BBC presenters: What's behind the large number leaving?

- Published

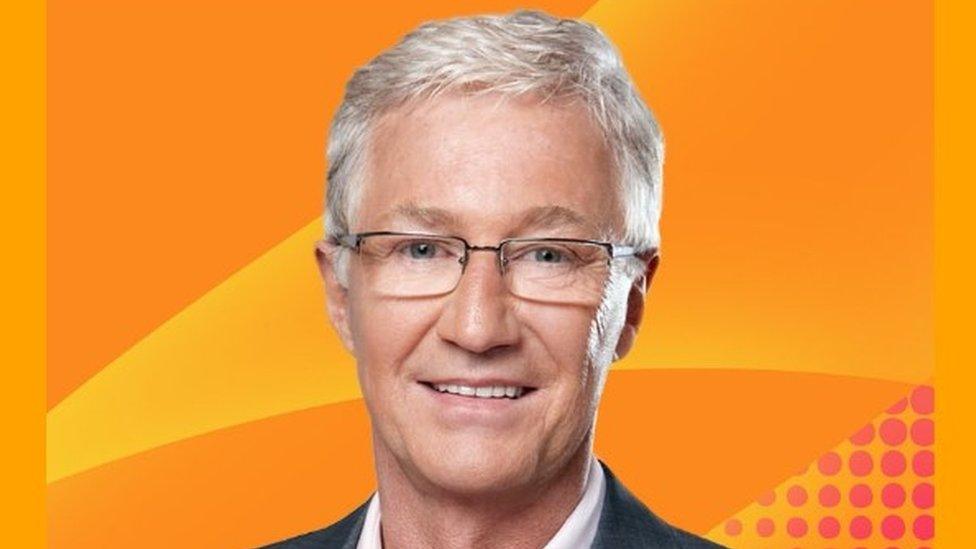

Paul O'Grady left Radio 2 after management forced him to share his slot with Rob Beckett

A large number of presenters have left the BBC in recent months - either by force or by choice. Their departures have invited some uncomfortable headlines and questions for the corporation in the process.

And yet, it is hard to pinpoint a single driving force behind the recent exodus, because there's a whole host of reasons for it.

Radio 2 is going through a particularly tumultuous time, while many of the biggest names in news and podcasting have been lured away.

Vanessa Feltz, Simon Mayo, Andrew Marr, Peter Crouch, Emily Maitlis, Jon Sopel, Dan Walker, Steve Wright, Paul O'Grady, Craig Charles, Graham Norton, Shaun Keaveny and Sue Barker are some of the biggest names who have either been poached, dropped or demoted. Many of them have left the corporation entirely, although a few still do some work for the BBC.

There are credible industry rumours that another popular BBC podcast is also about to jump to the commercial sector at the end of its current season, taking its presenters with it.

But what is behind the current raft of departures?

Sopel and Maitlis will not be as restricted by impartiality rules at Global as they were at the BBC

"Each one will be unique to the individual, but broadly speaking, there's a handful of reasons people are making the choice to leave," says Jake Kanter, media correspondent for the Times.

"A big one that we've seen in recent months and years is reorganisation at the BBC, particularly in the newsroom. A lot of that is driven by the need to reduce costs, and therefore a lot of people have simply taken voluntary redundancy (VR) and left by choice."

The BBC's VR programme, a result of cost-cutting measures, external and a drive to move more staff out of London, has seen many experienced producers and journalists leave - a brain drain that often goes underreported compared with the departures of celebrities.

"But there are lots of other tensions at play," Kanter continues. "For example, top stars absolutely loathe having their salaries published."

Since 2017, the BBC has been required to publish the salaries it pays sections of its top talent. Simon Mayo described it as an "annual turkey shoot", while Graham Norton said it was "not comfortable and not nice". Both have left their BBC radio jobs in recent years.

Steven Barnett, professor of communications at the University of Westminster, says: "Because the BBC was forced - partly through a campaign driven by a self-interested press - to reveal top salaries, its commercial competitors know exactly where to pitch their offer.

Graham Norton still hosts his BBC One chat show, but left his Radio 2 show to join Virgin Radio

"If a presenter is offered a 50% increase in salary without the hassle of a public spotlight on their earnings, that's a very attractive proposition even for those committed to the BBC's public service ethos. It was a terrible mistake to force the BBC to reveal its top talent salaries, and I suspect this problem will only get worse."

Some stars, like Zoe Ball and Gary Lineker, have taken pay cuts following the scrutiny. But many talent agents won't be best pleased when their clients do this, as they lose some of their commission in the process.

Kanter suggests: "What we're going to see increasingly, I think, is the BBC effectively hiding salaries through its commercial division or independent production companies.

"And it's not just salaries - top news stars have their third party earnings disclosed if they're doing a conference or after-dinner speaking gig, and that is very unappetising for a lot of presenters."

The salary publication acts as what former director general Tony Hall described as a poacher's charter, external - giving commercial rivals a chance to outbid the BBC for top stars.

This issue is compounded by the ever-expanding media industry, which means there are more companies around to do the poaching. Feltz, for example, moved to the recently-launched Talk TV, while the huge investment in podcasts has seen Maitlis, Sopel and Radio 1's Chris Stark move to Global.

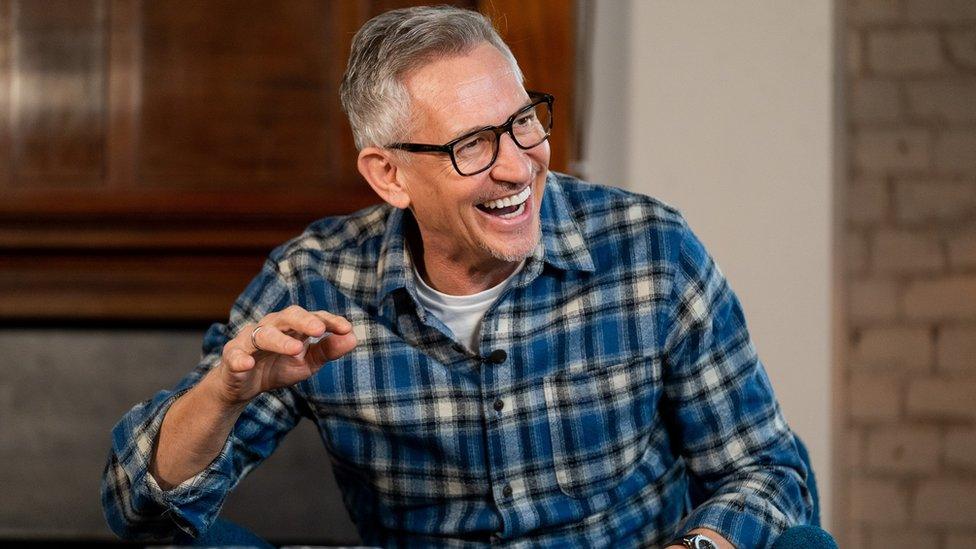

Match of the Day host Gary Lineker has stayed at the BBC - but taken a pay cut

"It's important to remember that because of progressive government cuts since 2010, the BBC has suffered a 30% cut in revenue," says Prof Barnett. "A growing number of broadcast competitors have deeper pockets and can afford to lure on-screen talent away."

But some feel it isn't necessarily a bad thing when long-established presenters move on.

Talent manager Chris North, who identifies, nurtures and promotes up-and-coming presenters, says: "Evolution is inevitable in every walk of life. When people move on, for whatever the reason, it creates an opportunity for new talent."

He points out: "Career development for everyone is cyclical - the people who are now moving on once replaced someone who made way for them. That's how the conveyer belt of talent works. I don't understand why people would be confused about not wanting new presenters to come through - it is inevitable."

Others think the BBC should let its biggest names leave rather than offer huge sums to keep them, and grow a new generation of stars instead.

For example, Alex Jones was relatively unknown to national audiences before she was hired by The One Show, but that move made her a star. Why shouldn't the BBC do that more often, and let long-established names leave?

After Christine Bleakley left The One Show, the BBC hired the relatively unknown Alex Jones (pictured)

It's also worth remembering that moving to a rival broadcaster is not always successful.

Adrian Chiles and Christine Bleakley famously failed to transplant their chemistry from The One Show to ITV's Daybreak. And while GB News has attracted and retained some top talent, such as Eamonn Holmes, former BBC presenters Andrew Neil and Simon McCoy did not stay for long.

For stars who made their name in news, such as Sopel, Maitlis and Marr, the freedom offered by rivals is a significant attraction.

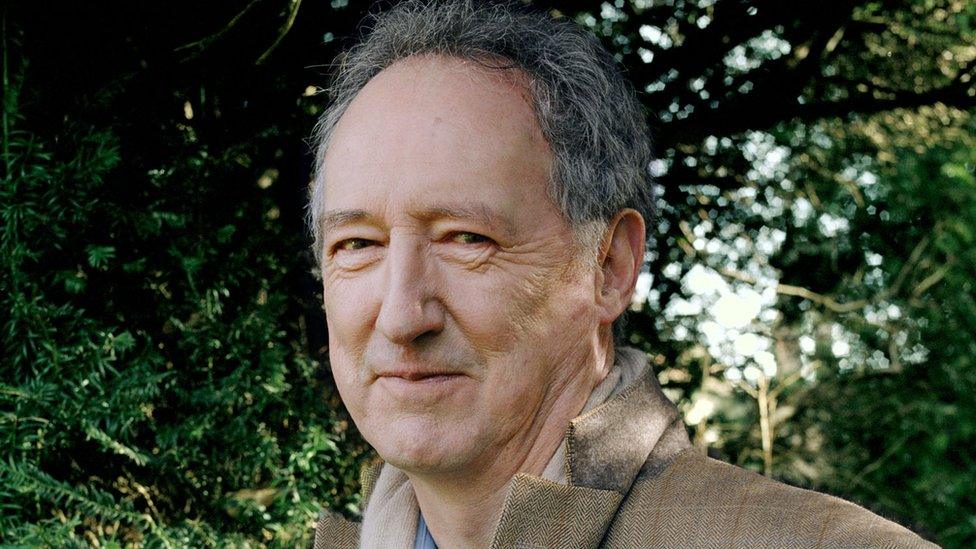

When he left, Marr said he was looking forward to "getting his voice back" - a reference to impartiality rules at the BBC. Maitlis, meanwhile, was told off for impartiality breaches during her time at the corporation.

Getting impartiality right can be tricky - people on both sides of the political divide regularly complain the corporation is biased in favour of the other. Maitlis has also accused the BBC of "both side-ism" - in other words, providing a superficial balance.

Dorothy Byrne, former Head of News & Current Affairs at Channel 4 News, says: "Key journalistic talent now leave because they believe rightly that the BBC's erroneous interpretation of regulation regarding impartiality prevents it from telling viewers and voters the truth. The BBC has always been a timorous beastie. Now it's a great big fat frightened rat."

The BBC's director-general Tim Davie has said: "Trust in our impartiality is not a nice to have, it is the very essence of who we are. It is the bedrock of why people come to us."

Steve Wright has hosted his weekday afternoon show on Radio 2 since 1999

Perhaps the departures that attract the most uproar are when a presenter doesn't want to leave - but the BBC is looking to appoint someone new who will attract younger listeners and viewers.

Announcing his exit from weekday afternoons earlier this year, Steve Wright said: "My friend and boss Helen Thomas, head of Radio 2, said she wanted to do something different in the afternoons." He is being replaced by Radio 1's Scott Mills, but will continue to host Sunday Love Songs.

O'Grady left the station after being forced to share his slot with Rob Beckett, a younger comedian who co-hosts a successful parenting podcast.

Elsewhere, Craig Charles lost his weekend Radio 2 show (although he is staying on 6 Music). "I can see their point. I'm on 6 Music six days a week [but] the Radio 2 show was performing well," he said earlier this week. "They couldn't give me any reason other than, they just wanted a change."

Craig Charles said of his Radio 2 departure: "They couldn't give me any reason other than, they just wanted a change"

The number of these changes, and the speed of them, can drive audiences up the wall.

Addressing Radio 2 listeners in the Radio Times, former BBC producer Trevor Dann said:, external "If you're seething about the high-handed way the bosses are treating you, don't bother writing to complain, because they don't care what you think."

A spokesman for the station said: "Throughout the years Radio 2 has stayed relevant to its millions of listeners by evolving its schedule. We're grateful to all the presenters, past and present, who have played their part in the success of the station, and we also look forward to welcoming refreshed shows, new ideas and different voices to Radio 2, as we always have done."

"Whilst we of course want new listeners to discover Radio 2, we are focused on providing the 14.5 million people who tune in each week with a brilliant range of programmes, hosted by some of the UK's best-loved presenters. Radio 2's multi-generational appeal serves a 35+ audience, a target which hasn't changed in decades, and we are proud to feature the best music from the 60s to the present day, which is key to the station's continued success."

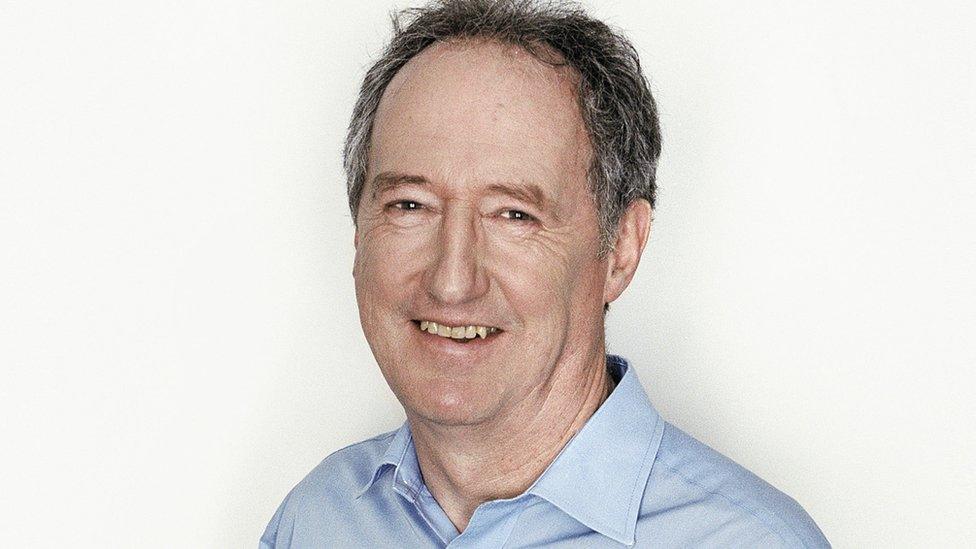

Former Radio 2 host Simon Mayo described the star salaries' publication as an "annual turkey shoot"

Roger Bolton was recently dropped from Radio 4's Feedback, to listeners' (and his own) disappointment. But he said he understood the need to freshen schedules and attract younger audiences.

"It would be criminal if you inherited Radio 2 or Radio 4 and you let it wither," he told BBC News earlier this week. "So they have a responsibility. Now, how they do it, who they choose, when they choose - that's where the argument comes. But that they have to try is an undoubted factor, I think. It's tough."

Radio listeners are famously resistant to change, and often sceptical that it's even possible to attract young audiences to stations that skew older. After Bolton's exit, one tweeted: "This is exactly what's wrong in the BBC. No young people are going to listen to Feedback, even if you get HRVY or Joe Sugg to present it, because BBC Radio 4 isn't on their radars."

Schedule changes are also sometimes made, controversially, for reasons of diversity. In 2018, the BBC forced Mayo to share his hugely popular Drivetime show with Jo Whiley, to get a female presenter on the Radio 2 daytime schedule.

The resulting show was a disaster, and Mayo left for Bauer, where he currently presents on Greatest Hits Radio. He continued hosting his film show on Radio 5 Live with Mark Kermode, but that was recently poached too, by Sony.

Vanessa Feltz (pictured with partner Ben Ofoedu) waved goodbye to the BBC for a new job at Talk TV

For some, however, no amount of money or freedom would be enough to compensate for the drop in relevance or audience that sometimes comes with leaving. When Chris Evans swapped Radio 2 for Virgin, he went from having around nine million listeners to around one million.

"What the BBC does have is an unrivalled platform," says Kanter. "I spoke to a well-known BBC radio presenter recently, who was offered a lot of money to join a rival.

"This presenter weighed that offer up, but ultimately decided that the platform they have on the BBC was more compelling than the cash. They believe that when they are presenting on the BBC, they are talking to the nation."

Replacing someone audiences love is difficult, for the presenter as much as fans. "We must remember we are talking about human beings, at the end of the day, who want to stay in a job they enjoy doing, who are experienced and talented in their field," notes North.

"So it's difficult to say to anyone in a job they enjoy that it's time for them to go - especially if the reasons are not explained. But at the same time, presenter paranoia exists for a reason - we're all aware there's always somebody behind you wanting to do your job."

Related topics

- Published31 August 2022

- Published29 August 2022

- Published1 July 2022

- Published15 August 2022

- Published26 August 2022

- Published11 March 2022

- Published19 December 2020