antony Sher began life in Sea Point, a middle-class suburb of Cape Town, on 14 June 1949. He was born with a membrane around his head, which the doctor insisted was a sign of greatness.

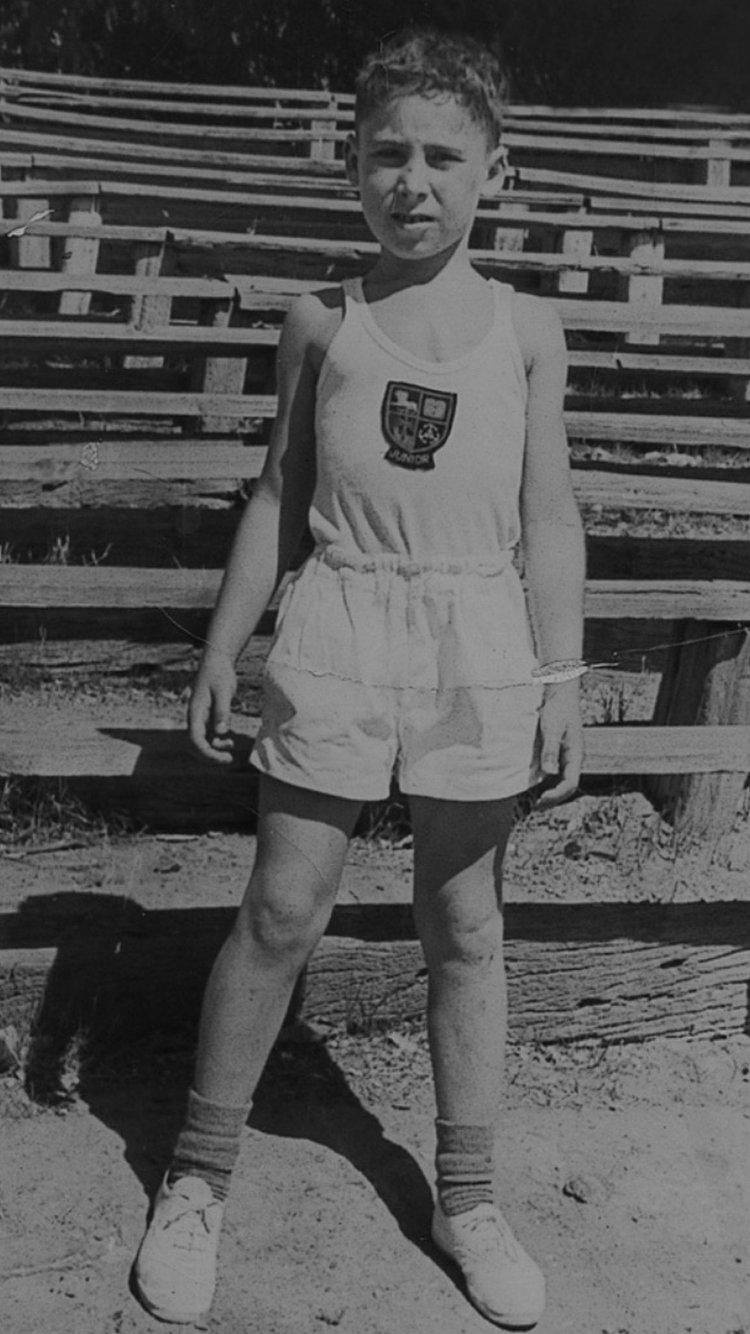

Growing up in South Africa, young Tony felt out of place. He was weedy, artistic and withdrawn - with little in common with his sports-obsessed white classmates. "I always felt like a trespasser," he recalled.

Antony Sher felt out of place in the macho South African culture of the 1960s

Later, there was also a sense of shame. His grandparents were Lithuanian-Jewish immigrants who had fled persecution in Europe, but the family never questioned the system of apartheid under which they now lived.

Sher confessed that he - like everyone he knew - had internalised the message that blacks were inferior. None of them had heard of Nelson Mandela, although Robben Island was visible from Sea Point's beaches.

He did experience anti-Semitism in the South African army. Forced to do national service, he was savaged for his Jewish heritage - and took care to keep his sexuality to himself.

Short, bespectacled and with flat feet, the army despaired at what to do with Rifleman 65833329. Finally, it put him in charge of an empty hut in the Namibian desert - and ignored him.

Rejection

In 1968, Sher left South Africa and travelled to England. His mother - convinced by the doctor that her third son was 'special' - recorded home movies of him arriving for drama school auditions. Success, she believed, was divinely ordained.

The rejection letters cut deep. "Not only have you failed this audition," wrote Rada, "we strongly urge you to seek a different career."

Antony Sher was posted to guard a deserted hut during national service in the South African army

Fortunately, London was crawling with drama schools. Eventually, he enrolled at the Webber-Douglas Academy of Dramatic Art.

Having seen little theatre in Cape Town, Sher could now watch the greats: John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson and Laurence Olivier.

He admired how actors could transform themselves with wigs and prosthetics. It was an attractive skill for a man who was hiding himself.

Sher was shocked to discover South Africa was a pariah state, and ashamed that his family had not taken a stand. He adopted an English accent and said he'd been born in Hampstead.

Antony Sher with his parents, shortly after arriving in England in 1968

He tried to deny his sexuality - first becoming engaged to a fellow student and later briefly marrying a "splendidly named, splendidly spirited woman" called Jo Jelly.

"I went into so many closets," he later admitted.

Not sexy enough

On leaving drama school, the principal made a prediction. Sher, he said, would not succeed as an actor until he was 30. It proved accurate.

At Liverpool's Everyman theatre, he did his acting apprenticeship alongside up-and-coming talents like Jonathan Pryce, Pete Postlethwaite and Julie Walters. But he was rarely the star of the show.

Then, a week after his 30th birthday, a part fell into his lap which made Antony Sher a household name.

The BBC offered him the role of Howard Kirk - a manipulative, womanising sociology lecturer - in a TV adaptation of Malcolm Bradbury's The History Man.

His confidence was initially destroyed on discovering that playwright Christopher Hampton - who adapted Bradbury's novel for the series - had opposed his casting. Sher was not, Hampton argued, sexy enough.

Antony Sher as Howard Kirk in the BBC adaptation of The History Man

But the BBC stuck to its guns. Sher, having gone to a gym in an effort to be 'sexy', delivered a masterly performance as the ruthless, moustachioed bully.

There followed a Bafta nomination, questions in Parliament about the sex scenes and - most importantly - a telephone call from the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Kings and Queens

He had auditioned for the RSC before but had failed to impress. When asked to do a Scottish accent for Macbeth, Sher had attempted an impression of football manager Bill Shankly - and everything had fallen apart.

This time was different. In his first season, he played the Fool opposite Michael Gambon's King Lear - and was then cast as Richard III.

A spectre hung over the role, in the shape of Laurence Olivier. The great man's portrayal of the hunched, murderous King was etched in every actor's memory.

Sher played Richard III on crutches - as a giant, terrifying spider

To play it differently, Sher used crutches. Richard was presented as a frightening, many-limbed beast or - in Shakespeare's words - a "bottled spider".

Riding a wave of stellar reviews, his next project could not have been more different. He became Arnold, a Jewish New York drag queen, in Harvey Fierstein's Torch Song Trilogy.

Sher usually researched his roles exhaustively, but chose to play Arnold straight from the heart.

"My only regret," he later confided, "is that I wasn't out at the time, so I was in the ridiculous situation of not being able to say why this play was so important to me."

At the 1985 Olivier Awards, Sher picked up prizes for both Richard III and Torch Song. "I'm very happy to be the first actor to win an award for playing both a king and a queen," he announced.

Not every part was a triumph. Sher's portrayal of Malvolio in Twelfth Night flopped when he tried - too hard - to inject humour. "It was death by slow crucifixion," he lamented.

Greg Doran and Antony Sher at their civil partnership ceremony in 2005

His performance as Shylock, by contrast, was universally praised. It was also where he met Greg Doran, a fellow member of the cast.

Doran went on to become artistic director of the RSC, Antony Sher's life partner and - when the law permitted - husband.

Under Doran's direction, he was encouraged to look deeper into himself. To play King Leontes, the jealous lover of The Winter's Tale, Sher was encouraged to stop transforming into somebody else and to draw on his own memories.

He looked back and remembered his old rivalry with Simon Callow. There had been a time when Callow seemed to be getting all the parts he coveted.

At times, Sher couldn't bear to be in the same room. "I felt," he recalled, "like Salieri to his Mozart." The two actors eventually set things right after a four-hour lunch at the Caprice.

Antony Sher drew on his old jealousy of Simon Callow to play Leontes in The Winter's Tale

Working with Doran was hard at first. Crockery was thrown after a production of Titus Andronicus - until they agreed a pact never to discuss work at home.

But there were advantages. Sher trusted Doran absolutely, which gave him the confidence to reveal ever more of himself in the parts they created together.

He worked to overcome cocaine addiction through art therapy, and published a range of books - both fiction and autobiography.

Knighted in 2000, Sir Antony suffered stage fright while playing Iago opposite Sello Maake Ka-Ncube's Othello. "It often happens late in a career," he said. "When you're young you can't afford it."

What cured the terror was his one-man show the following year, based on Primo Levi's memoir of his time in Auschwitz.

"There was something about the material that was so sacred, so much bigger than my own ego - that there was no space for my petty feelings," he recalled.

In 2008, Sir Antony took Doran and their production of The Tempest to South Africa, which bore little resemblance to the land he had left 40 years previously.

Together, they explored Cape Town's thriving, desegregated gay nightspots, and spotted a newspaper headline that showed how far both man and country had come. "Jewish boy from Sea Point," it read, "plays Prospero at last".

Sir Antony Sher in one of his final roles - as the vain and boastful Sir John Falstaff

In September 2021, the Royal Shakespeare Company announced that Sher had been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Doran stepped down as artistic director to care for his husband in his final months.

Together, they had just finished a run of memorable productions - including Henry IV part 1, King Lear and Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman.

A fleeting appearance in Shakespeare in Love aside, Sir Antony never had the kind of Hollywood career that others from the RSC enjoyed. The History Man - despite its rave reviews - proved a rare foray into television.

But it never seemed to bother a man who will be remembered as one of the world's great stage performers. As far as Antony Sher was concerned, Shakespeare wrote better scripts.

Related topics

- Published4 December 2021

- Published10 September 2021

- Published5 February 2013