Eurovision 2023: The man who made a living betting his house on a song

- Published

Daniel had been a professional Eurovision gambler for nearly a decade

Are you tempted to bet on the outcome of Eurovision? One man made a living out of taking such gambles, betting his home as collateral… until the year his luck seemed to run out.

For many viewers, the best part of Eurovision is the voting. Douze points! Nul points! But can you imagine if the result decided whether you won tens of thousands of pounds - or lost your house?

That agony of anticipation faced Daniel Gould in 2018 - after he literally bet his home on the Eurovision result. As the votes piled up, just two countries were left in contention: Israel and Cyprus. Which would get the bigger televote? The next words out of the presenter's mouth seemed set to shape his life.

Daniel had been a professional Eurovision gambler for nearly a decade. Yes, you read that right.

I met him at university in the 1990s but then we fell out of touch. In my podcast, Cautionary Tales, I recently had the opportunity to catch up with Daniel's story by interviewing a mutual friend, Andrew Wright.

He told me Daniel had always been a Eurovision fan, but in 2004, he realised he could make serious money from it.

In 2009, Daniel backed Alexander Rybak's song Fairytale to win the contest

That was the year Eurovision introduced semi-finals. Daniel worked out that some countries were almost certain to get enough televote points to qualify for the final, based on diaspora votes, ie, those in other countries voting for their homeland. Think of Turks in Germany voting for Turkey, or Romanians in Italy voting for Romania.

Daniel made big bets, at short odds, on songs qualifying. He might risk something like £100,000 to win £3,000. He'd calculated these bets were practically a sure thing. But as the results were being announced, he couldn't bear to watch - he confessed he'd be "facing the wall, biting my fist".

Living his dream

The wins kept coming in. In 2009, Daniel backed Alexander Rybak's song Fairytale to win the contest. The profits paid off the mortgage on his flat in northwest London's Kentish Town. He decided to quit his job as a history teacher and go full-time as a Eurovision gambler.

For months every year, Daniel lived and breathed Eurovision - analysing trends, researching performers, tracking rumours on obscure discussion forums. He'd scrutinise the ever-shifting odds on various markets, from winner to top ten to semi-final qualifiers. He would trade these Eurovision bets like city brokers trade shares, trying to anticipate shifts in sentiment. This was no compulsive gambling - it was relentless hard work and calculation.

Every year, before Eurovision, he borrowed money against the value of his flat to trade with. Every year, after Eurovision, he paid it back again.

In a typical year, he'd win around £50,000. He'd spend it travelling the world. Daniel loved Eurovision, and he loved travel - he was living his dream.

Daniel, second left, with the Eurovision crowd in 2014 in Vienna

It isn't easy to see into the future. Philip Tetlock, a psychologist and forecasting expert, has found that the best forecasters - the "superforecasters" - spend their time weighing up many sources of conflicting information. They think in probabilities, not certainties, and are always open to new evidence. Most people find this challenging. But if you're going to bet your house on a song competition, you'd better be up for the challenge.

Daniel was. His historical knowledge helped him understand relationships among countries. His travelling honed his gut-feel for pop culture across the continent. He even wrote an article for the BBC a few years ago, on what Australia's entry to the contest might mean for the results.

He covered every angle. Watching rehearsals, he'd analyse staging and camerawork choices. After the semi-finals, he'd track which songs got traction on Google Trends, Spotify or YouTube. He'd consider the running order. Due to "recency bias", voters tend to forget songs performed early. The "contrast principle" says a fast, fun song will stand out more after several slow ballads.

Daniel was brilliant at weighing up such clues. But no professional gambler gets everything right.

Real financial disaster

Professionals can't afford to be stubborn. They have to recognise their mistakes, and act quickly to cut their losses by hedging - that is, betting on the opposite outcome. Daniel was good at that, too.

But in 2018, he found that he couldn't act quickly enough. He'd thought the song from Cyprus - Fuego, by Eleni Foureira - had no chance. For months he'd been betting against it.

Meanwhile, he'd been betting heavily on the quirky song from Israel - Toy, by Netta. He thought it was just the kind of thing the Eurovision audience would go for. When the semi-final was broadcast, Daniel realised he'd got Cyprus wrong. Viewers loved the song.

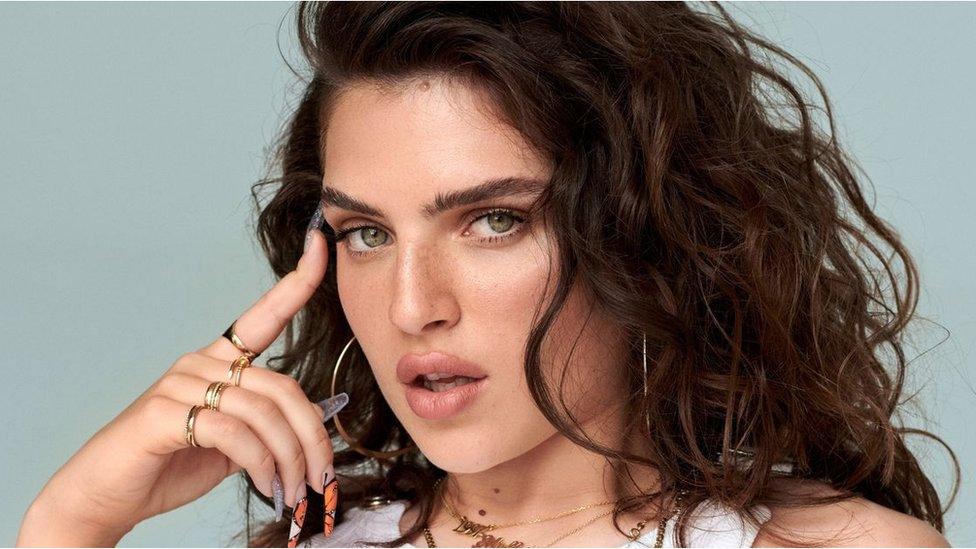

Daniel had been betting heavily on the quirky song from Israel - Toy, by Netta

Daniel went immediately into the betting markets to hedge. By betting now on Cyprus, he'd reduce his potential losses if Fuego were to win.

But Fuego had really caught fire. The odds changed too quickly for Daniel to get his bets on in time. To his horror, he was left facing a real risk of financial disaster.

In the past, when he'd had six-figure sums at risk as the results were announced, Daniel had planned those bets carefully. This was different. If Cyprus won - which now seemed gut-wrenchingly likely - he'd have to sell his flat. He watched the slowly unfolding voting process in a daze.

Eurovision aficionados among you will know how this story ends. Daniel got away with his mistake. Israel won. He could breathe again, and profited handsomely from his early call that viewers would like Netta's song. He could go off globetrotting, come back next year and do it all again.

Or so it seemed. It didn't work out like that.

Later that year, Daniel started to suffer from headaches. Then, in December 2018, while on his travels, he died suddenly - at the age of 43.

The post-mortem examination revealed he'd had a brain tumour. He'd had no idea.

Daniel always travelled to the Eurovision host city to see the two weeks of rehearsals - from Baku to Stockholm, from Kyiv to Lisbon. It was the highlight of his year. He would have loved to have been in Liverpool, watching the UK finally host Eurovision again.

As the show unfolds on Saturday, I'll be thinking of Daniel - and how, even for people who are brilliant at forecasting the future, sometimes life is just impossible to predict.

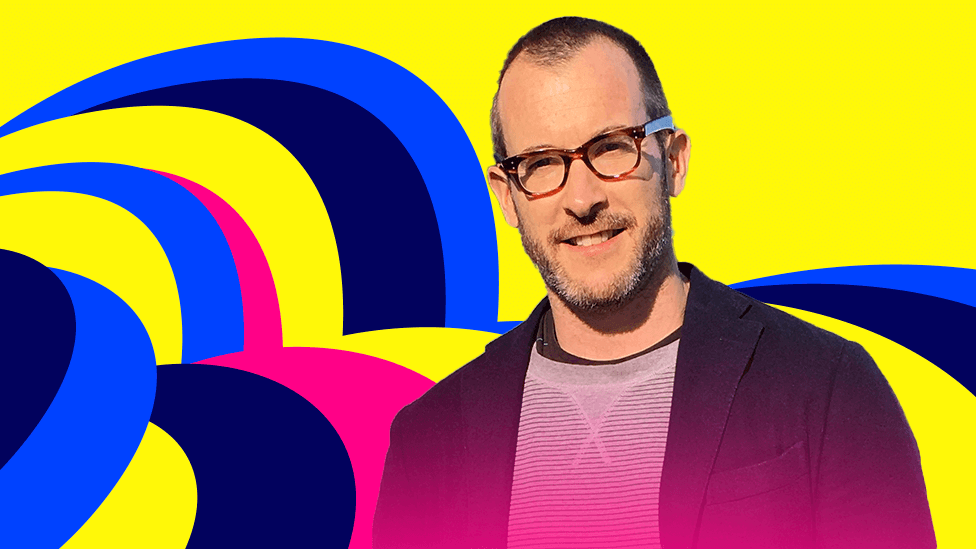

Tim Harford is a Financial Times columnist and podcaster and presents the BBC's More or Less. Cautionary Tales With Tim Harford: The Man Who Bet His House On A Song will be released as a podcast on 12th May.

Related topics

- Published12 May 2023

- Published9 March 2023