Haemophilia gene therapy shows early success

- Published

People with haemophilia B have a faulty gene which means they cannot produce a protein to clot the blood

Just one injection could be enough to mean people with haemophilia B no longer need medication, according to an early study in the UK and the US.

Six patients were given a virus that infects the body with the blueprints needed to produce blood-clotting proteins. Four of them could then stop taking their drugs.

Doctors said the gene therapy was "potentially life-changing".

Other researchers have described it as a "truly a landmark study."

People with haemophilia B have an error in their genetic code, which means they cannot produce a protein called factor IX, which is critical for blood-clotting.

Patients are currently treated with factor IX injections, sometimes multiple times per week, but the manufacturing process is expensive.

Researchers at University College London and St Jude Children's Research Hospital in the US were looking for a more permanent solution.

Virus modification

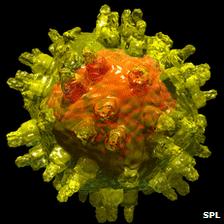

They took a virus which infects people without symptoms - adeno-associated virus eight. It was then modified to infect liver cells with the genetic material for factor IX. The gene should then persist in the liver cells, telling the cells to manufacture the protein.

Six people were injected with the modified virus at the Royal Free Hospital in London. Two were given a low dose, two a middle dose and two a high level.

An adeno-associated virus was modified to infect cells with the correct gene

Results published in the New England Journal of Medicine, external showed levels of factor IX could be increased.

Normally, patients will have factor IX levels less than 1% of those found in people without haemophilia.

After injection, levels of factor IX ranged from 2% to 12%. The first patient treated has maintained levels of 2% for more than 16 months. One of the patients receiving the highest dose maintained levels which fluctuated between 8% and 12% for 20 weeks.

Carl Walker, aged 26 and from Berkshire, showed the greatest improvement. He said: "I have not needed any of my normal treatment, either preventative or on-demand as a result of an injury. Previously, I used to infuse at home three times a week.

"I play football, run and take part in triathlons - and previously I might have had to infuse both before I took part and possibly after as well. Not having to do that has been absolutely brilliant."

Dr Amit Nathwani from University College London told the BBC that patients with 12% of normal factor IX production would no longer be seen in the clinic.

"They would be able to go about their normal daily lives without any problems. The only time that they would have a problem is if they were involved in a road traffic accident or had a big fall from a building site. In the absence of severe major trauma these individuals would not know that they have haemophilia."

He said the aim of the research was to take patients from a severe form of haemophilia to a mild one.

'Fantastic start'

"All the patients have actually benefited from this gene transfer approach, even the patients who have not been able to stop protein concentrate infusion [normal therapy]."

He said these people needed fewer injections of factor IX.

"This is the first study that has shown that you can actually achieve stable, long-term, therapeutic level of expression [factor IX production] in subjects with severe haemophilia B, so it's a fantastic start.

"This is a great breakthrough, this is the first time that anybody has been able to show that."

The trial was designed to test the safety of the procedure. Trials in more patients will be needed to fully determine its effectiveness and patients will need to be followed for longer periods of time to see how long the effect lasts.

There was an immune response against the infected liver cells around seven to nine weeks after the virus was injected. In the trial it was controlled with steroids, but doctors will also want to see if they can avoid it happening.

Dr Katherine Ponder, from the Washington University School of Medicine, said this was "truly a landmark study, since it is the first to achieve long-term expression of a blood protein at therapeutically relevant levels".

She added: "If further studies determine that this approach is safe, it may replace the cumbersome and expensive protein therapy currently used for patients."

Chris James, chief executive of the Haemophilia Society, said: "The society is delighted to see world-class research in the UK which may ultimately provide therapies to improve the life of those with haemophilia showing such positive results at this stage.

"These are early days and all medical and scientific developments need to go through extensive testing for efficacy and side effects. As such we would not wish to raise false hopes at this stage. However, we hope that this research will eventually result in the removal of the need for regular injections and significantly reduce painful bleeds and debilitating joint damage for those living with haemophilia."

- Published13 October 2011

- Published27 October 2011