Haiti cholera 'far worse than expected', experts fear

- Published

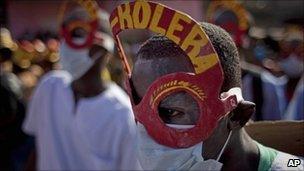

Cholera is killing thousands in Haiti

The cholera epidemic affecting Haiti looks set to be far worse than officials had thought, experts fear.

Rather than affecting a predicted 400,000 people, the diarrhoeal disease could strike nearly twice as many as this, latest estimates suggest.

Aid efforts will need ramping up, US researchers told The Lancet journal.

The World Health Organization says everything possible is being done to contain the disease and warns that modelling estimates can be inaccurate.

Before last year's devastating earthquake in the Caribbean nation, no cases of cholera had been seen on Haiti for more than a century.

The bacterial disease is spread from person-to-person through contaminated food and water.

It causes severe diarrhoea and vomiting, and patients, particularly children and the elderly, are vulnerable to dangerous dehydration as a result.

Gross underestimate

In the three months between October and December 2010, about 150,000 people in Haiti contracted cholera and about 3,500 died.

Around this time, the United Nations projected that the total number infected would likely rise to 400,000.

But researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, say this is a gross underestimate, external.

They believe the toll could reach 779,000, with 11,100 deaths by the end of November 2011.

Dr Sanjay Basu and colleagues reached their figures using data from Haiti's ministry of health.

They say the UN estimates were "crude" and based on "a simple assumption" that the disease would infect a set portion (2-4%) of Haiti's 10 million population.

Dr Basu's calculations take into account factors like which water supplies have been contaminated and how much immunity the population has to the disease.

They predict the number of cholera cases will be substantially higher than official estimates.

"The epidemic is not likely to be short-term," said Dr Basu. "It is going to be larger than predicted in terms of sheer numbers and will last far longer than the initial projections."

But the researchers say thousands of lives could be saved by provision of clean water, vaccination and expanded access to antibiotics.

A spokesman for the World Health Organization said: "We have to be cautious because modelling does not necessarily reflect what's seen on the ground.

"Latest figures show there have been 252,640 cases and 4,672 deaths as of 10 March 2011.

"We really need to reconstruct water and sanitation systems for the cholera epidemic to go away completely.

"It's a long-term process and cholera is going to be around for a number of years yet."

- Published14 February 2011

- Published12 January 2011