The birth of IVF

- Published

Nearly four million babies have been born using IVF

It was in the late 1950s that British scientists Robert Edwards first came to realise the potential of IVF (In Vitro Fertilisation) as a treatment for infertility.

The keen biologist knew from the work of others that it was possible to take an egg from an animal, like a mouse or a rabbit, and fertilise it with sperm in a test tube.

Armed with this knowledge, Edwards made it his mission to find out if the same could be done using human eggs.

Some 30 years later, his dream was realised with the birth of the world's first human test-tube baby in 1978.

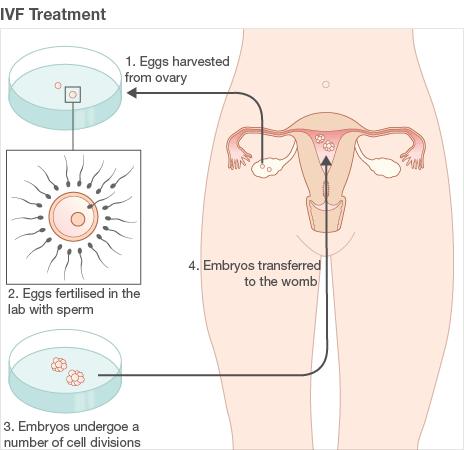

Since then nearly four million babies have been born using the technology that takes a mature egg from a woman's ovary and mixes it with sperm in the lab before implanting it into the womb.

But the journey to get to where we are today was not just long, but incredibly difficult.

First came the problem of getting the basic science to work in humans.

Edwards struggled for years to find the ideal conditions to get his test-tube fertilisation to work.

In 1969, his efforts paid off when, for the first time, a human egg was fertilized in a test tube.

In spite of this success, a major problem remained.

The fertilised egg did not develop beyond a single cell division. Edwards suspected that eggs that had matured in the ovaries before they were removed for IVF would function better, and looked at how to harvest such eggs in a safe way.

He teamed up with gynaecologist Patrick Steptoe and together they developed a technique that would, eventually, lead to the modern IVF used today.

But despite promising early studies, the pair hit another setback - a lack of financial backing to move their pioneering work on.

After being rejected funding from the Medical Research Council, the team were forced to find a private donation.

Creating a stir

Even with this secured, they faced another problem. Their research had become the topic of a lively ethical debate, with several religious leaders, ethicists, and scientists demanding that the project be stopped.

Rather than shy away from the issue, Edwards tackled it head-on and created an ethics committee for IVF at the Bourn Hall Clinic he then set up with Steptoe in Cambridge.

Looking back at this time he said: "The most important thing in life is having a child.

"Nothing is more special than a child.

"Steptoe and I were deeply affected by the desperation felt by couples who so wanted to have children.

"We had a lot of critics but we fought like hell for our patients."

The pair got back to work and in the early 1970s they started to transfer their early IVF embryos back into women.

After more than 100 attempts that all led to short-lived pregnancies, they tweaked their design and in 1978, they offered their new treatment to a couple called Lesley and John Brown who came to the clinic after nine years of failed attempts to have a child.

Nine months later, a healthy baby, Louise Joy Brown, was born through Caesarian section after a full-term pregnancy, on 25 July, 1978.

IVF had moved from vision to reality and a new era in medicine had begun.

Fruits of labour

Edwards and Steptoe continued working together at their clinic - the world's first IVF centre - teaching other doctors how to carry out the procedure.

By 1986, 1,000 children had already been born following IVF at Bourn Hall, representing about half of all children born after IVF in the world at that time.

The pair worked together until Steptoe died in 1988. Edwards then continued as head of research until his retirement.

Their achievements attracted many other researchers to the field of fertility medicine which has led to rapid technical development.

IVF has now been joined by other revolutionary fertility treatments like intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), which makes it possible to also to treat many categories of male infertility, and preimplantation genetic diagnostics (PGD), which helps reduce the risk that parents can pass a severe genetic disorder or a chromosomal abnormality to their children.

And today, 2-3% of all newborns in many countries are conceived with the help of IVF.

- Published4 October 2010