'We want to prevent people getting dementia'

- Published

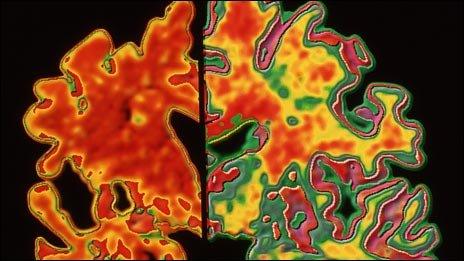

The brain of an Alzheimer's patient on the left is shrunken compared with a healthy brain

Noticing an elderly relative is suddenly starting to forget things, is getting confused or displaying sudden changes of mood are usually the first signs they are developing dementia.

But what if the disease could be spotted - and treatment given - years before any symptoms begin?

That's the aim of researchers coming together in a new centre at University College London.

Dementia is the sixth leading cause of death in the UK, and a major cause of disability. Those affected often have to move into residential care.

About 750,000 people are currently affected, and that is set to rise to a million by 2021.

The research team will look at neurodegenerative diseases - including Alzheimer's disease, as well as Parkinson's disease and less common but equally devastating conditions such as Huntington's disease and Motor Neurone Disease.

Early detection

Prof Nick Fox, of the UCL's Institute of Neurology, is one of the experts involved.

He says: "The highest priority for patients with neurodegenerative diseases is to find treatments that slow or halt disease progression.

"These treatments must then be offered as early as possible, when the minimum of irretrievable neuronal loss has occurred, in order to have maximum impact on loss of cognitive and neurological function.

"There is increasing recognition in the field that the most effective therapies will be those applied in the very earliest stages of disease."

He added: "One in four 75-year-olds already have evidence of Alzheimer's proteins in their brain, even though there's nothing wrong with them.

"And it's known that the signs appear 10-15 years before the symptoms."

Prof Fox said that current therapies and research tended to focus on when the patient was already affected.

"This will be the first of its kind neurodegenerative disease centre in Europe specifically looking for preventative treatment."

The first trial planned at the centre, which is funded by a £20m grant from the Wolfson Foundation, will look at people who have familial Alzheimer's, who are at risk of developing the disease in their 40s and 50s.

'Leading edge'

The team will carry out brain scans to see if any of the recognised early changes are seen. Further scans will then be carried out to check if anything changes.

"If you look at advances in cancer and HIV, they've been achieved by picking people up early. We want to try and take the same approach.

"We know there's this therapeutic window which has opened up. That's something we really need to capitalise on."

The researchers will also be able to collaborate on looking into treatments in a way that hasn't been possible before - and see what neurodegenerative diseases have in common.

Sir Robert Naylor, chief executive of University College London Hospitals, said: "This will allow us to work at the leading edge of translating scientific discovery into routine patient treatments."

Prof Clive Ballard, director of research at the Alzheimer's Society, welcomed the focus and investment for dementia research.

"The area is desperately underfunded and currently receives eight times less funding than cancer research.

"It's this type of initiative which will drive forward dementia research and help find a cure for tomorrow."

- Published7 November 2011

- Published23 June 2011

- Published14 April 2011