The Hacienda rises again: The Manchester nightclub raves on after 40 years

- Published

Around 1,000 people partied in the underground car park of the Hacienda Apartments on Saturday

Hundreds of middle-aged ravers attempted to recapture the glory days of the Hacienda at a 40th anniversary party on Saturday - in the car park of the flats that now stand on the site. The nightclub's legend is as strong as ever, and its impact is still felt in Manchester.

Every weekend in the early 1990s, Ann Cooper would drive from Yorkshire to Manchester with her husband. They would park their van outside the Hacienda, go inside, then go back to the van to sleep.

"We couldn't afford to stay in a hotel," she recalls. "So I used to come every single week and sleep in a van."

On Saturday, Ms Cooper returned for the club's 40th birthday - although this time not staying in a van.

"The best times of my life were here, without a shadow of a doubt," she says. "It was the music, the atmosphere... it was just the place to be."

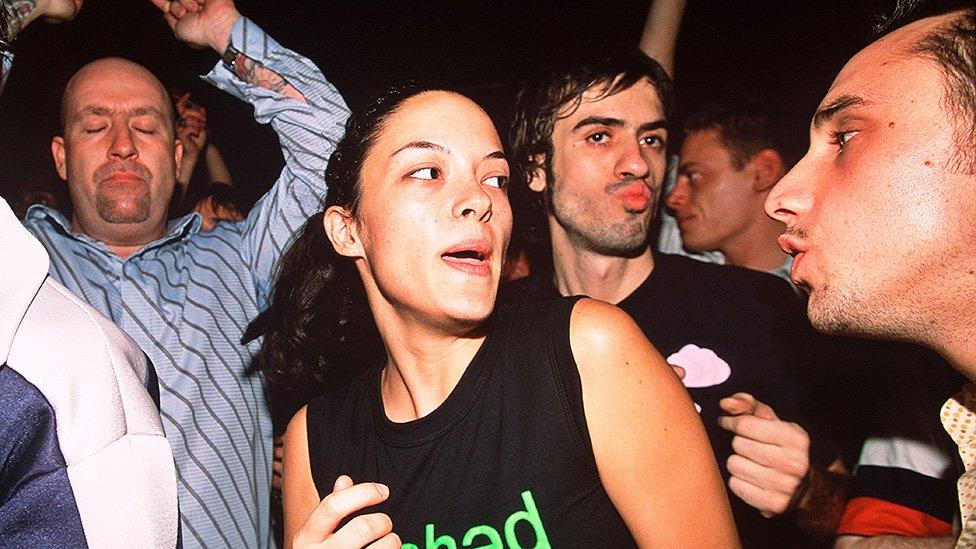

Hacienda ravers in the club's heyday in 1988

The venue opened in 1982, and within five years had became the spiritual home of the acid house movement and the ecstasy-fuelled epicentre of British youth culture.

Jane Ellis used to travel from London every weekend. "It was legendary all over the country. There was no place like it," she says.

"That's why you try to relive it, because you'll never get those times back again. And regardless of how old you are, those memories will never, ever fade."

Around 1,000 clubbers relived the Hacienda's halcyon days on Saturday, with old-school ravers joined by younger clubbers who were not alive when it shut in 1997.

The Hacienda Apartments were built after the club was knocked down

It couldn't be exactly like old times, though. The former yacht warehouse that housed the Hacienda was demolished in 2002, and the Hacienda Apartments built in its place.

So Saturday's event was staged in the block's underground car park, with its concrete pillars painted in the club's trademark yellow and black diagonal stripes.

Who knows what Hacienda and Factory Records co-founder Tony Wilson would have made of it. Wilson, who died in 2007, opened the venue with the band New Order as a "cathedral" for Manchester's youth.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

After it shut, he declared that "nostalgia is a disease" and argued that erecting flats in the city centre was more important than preserving the original building.

If nostalgia is a disease, it's one people don't mind catching.

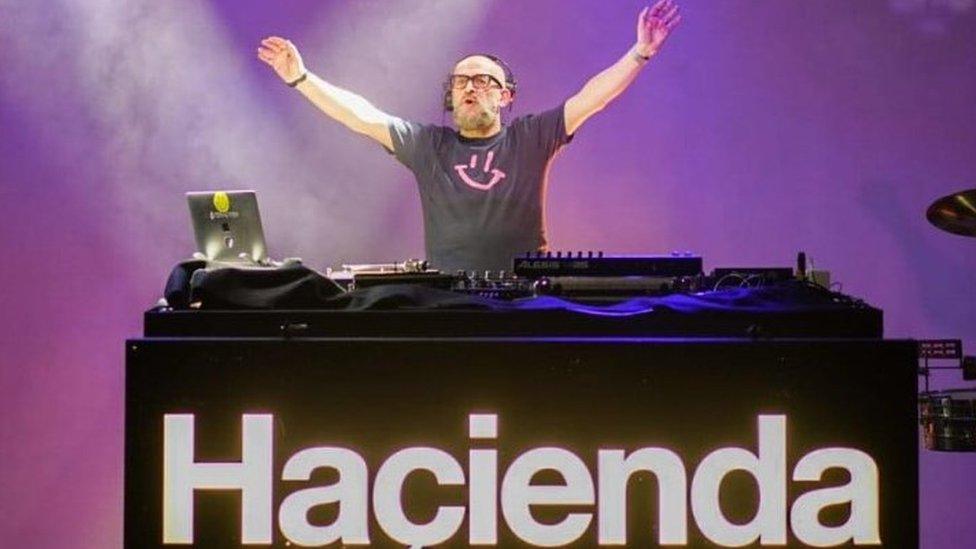

When a 24-hour Hacienda-branded virtual party was held on New Year's Eve, it attracted four million viewers, organisers said. Saturday's rave was also streamed online and raised funds for The Christie cancer centre and the Legacy of War Foundation's work in Ukraine.

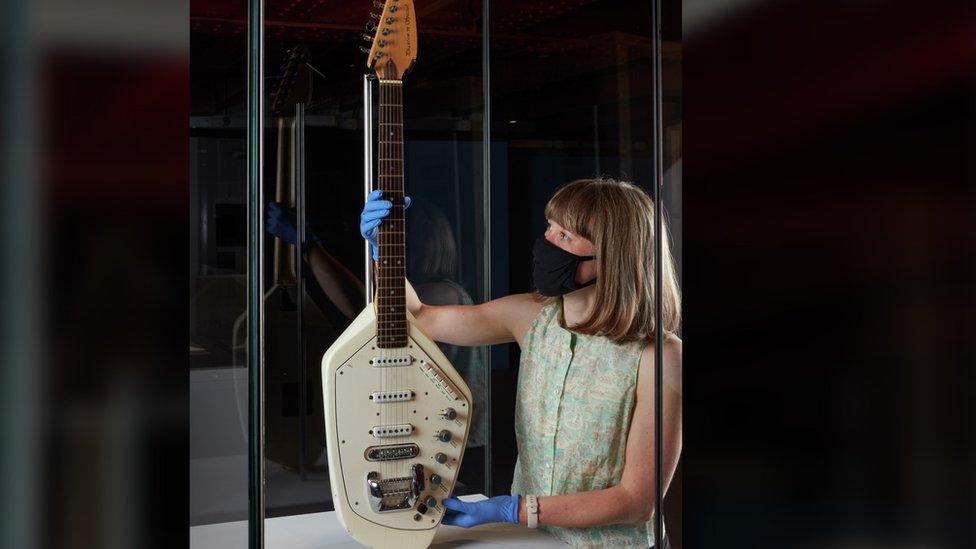

Hacienda exhibits are on show as part of the British Pop Archive at the John Rylands Library in Manchester

A BBC documentary is being made about the Hacienda, artefacts from the club feature in the new British Pop Archive exhibition, and a book about the venue's fashions is coming out.

Meanwhile, Hacienda Classical events have been held everywhere from the Royal Albert Hall to the Glastonbury Festival.

And on Friday, Manchester's hottest current rapper, 22-year-old Aitch, released a new single harking back to the Madchester heyday, on which he raps that he wants to "rave like it's '89".

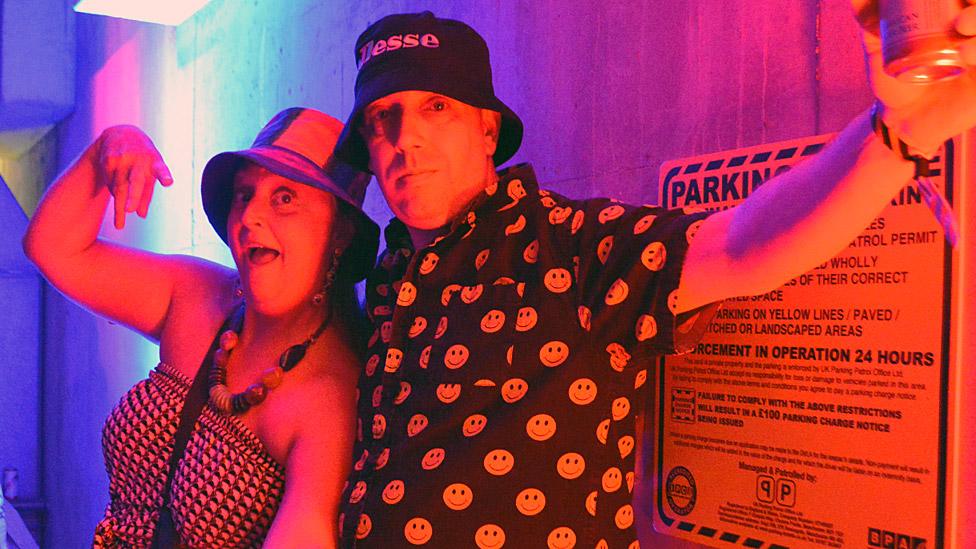

Julie Bancroft (left) worked at the Hacienda on its opening night

The original club was not an immediate success. Julie Bancroft worked on its reception on the opening night.

"I had to stand and hand out roses to all the women who came in," she says. "To be honest, it was dead quiet."

What does she remember about that night? "Bernard Manning." The politically incorrect comedian was on the bill on the first night, alongside New York funk rock band ESG.

Things did improve. "I used to do all the memberships downstairs. They were queuing for miles to get a membership," Ms Bancroft recalls, speaking in the car park on Saturday.

"I just had the best time in my life. It means a lot. I spent a lot of my life here with all these people."

DJs including Greg Wilson appeared on Saturday, with the show streamed online for charity

The club went through three phases, according to journalist and author Andy Spinoza, who was Hacienda member number 9262.

"There was the indie-rock phase, where it was very poorly attended generally. It lost a lot of money and it seemed to be too big for the audience," he says.

"It was only when rave music took over that, suddenly, the club appeared to be built for an audience that didn't even exist 10 years earlier. It was cathedral-like. It was a transcendental experience - obviously enhanced by mood-altering drugs."

He recalls a line that was often quoted at the time to describe the euphoric atmosphere - that it was like "when a goal is scored at a football match - for six hours".

Saturday's event was split into two sessions, with up to 500 people at each

Five Hacienda anthems

Rhythim Is Rhythim - Strings of Life

A Guy Called Gerald - Voodoo Ray

808 State - Pacific State

Sterling Void - Runaway Girl

Inner City - Good Life

"And then it went into a gang-chester, Madchester, slow, horrible decline phase," Spinoza continues. "I've had the best nights of my life at the Hacienda. I've also had some really rubbish, miserable nights."

The legend may have "grown out of proportion" since its closure, but the Hacienda doesn't just live on in nostalgic memories. It also changed the face of the city, he believes.

In his forthcoming book Manchester Unspun, Spinoza argues that the club kick-started the regeneration of the city centre and paved the way for the skyscrapers that now tower over the site, and the new £186m arts venue The Factory - named after Wilson's label.

"To me, there's a daisy chain of cause and effect, which started with the Hacienda nightclub, which gave the confidence for other independent operators to come into Manchester city centre - which really was a ruin and, apart from a couple of theatres, was dead at night," he says.

"The city would have developed [without it], of course. But would it have developed with the same confidence, the same international influences? Would it have developed those parts of Manchester city centre that have sprung up in the same way?

"I don't think it would, because the Hacienda was Manchester simply celebrating itself - not needing London's permission, but not parochial."

Father and son Gerard P Campbell (left) and Gerard J Campbell at the 40th anniversary party

The club's interior was designed by Ben Kelly, who repurposed industrial and functional elements to create a hedonistic playground.

Factory Records graphic designer Peter Saville agrees that the Hacienda was "a pivot point" that made it possible to envisage a future for Manchester after the industrial era.

"Without a doubt, the Hacienda was the moment where Ben Kelly and Factory showed what the old city could be," says Saville, who went on to lead Manchester's cultural strategy for the council.

"In a way, Ben's industrial aesthetic was like a phoenix rising out of the ashes of the old industrial city as the reinvented post-industrial city."

'Not being sold'

Apart from the drug dealing, it wasn't a place for consumerism. Whether by accident or design, neither Factory Records nor the Hacienda were well-run, profitable enterprises.

"People recognised that this was not a business," Saville says. "They recognised that they were not being sold something. They were not punters.

"In a way, it was like a giant youth club. It belonged to the people who went there, and I think that's very much at the root of the affection.

"It was theirs. It was made for the young people of Manchester."

Related topics

- Published19 June 2021

- Published4 January 2021

- Published28 June 2017

- Published7 September 2016

- Published12 August 2015

- Published22 May 2012