Analysis: Defeating polio

- Published

Polio vaccination in Afghanistan, one of three endemic countries

Fifty-five cases. That's all the cases of polio that have been reported in the world so far this year. A lower total for mid-May than ever before.

It hardly seems like it needs a shift to "emergency mode", as has been declared this week.

The concern is that polio, once one of the most dreaded infections in the world, could return.

After more than two decades of outstanding progress towards eliminating polio, the fear is that efforts could stumble so close to the finishing line.

Polio is capable of causing crippling disability or death within hours.

It plagued societies in ancient times - and was present in more than a hundred countries even in the 1980s, when it left 350,000 people paralysed each year.

Poliomyelitis has existed as long as human society, but became a major public health issue in late Victorian times with major epidemics in Europe and the United States. The disease, which causes spinal and respiratory paralysis, can kill and remains incurable but vaccines have assisted in its almost total eradication today.

This Egyptian stele (an upright stone carving) dating from 1403-1365BC shows a priest with a walking stick and foot, deformities characteristic of polio. The disease was given its first clinical description in 1789 by the British physician Michael Underwood, and recognised as a condition by Jakob Heine in 1840. The first modern epidemics were fuelled by the growth of cities after the industrial revolution.

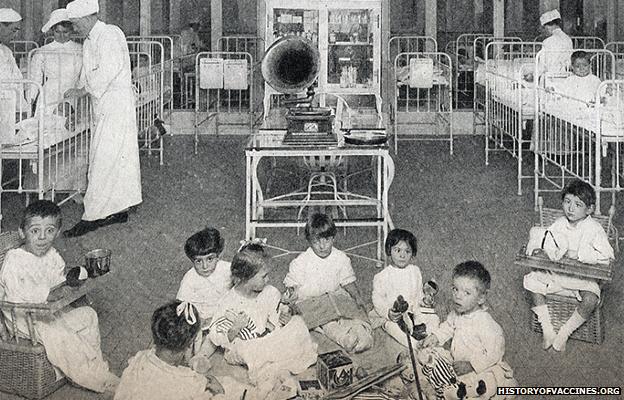

In 1916, New York experienced the first large epidemic, with more than 9,000 cases and 2,343 deaths. The 1916 toll nationwide was 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths. Children were particularly affected; the image shows child patients suffering from eye paralysis. Major outbreaks became more frequent during the century: in 1952, the US saw a record 57,628 cases.

In 1928, Philip Drinker and Louie Shaw developed the "iron lung" to save the lives of those left paralysed by polio and unable to breathe. Most patients would spend around two weeks in the device, but those left permanently paralysed faced a lifetime of confinement. By 1939, around 1,000 were in use in the US. Today, the iron lung is all but gone, made redundant by vaccinations and modern mechanical ventilators.

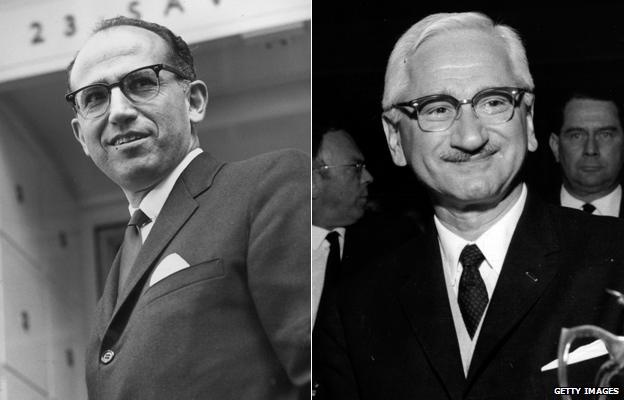

A major breakthrough came in 1952 when Dr Jonas Salk (L) began to develop the first effective vaccine against polio. Mass public vaccination programmes followed and had an immediate effect; in the US alone cases fell from 35,000 in 1953 to 5,300 in 1957. In 1961, Albert Sabin (R) pioneered the more easily administered oral polio vaccine (OPV).

Despite the availability of vaccines polio remained a threat, with 707 acute cases and 79 deaths in the UK as late as 1961. In 1962, Britain switched to Sabin's OPV vaccine, in line with most countries in the developed world. There have been no domestically acquired cases of the disease in the UK since 1982.

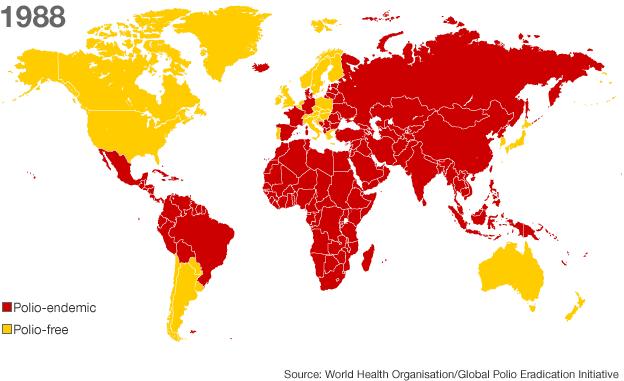

By 1988, polio had disappeared from the US, UK, Australia and much of Europe but remained prevalent in more than 125 countries. The same year, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution to eradicate the disease completely by the year 2000.

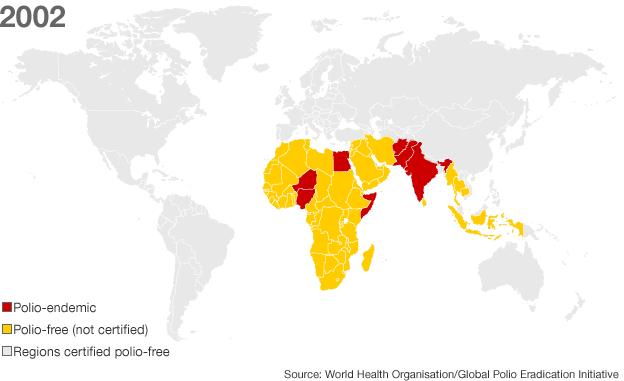

The WHO Americas region was certified polio free in 1994, with the last wild case recorded in the Western Pacific region (which includes China) in 1997. A further landmark came in 2002, when the WHO certified the European region polio-free.

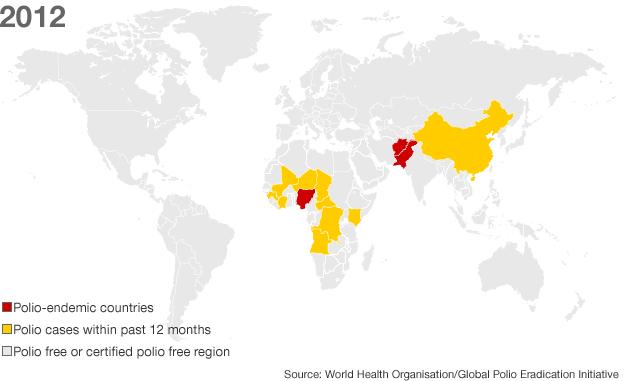

In 2012, Polio remains officially endemic in three countries - Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan. Despite so much progress, polio remains a risk with virus from Pakistan re-infecting China in 2011, which had been polio free for more than a decade.

Stubborn

Cases of polio have fallen by more than 99% since the Global Polio Eradication Initiative started in 1988. All that remains is a stubborn 1%.

Three countries are now at the heart of concern: Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan. They are the only countries where polio is endemic. Cases in other countries spread from here.

Within those three countries, the figures are worrying some. Between 2010 and 2011, cases in Afghanistan increased by 220%, in Nigeria by 185% and by 37% in Pakistan, which was responsible for a third of all cases in the world.

It is easy to understand how a combination of conflict, politics, poor resources and difficult terrain combine to make a vaccination programme difficult.

Last week the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon poetically described the threat of polio, external.

"Wild viruses and wildfires have two things in common. If neglected, they can spread out of control. If handled properly, they can be stamped out for good.

"Today, the flame of polio is near extinction - but sparks in three countries threaten to ignite a global blaze."

There might not be a global blaze, but there has certainly been smoke on the horizon.

China had its first outbreak of polio for the first time in more than 10 years in 2011. The virus spread to Xinjiang province from bordering Pakistan.

A large outbreak stemming from Nigeria, external affected 24 countries in west and central Africa at the end of the last decade and there have been outbreaks in Tajikistan, external as well.

The concern is that many countries would not be prepared for a return of polio.

Indian hope

Hope for the future stems from India. The country was once the epicentre of polio with more cases than any other country in the world.

In February 2012 it was removed from the list of endemic countries.

At the time prime minister Manmohan Singh said: "It is a matter of satisfaction that we have completed one year without any single new case of polio being reported from anywhere in the country.

"This gives us hope that we can finally eradicate polio not only from India but from the face of the entire mother earth. The success of our efforts shows that teamwork pays".

But the entire world would need to be polio-free for three years before the disease could truly be regarded as eradicated.

- Published24 May 2012

- Published25 September 2015

- Published1 October 2011

- Published27 February 2012

- Published20 February 2012