Brain cancer 'trojan attack' hope

- Published

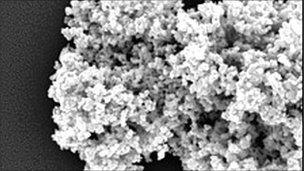

Nanoparticles are 1,000-times smaller than the width of a human hair

A tiny capsule could help smuggle anti-cancer drugs past a barrier designed to protect the brain from attack.

The "nanocarrier" containing the drug was tested on tumours in mice, and proved better at reducing them than the drug alone.

A conference in Berlin was told that the method could also cut the side-effects of powerful medication.

Cancer drugs which could reach the brain are urgently needed, say UK experts.

The 'blood brain barrier' is a defence system designed to protect the sensitive brain from large, potentially toxic molecules circulating in the blood.

However, this function means it ends up protecting cancer cells in the brain from drugs.

Trigger

The researchers from Germany's Max-Delbruck Centre for Molecular Medicine have tried to hijack the barrier's own mechanisms to help get the drugs through.

Molecules which are needed by the brain activate receptors at the barrier, and are actively pulled through.

The team found a molecule which could trigger this process, and constructed a capsule containing the drug mitoxantrone, with this molecule attached to its surface.

The disguise appeared to work, at least in mice with breast tumours implanted into their brains.

In comparison with untreated mice, the "nanocarrier" mitoxantrone reduced tumour area by 73%, and more importantly, by 45% in comparison with mice simply given the drug on its own.

Also, the researchers noted the extent of side-effects in the mice.

While those given only the drug had weight loss, dehydration, and stomach disorders, there were no noticeable side effects in those given the nanocarrier treatment.

This, they said, was because the molecule on the surface of the liposome capsule marked it for delivery to brain cells, stopping it from wreaking havoc in other parts of the body.

Andrea Orthmann, one of the researchers, said the "nanocarrier" could potentially hold not only other cancer drugs, but also drugs aimed at other brain conditions.

She said: "The liposomes have the potential to be used in several other diseases, including neurodegenerative ones such as Alzheimer's Parkinson's and Huntingdon's disease, as well as other tumours."

However, she conceded that much more time-consuming work would be needed before the technology could be used in humans.

Roy Rampling, professor emeritus at Glasgow University and a specialist in neuro-oncology, said that other researchers in the UK and abroad were using similar approaches.

He said: "The idea is to encapsulate drugs to deliver their payload once they reach the brain.

"You need to get sufficient drug into the brain without increasing side-effects, and because it is encapsulated, it doesn't produce the same level of toxicity in other organs, particularly the bone marrow."

Trevor Lawson, from Brain Tumour UK, which supports similar projects, said that there was an urgent need to find new ways to deliver drugs across the blood brain barrier.

He said: "In addition to the terrible impact of primary tumours in the brain, which claim more children and adults under 45 than any other cancer, there are already reports that secondary brain cancer is increasing as we get better at treating cancer elsewhere in the body.

"Some oncologists predict that the brain will be the final battleground against cancer, so drugs developed at this nano-molecular level will be an essential weapon."

- Published19 October 2010