Malaria vaccine hope after blood entry route discovered

- Published

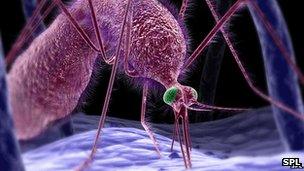

Malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes

The route all strains of the most deadly malaria parasite use to enter red blood cells has been identified by researchers at the Sanger Institute in Cambridge.

The scientists involved said the finding offered "great hope" for the development of a vaccine, which had the potential to be hugely effective.

Other experts said they were surprised and impressed.

Malaria affects 300 million people each year.

One million die, mostly children in sub-Saharan Africa.

There are many malaria parasites. Plasmodium falciparum is the most deadly and researchers at the Sanger Institute acknowledge it as a "very complex and cunning foe".

It is exceptionally good at evading and bamboozling the immune system. Within five minutes of being bitten by a malaria-carrying mosquito, the parasite is already hiding inside the liver.

It then emerges from the liver at a different stage in its life cycle and infects red blood cells, where it starts reproducing.

Difficulty

The human immune system struggles to build up resistance to malaria and researchers have struggled in the laboratory.

There is still no approved vaccine against malaria. Large scale trials of the most advanced prototype - RTS,S - showed it halved the risk of getting malaria, external.

The parasite reproduces in red blood cells (infected cell on the right).

This study, published in Nature, external, looked at the moment the parasite infected a red blood cell.

They were looking for proteins on the surface of Plasmodium and red blood cells which were necessary for the parasite to identify its target and invade.

Others had been found before, but none were universally used.

The team at the Sanger Institute discovered that "basigin", a receptor on the surface on red blood cells, and "PfRh5", a protein on the parasite, were crucial.

In all strains of Plasmodium falciparum tested so far, interrupting the link protected the blood cells from attack.

One of the researchers, Dr Julian Rayner, said: "We were able to completely block invasion using multiple different methods, using antibodies targeting this interaction we could stop all invasion of red blood cells.

"It seems to be essential for invasion."

The plan is to develop a vaccine which will prime the immune system to attack PfRh5 on the parasite

Fellow researcher Dr Gavin Wright said a vaccine would have great potential as the target was so essential.

"As a starting point for developing a vaccine you couldn't hope for better," he said.

Prof Adrian Hill, director of the Jenner Institute at Oxford University, said that after 25 years studying malaria he was "surprised" and "intrigued" by the findings.

He said textbooks and academic research suggested that if you blocked one pathway into the red blood cells, the parasite would choose another.

He added: "It remains to be seen how easy it will be to translate into a vaccine, but [for blood stage vaccines] PfRh5 is now at the top of the list.

"Vaccine candidates will come. If I had to bet, I'd say you'd get some partial efficacy from it."

- Published18 October 2011

- Published18 October 2011

- Published16 November 2010