Cholera pandemic has a single global source

- Published

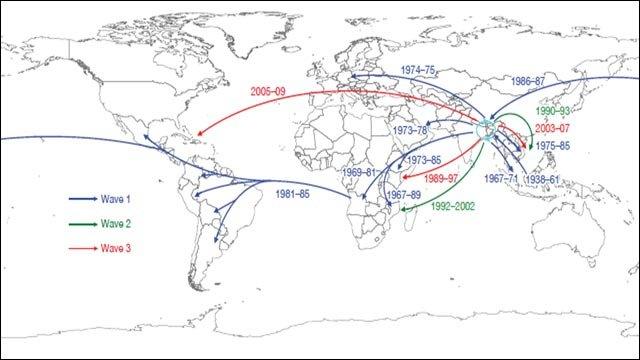

How cholera has spread from the Bay of Bengal

A major cholera pandemic has spread in at least three waves from a single global source: the Bay of Bengal.

A study in Nature, external reveals cholera's spread over the last 60 years into Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas, continent-hopping on long-haul flights.

The research by a team from Cambridge's Sanger Institute showed the infection is evolving, with the newest waves showing antibiotic resistance.

A UK expert said it was "a scandal" cholera was still affecting people.

Cholera is a bacterial infection of the intestine that causes diarrhoea. It affects 3-5m people annually in 56 countries, killing between100,000 and 150,000.

If untreated, it can kill within hours through dehydration. It is easily treated by drinking clean water, but without this, severe cases have a 30-50% mortality rate.

'Only explanation'

In this study, the researchers sequenced the genome of 154 samples collected from patients around the world. Genome sequencing technologies have been getting better, faster and cheaper. Until recently, sequencing would be carried out on just four or five bacteria samples.

The ecology and climate of the Bay of Benghal could be why cholera has spread from there

Similarities between cholera genomes showed how the various strains are related, while subtle differences showed how it is evolving.

By investigating these bacteria at the genetic level, the authors were able to piece together the story of the latest, and ongoing, global cholera pandemic.

"We were surprised to see that the pattern we see is very clear. All of the samples were related. There is a single global source of cholera in the Bay of Bengal," said co-author Dr Nick Thomson of the Sanger Institute.

It is not yet clear why the Bay of Bengal is at the centre of the pandemic, though cholera bacteria exist naturally within some marine ecosystems.

The local ecology, climate, and the presence of large river deltas are likely to be key factors in its presence there.

The results show several cases of cholera suddenly jumping between continents, suggesting that it was spread by passengers on long-haul flights.

"I think that's the only possible explanation. Our data show that this has happened, for example from Angola to South America.

"Many people can have cholera with no symptoms, so they transmit it without realising," added Dr Thomson.

'One fell swoop'

The most recent outbreak is in Haiti where it took hold shortly after the 2010 earthquake after being absent for more than a century.

So far it has killed nearly 6,000 people and hospitalised 200,000.

A recent report by the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention linked this outbreak to the arrival of UN troops from Nepal, a finding supported by this study. In November 2010, the UN issued an appeal for $160m to fight the spread of the cholera in Haiti.

Another worrying pattern emerged from the genome analysis. Three waves of cholera have come out of the Bay of Bengal since the 1950s, and from the second wave onwards, all of the strains were antibiotic resistant.

That means that the resistance was acquired within 15 years of the first clinical use of antibiotics tetracycline and furazolidone for cholera treatment.

Dr Thompson said: "I'm not surprised it happened so fast. We think that antibiotic resistance moves between strains, and in one fell swoop a strain can become multi-resistant."

"Antibiotics are clearly one of the major driving forces in cholera evolution. However, in general antibiotics just reduce the length of infection in people."

Dr Valerie Curtis of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine said: "It's an appalling scandal that in the 21st century people are still suffering from this ancient disease.

"Cholera is symptomatic of countries where something has gone badly wrong, where the infrastructure of sanitation and clean water has broken down. This is really about poverty.

"What this study shows is that it's easy for pockets of poverty in Africa to affect pockets of poverty in the Americas, for example. It's almost impossible to stop the spread of such diseases but what we must do is invest in the public health of poor countries."

- Published7 November 2010