Texas star Sharleen Spiteri finds magic in Muscle Shoals

- Published

Muscle Shoals, Alabama. The small town that made the big hits.

Thirty miles south of Tennessee, and two hours east of Memphis, it originally formed part of the historic Cherokee hunting grounds, but became an unlikely staging post for rock and R&B royalty in the 1960s and 70s.

Acts like Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Etta James and Paul Simon all made the pilgrimage to this backwater town, where the nicest hotel was a Holiday Inn and the restaurants served local specialties like fried catfish and turnip greens.

What drew them there was The Swampers - a crack team of studio musicians, whose rich, funky Southern grooves infused classics like Aretha Franklin's Respect, The Rolling Stones' Brown Sugar and The Staples Singers' I'll Take You There.

Part of the attraction was the town's disregard for the segregation that divided the South. The local radio station, WLAY, was unusual for playing music by both white and black artists; and the colour-blind approach was duplicated in the local recording studios.

"It was a dangerous time, but the studio was a safe haven where blacks and whites could work together in musical harmony," said Rick Hall, who owned and operated the FAME Studios from the 1950s until his death in 2018.

That gave this small, backwater town its distinctive sound: An intoxicating amalgam of gritty R&B, gospel and country, that soundtracked more than 500 singles, including 75 gold and platinum hits.

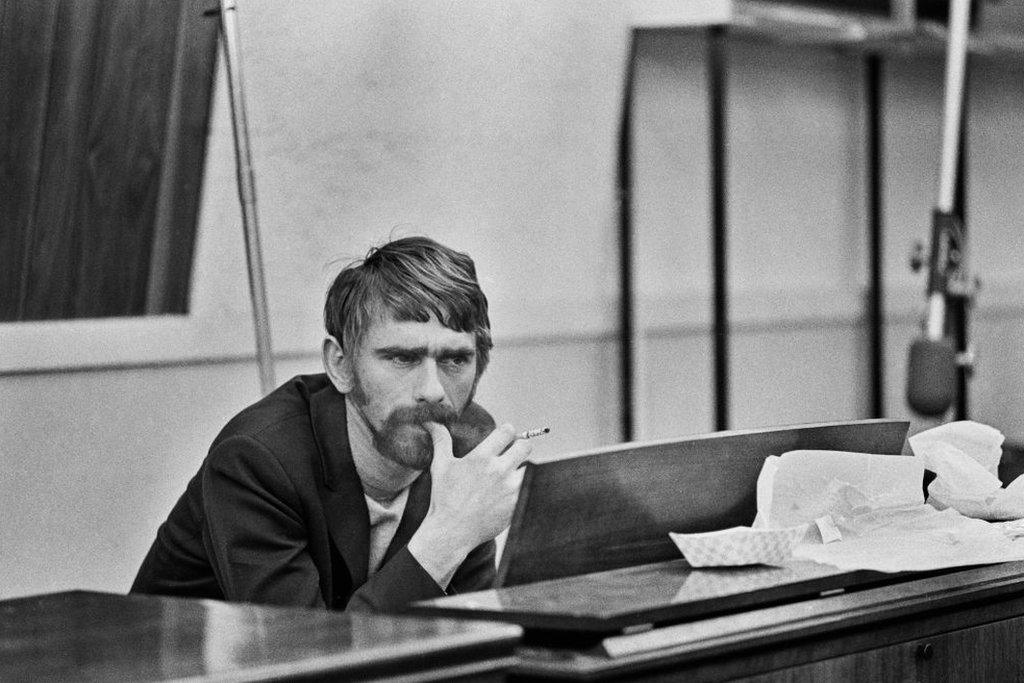

Etta James recording at Muscle Shoals' FAME Studios, circa 1967

According to former curator of Alabama's Music Hall of Fame, George Lair, the Muscle Shoals sound was a product of geography.

"You can draw a triangle from Nashville to Memphis to Muscle Shoals, and while Nashville is the country centre, Memphis is generally known as the blues centre," he told NPR in 2023, external. "Muscle Shoals, being between those two places, has been able to combine those two styles into a real Southern rhythm and blues that was very appealing."

At their peak, the Muscle Shoals' players were largely anonymous but music obsessives - the sort of people who pored over the liner notes of their vinyl albums - knew all about them: Keyboardist Barry Beckett, drummer Roger Hawkins, guitarist Jimmy Johnson, bassist David Hood and pianist Spooner Oldham.

Among those obsessives, all the way over in Balloch, Scotland, was Sharleen Spiteri, the future singer of rock band Texas.

"We all knew the story of when Aretha went to Muscle Shoals and she thought she was going to record with these old blues guys; then she turned up and it was this group of geeky white blokes," she tells the BBC.

"But when they played, she was like, 'This is what I've been looking for', and she overruled everybody and put them on her record."

So when she got the opportunity to record at FAME studios with Oldham - who'd helped Aretha shape the sound of I Never Loved A Man (The Way That I Love You) - her answer was an emphatic "yes".

"It's pretty damn special," she says. "I don't think anything's changed in the studio over the years. Inspiration is soaked into the wooden panels on the walls."

Some musicians might have been apprehensive about living up to the studio's legacy - but not her.

"I don't really get intimidated by stuff like that," she laughs.

"I'm like a peacock. My tail feather starts wagging, like, 'Oh my God, we're gonna be part of history'."

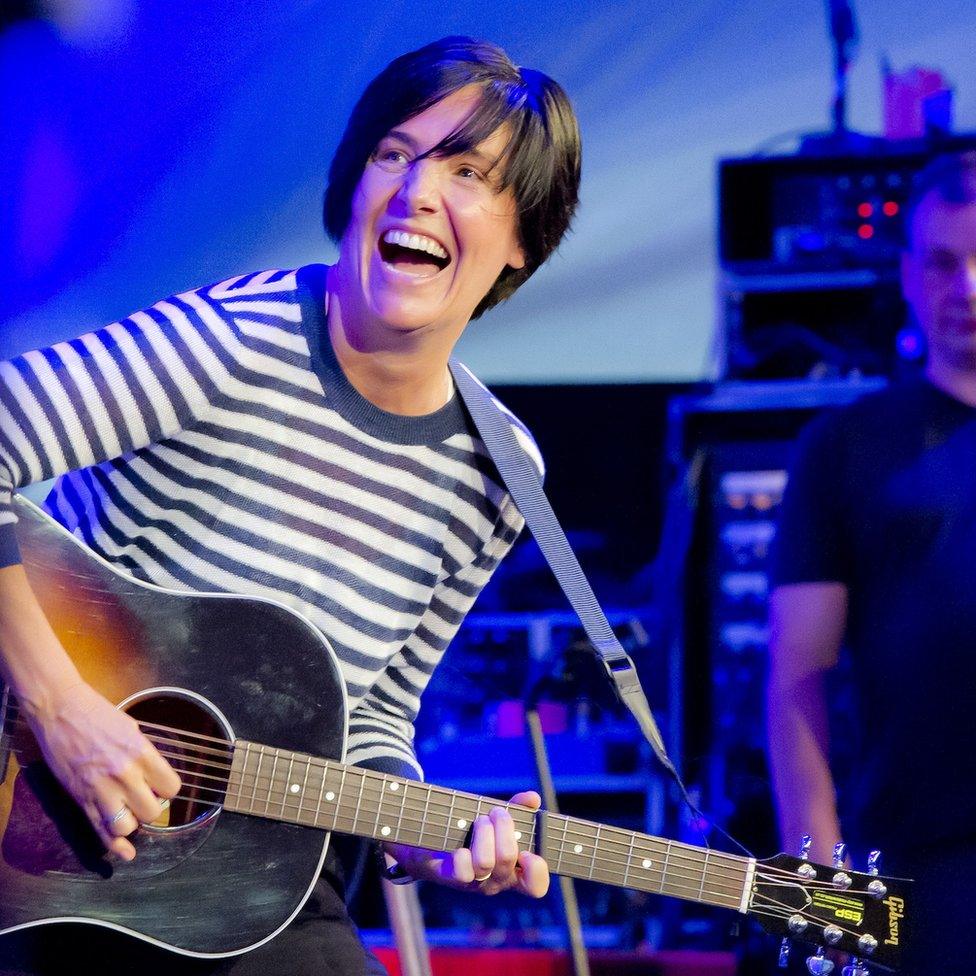

Spooner Oldham and Sharleen Spiteri recorded the bulk of the album live in the studio, in the summer of 2022

The results are gorgeous. Classic Texas songs like Halo, Say What You Want and I Don't Want A Lover are purified in the swampy waters of the Tennessee River, and reborn with a spacious, soulful clarity.

Spiteri says the tracks were laid down almost spontaneously in the summer of 2022.

"It was me sitting on the piano stool next to Spooner, tapping out the timing on his leg.

"A lot of the songs were first take, which is quite extraordinary because we didn't rehearse it.

"He'd start playing and find a certain rhythm that's not on the original [track] and suddenly we'd be dancing around each other, making new versions of a song that I thought I knew really well."

The new arrangements emphasise the sumptuous timbre of Spiteri's contralto, adding fresh intimacy to familiar melodies.

The opening track, Halo, is stripped of its pop sheen and presented as a gospel devotional, with Oldham at the organ and the backing vocalists summoning a ghostly spirituality.

"When we hit record, I was literally like, 'Holy cow'," says Spiteri. "It's so emotional, and I think you can really feel the joy in the little exchanges between us."

But before she got too carried away, reality intruded.

"The thing is, even when we were making a record at Muscle Shoals we had to stop every day at one o'clock because they had a guided tour," laughs Spiteri. "That's how they make ends meet."

Spooner Oldham has added piano and organ to recordings by Neil Young, Bob Dylan, Jackson Browne and Cat Power

It's a harsh reality of modern music. Bands rarely record live to tape any more, with most albums pieced together on laptops.

As a result, storied recording studios like Muscle Shoals and FAME are either closing or finding new ways to survive.

"It's so tight now," says Spiteri.

"You can't go to your record company and say, 'Okay, we're going to hire a 72-piece orchestra'. That's not happening unless you're Beyoncé... And this is coming from someone who actually sells records.

"Those budgets don't exist, yet record companies insist on giving all our music to streaming companies for next to nothing."

Texas were fortunate, in that they made their names during the CD era, selling almost two million copies of their 1997 album White On Blonde in the UK alone.

Still selling out arenas, they left the major label ecosystem almost two decades ago, and now release music in partnership with the more artist-friendly independent label, Pias.

Even so, Spiteri is worried about the future for songwriters.

"I personally felt the music industry should have gone out on strike with the film industry," she says, referring to last year's writers' strike, which secured increases in royalty payments for streaming content, and protections against the use of artificial intelligence in scripts.

Spiteri makes a similar argument to the screed Raye delivered at the Brit Awards earlier this month: Royalty rates are too low; and songwriters should get paid when their music is streamed (at the moment, they are not automatically entitled to anything).

Texas will play a greatest hits tour across the UK this September

"The problem is that unless the really big artists withhold their music from streaming services, nothing will change," she says.

"If the whole music industry stood together and said, 'Screw you all, none of you can have the music,' it would be very interesting to see what happens.

"It's shameful that record companies don't make a stance and protect us... But you did'nae join a band because you want to be rich and famous," she muses.

"Well, some people do, but you can sniff out the real deals."

If anyone can claim to be the real deal, it's Spiteri. No-nonsense, music-first, and utterly in command of the stage, she's been a rock star ever since she gave up hairdressing to form Texas almost 40 years ago.

Their latest album may revisit old ground, courtesy of a pilgrimage to hallowed turf - but it sounds like a band revitalised, and Spiteri can't wait to get back on stage.

"You have to go on full tilt, every night," she says. "People want to be entertained, they want a right old sing-along.

"So you can't be thinking, 'Hey, let me see how I'm feeling tonight'. That's not how it works.

"You have to put on your big boy pants and pull it off."