Deepfake porn documentary explores its 'life-shattering' impact

- Published

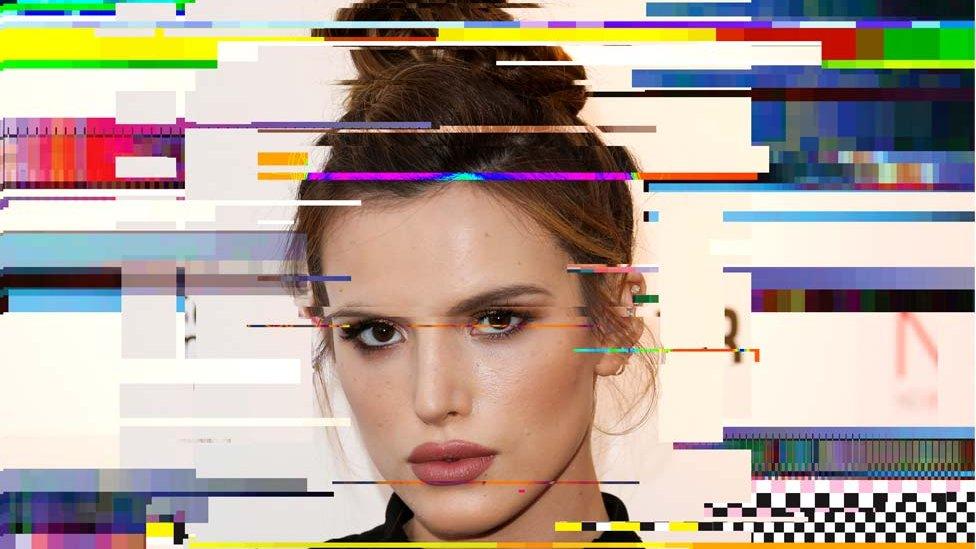

Helen Mort: "I just remember getting more and more upset... Who would want to do this?"

The director of a documentary about the impact of deepfake porn has said she hopes her film will help people understand the immeasurable trauma it causes.

Rosie Morris's film, My Blonde GF, is about what happened to writer Helen Mort when she found out photos of her face had appeared on deepfake images on a porn site.

A deepfake image is one where the face of one person is digitally added to the body of another.

Helen says in the film she thinks the pictures of her could have come from an old Facebook account, and professional shots of her in the public domain.

In the film, we see her thumbing through photos of herself aged from 19 to 32, smiling at weddings, family occasions and when she was pregnant.

These are the images which were then digitally edited onto photos of women in sexually explicit and violent scenes.

Helen Mort says she "can't unsee any of the images"

"I needed to see the pictures for myself," she says in the documentary, speaking straight to the camera. It makes the audience feel part of an uncomfortable conversation.

"There's a woman, she's sitting on the edge of the bed, she's got my face but it's not my mouth, she's [doing a sexual act]… the woman's skin is a lot more tanned than mine would be, and this woman has exactly my tattoo.

"She's looking at some text... an invitation to humiliate the person in the picture, which is me."

In the text, Helen is described as "My blonde GF", short for girlfriend, which becomes the title of the documentary.

Rosie Morris: "My film doesn't pay any attention to the perpetrator"

Morris tells the BBC she wanted to explore the impact the images had on Helen, including terrifying, graphic recurring nightmares and paranoia.

In the film, Helen says she often feels as if "people on the street somehow knew about the pictures, and they knew this horrible secret about me, which suddenly felt like my horrible secret".

This isn't the first time she has spoken about this though, and there have been other documentaries on deepfake porn, so how is Morris's film different?

"My film doesn't pay any attention to the perpetrator - I'm not interested in the headspace of the person that did it," the director says. "My main goal was I want you to walk alongside Helen in this story.

"You are with her at every stage - when I met her she was still processing it, and trying to work it out. So the only way to get you to really feel it, is if you're alongside her the whole time.

"What struck me when I met Helen was that you can sexually violate somebody without coming into any physical contact with them.

"That's the thing that motivated me."

Prof Clare McGlynn says victims of image-based sexual abuse find it "devastating"

The trauma of being used for deepfake porn is very real. Prof Clare McGlynn at Durham University, an expert in image-based sexual abuse, tells the BBC: "The impact can be life-shattering and devastating.

"Many victims describe a form of 'social rupture', where their lives are divided between 'before' and 'after' the abuse, and the abuse affecting every aspect of their lives, professional, personal, economic, health, well-being."

Helen says in the film: "I did feel as if those were real images, and it's hard to explain to someone who hasn't seen that with their own pictures, what is it really - they've done nothing to me.

"But they've planted all this stuff in my head, these pictures, I can't unsee any of the images. I can't even see the perfectly unaltered pictures in the same way either.

"I now look at that picture [an image of her in a dress] and if I saw it independently, I feel like it's a picture of an assault."

The documentary shows Helen talking about the images of herself

Morris, whose documentary was made by Sheffield-based production company Tyke Films, talks about the impact of the images on Helen.

"The most disturbing aspect is that I don't think you can separate image from memory very easily, like photographs. You know, if you look back, you don't know if you remembered the moment or you remember the photograph of it.

"So what's happened to Helen is these images, which are attached to memories, have been reappropriated, and almost planted these fake, so-called fake, memories in her mind. And you can't measure that trauma, really.

"It's like being psychologically attacked by this, it's to do with the emotional attachment to the original image."

A 2019 report says women are far more likely to face deepfake abuse

Professor Erika Rackley, from Kent Law School, tells the BBC that a few years ago she and some colleagues interviewed victim survivors of image-based sexual abuse, external.

"One of them commented in the context of deepfakes that the picture was 'still a picture of you … it's still abuse'," she says.

A 2019 report by Sensity AI, external, a company that monitors deepfakes, found that 96% were non-consensual sexual images and, of those, 99% were of women.

Prof McGlynn agrees, saying: "Women are far more likely to face this abuse, and it is mainly men perpetrating it.

"Society does not have a good record of taking crimes against women seriously, and this is also the case with deepfake porn. Online abuse is too often minimised and trivialised."

The Online Safety Bill is in the process of being scrutinised by Parliament

Helen also speaks in My Blonde GF about the unimaginable worry of not knowing who created the images.

"In every single one of those pictures it's my eyes staring at the camera," she says. "But through it all, this person, this profile creator, this image hoarder has no face."

She was even more horrified when she found that police were unable to do anything to prosecute whoever had made the images.

They told her there was nothing they could do, as no crime had been committed. It is not illegal to make deepfake images.

The law in Scotland already allows police to investigate it, but current law in England and Wales does not.

The forthcoming Online Safety Bill, external, which is currently being scrutinised in the House of Lords, is going to make sharing non-consensual deepfake porn images illegal.

Prof McGlynn says the "changes in the bill are long overdue," but for it to really be effective, "it needs to name online violence against women and girls as a priority problem, and include measures to ensure internet platforms take these abuses seriously".

The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, which is responsible for the bill, advised the BBC it is expected to become law this year.

Helen Mort has spoken several times about her experiences with deepfake porn

Morris concludes that she is "trying to ask questions" with her film, adding: "I don't have solutions, but I really feel it's something we need to pay attention to".

She says the importance of documentaries cannot be under-estimated, adding: "I think they give you a window into other people's lives.

"I feel like now, because of social media, we're so into our own experience, and how we represent ourselves.

"It's so important to think about how other people live and experience the world."

Related topics

- Published25 November 2022

- Published21 October 2022

- Published27 May 2021

- Published6 January 2021

- Published17 October 2019