The world in 2017: The battle of ideas

- Published

2016 was the year of the unravelling. Norms were dispensed with. Old ideas were challenged and discarded. Our settled world was shaken and we became used to the shock of the new.

Since World War Two, and earlier, there was a consensus that trade was about much more than just economics. It was an instrument for peace. Reducing trade barriers sparked growth and prosperity. That consensus is creaking.

Global trade can boost economies but it can strip out layers of manufacturing. One of the winners from a year of political upheaval was protectionism.

Those broad signature multinational free trade deals face challenges. Donald Trump has signalled that the United States will withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement. The trend is towards bilateral deals.

Even on the left - particularly in France - voices urge the building of a strong state to protect the country from foreign interests, from globalisation.

Nationalism is back. Not in its old form but economic nationalism has resurfaced. Donald Trump has reclaimed an old isolationist slogan, America First. In trade deals, in international relations, the deciding factor will not be policing global order but serving American interests.

Donald Trump's victorious campaign revolved around "putting America first"

In the UK, campaigners in favour of leaving the EU offered voters the chance "to take back control of the country". It was UK first. In France, the centre-right politician Francois Fillon - and the man most likely to be the next resident of the Elysee Palace - has declared that "French foreign policy must serve French interests".

"Let's leave aside," he said, "the dream of a federal Europe."

Former US treasury secretary Larry Summers has spoken of a "responsible nationalism". "It starts," he says, "from the idea, that the primary responsibility of any government is to the welfare of its citizens, not to some concept of international order."

Also making a return - the strongman, the strong leader. Among Donald Trump's circle there is admiration for Putin's "strength". We are witnessing the rise of illiberal democracies. The new authoritarians pander to the desire to see order restored in a complex global world.

Alongside Vladimir Putin stands Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan and, to a lesser extent, Hungary's Viktor Orban. In the wings waits France's Marine le Pen. Some are inclined to add Donald Trump's name to the list.

What the new authoritarians share is a contempt for international organisations. Trump dismissed Nato as "obsolete" before rowing back. Putin ignores treaties that constrain him and so the international post-war structures are weakening.

Isolationism has returned. Both in the US and in Europe there is little appetite for international military campaigns. In Syria it is the Russians and, to a lesser extent, the Turks who are shaping the reality on the ground. The West is leaning inwards.

Although the European Union has retained sanctions against Russia over its actions in Ukraine, new leaders are looking to reset their relationship with Moscow.

Russia's President Putin is admired by many as a political "strongman"

However much it offends their values, the Europeans have been only too willing to strike a deal with President Erdogan of Turkey if he will reduce the flow of refugees to Europe.

It is not that the basic values that bind Europe to North America have been discarded but Western liberal democracy appears defensive and uncertain.

Recently, former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger commented that "for the first time since the end of the Second World War, the future relationship of America to the world is not fully settled".

National identity matters again. In France, Francois Fillon, the candidate of the centre-right, declares that "no, France is not a multicultural nation". In Germany, Angela Merkel insists that "we don't want any parallel societies. Our law takes precedence before tribal rules, codes of honour and Sharia."

And so, across Europe and across North America, the debate sharpens about integration.

There is a shift, a step towards encouraging assimilation, of making new migrants embrace existing liberal values. "The full veil is not appropriate," says Angela Merkel. "It should be banned wherever it's legally possible."

In Germany, enthusiasm for willkommenskultur - for a welcoming culture towards migrants, has withered. We are told that the lines of refugees heading to Germany in 2015 wont happen again.

In the United States, a central plank of the Trump campaign was a promise to move against undocumented immigrants, including a vow to "build a great, great wall on our Southern border".

Angela Merkel will stand for a fourth term as Germany's chancellor

As he prepares for office, some of Donald Trump's plans may have softened but the debate over immigration, which was a key feature of the Brexit campaign, will continue to unsettle political waters.

Trickle-down economics is back. In America, there will be tax cuts for all, including the wealthiest, in the belief that it will fire up the economy. The Trump administration is planning a massive fiscal stimulus by pumping money into rebuilding America's infrastructure. There will be a bonfire of regulations.

In Europe, too, with the calendar marked by crucial elections, the commitment to enforcing further deficit reductions will weaken.

It had been thought that the big arguments over global warming had been settled but they are in play once again. The Paris agreement committed the international community to limit the rise of global temperatures. Donald Trump has chosen as his new head of the Environmental Protection Agency a man who has questioned the science of climate change.

There will now be a huge fight for the new president's ear as to whether he pulls the US out of the Paris Agreement.

All Western governments will struggle with this question: can the state provide protection against globalisation?

Millions of people in Europe and North America have given up on established political parties because they doubt they can deliver. So far, the social democrats - the centre-left - have been unable to make insecurity and inequality their theme.

The political battle will be fought over who is best placed to help those not being lifted up by the globalised tide.

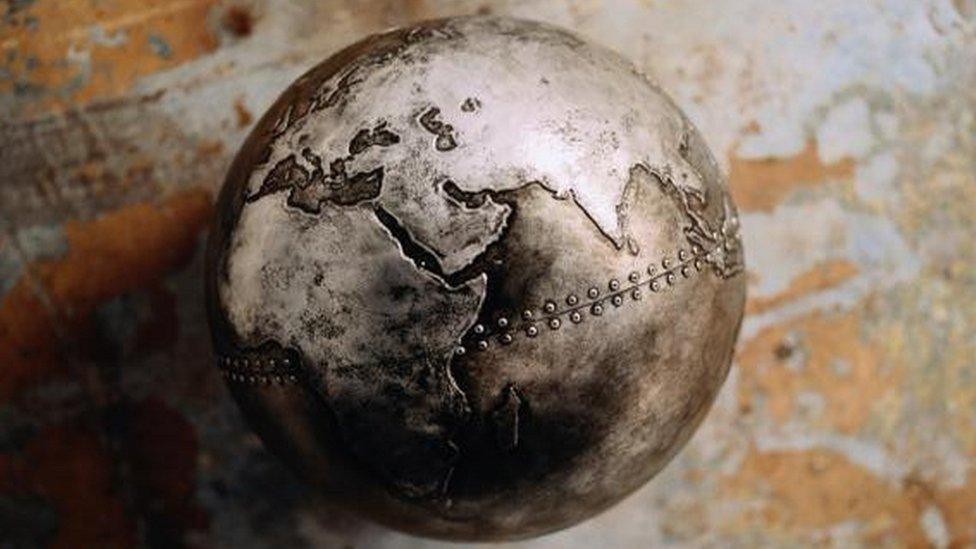

The debate about globalisation will be an important one in the coming year

The battle for voters' minds will be fought out in an era of post-truth politics, of fake news spiced with conspiracy theories. In both the UK and the US, the media has struggled with false equivalencies. Experts were dismissed.

In America, some of those close to the Trump campaign have tried to redefine truth. It is not the marshalling of facts in pursuit of an objective truth that necessarily counts, they argue. It is the fact that many people believe something, even a conspiracy, that makes it true. The media will be at the centre of this battle of ideas.

The anti-establishment campaigners believe they are winning. A senior figure in the French National Front said that the establishment's world "is collapsing. Ours is being built." Nigel Farage, the former leader of UKIP, has spoken of a "democratic revolution" that has only just begun.

Beppe Grillo from the Italian Five Star movement, says "it is the risk-takers, the stubborn, the barbarians who will carry the world forward". Many others see the barbarians at the gates of liberal democracy.

So 2017 is set for further battles between two competing visions. On the one hand are those dedicated to defending the nation state and whose instincts are to erect walls against a dangerous and unstable world. On the other, are those who believe in liberal internationalism, in openness, free trade and international institutions.

- Published30 December 2020