Children are at risk of getting rickets, says doctor

- Published

- comments

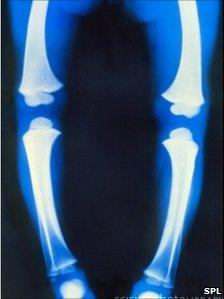

X Ray of a child's legs with rickets

We are all aware of the dangers of too much sun, especially for children. But has the safe sun message inadvertently created vitamin D deficiencies, resulting in a resurgence in rickets?

In this week's Scrubbing Up, orthopaedic expert Dr Joe Reed - who is based at Southampton Hospital - says the Department of Health needs to do more to make parents and doctors more aware of the dangers of not enough sun.

I recently watched families - wrapped head to toe in multiple layers - make the most of some Sunday afternoon winter sun.

However, my enjoyment was slightly capped by the concern in the back of my mind that, despite beautiful days like these, childhood rickets in the UK is back.

Tiny Tim

Rickets - childhood vitamin D deficiency resulting in skeletal pains or bony deformities - was, until recently, thought to be a thing of the past in our developed society and historically associated with poverty-stricken communities or fictional characters such as Tiny Tim from Dickens' A Christmas Carol.

At Southampton General Hospital, we have recently uncovered evidence to suggest a resurgence of vitamin D deficiency amongst children.

Our study has shown that this is not confined to the lower classes or ethnic minorities, with those from the leafy suburbs and coastal towns just as likely to be affected.

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble compound essential for bone growth and mineralisation during childhood.

It is produced in the skin following exposure to ultraviolet B light with a small amount occurring naturally in foods such as oily fish, eggs and meat.

Without vitamin D the body is unable to effectively process the minerals calcium and phosphorous; essential for bone growth and maturation during childhood.

Bone deformities

Vitamin D deficiency is a major factor in the development of bone deformities including rickets, genu valgum ("knock knees"), genu varum ("bowed legs") and non-specific musculoskeletal pain in children.

Those with severe skeletal deformities are faced with the prospect of long and painful corrective surgical procedures.

Alarmingly, our figures suggest that up to 40% of children presenting to the orthopaedic outpatient service in Southampton have vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency

But with a little knowledge, these conditions are avoidable.

Both the general public and GPs need to be more aware of the dangers of vitamin D deficiency and the benefits that a little sunshine can bring.

Fifteen minutes of sunshine per day at 3pm is nothing to be feared.

We need sunshine to make vitamin D and GPs need to be aware of the initial symptoms of a deficiency.

This means knowing that a young person presenting with bone aches and pains could be deficient and may benefit from a blood test and perhaps referral to an orthopaedic clinic.

Raising awareness

Parents need to be aware that always covering up in the sun and not allowing their children to get a moderate amount of sunshine can lead to problems too.

In both cases, the Department of Health has a role to play in raising awareness. A health campaign to advise both doctors and the public of the benefits of sunshine could help with preventing surgery later.

There is a dearth of strategies in place to deal with vitamin D deficiency and previous initiatives have been inadequate.

The "Healthy Start" scheme, implemented in 2006, targeted the economically disadvantaged with supplements given to children only from very low-income families. Clearly, in light of our recent finding, this is hugely inadequate.

Several theories have been postulated to explain the increase in vitamin D deficiency.

Lack of sunlight is thought to be a major factor, with intentional avoidance and the use of sunscreen due to concerns of skin cancer risk.

In addition, the youth of today are increasingly choosing to substitute outdoor pursuits for indoor activities such as internet social networking and texting and far more commonly, children are being driven to school on a daily basis instead of a good half-hour or so walk.

Worryingly, here we present evidence for an increase in a potentially reversible factor, contributing to significant morbidity in children, yet no effective methods are in place to treat vitamin D deficiency in the UK population.

Clearly, there is an urgent need to reassess the Department of Health strategy in this area. Targeting all at-risk children with vitamin D supplements could be one way.

We are not merely trying to scare or relay the grim reality that a 19th Century epidemic is back, but offering optimism and a cost effective solution to what could potentially expand into a public health crisis.