Centenarians vs newborns: Epigenetic differences reveal clues to ageing

- Published

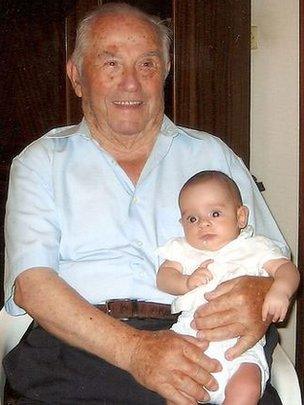

A newborn and a 103-year-old examined in the study

It's pretty easy to spot the difference between a newborn and a centenarian, but explaining how and why we age is far more challenging.

Why do we develop wrinkles and why do our muscles waste away? Why do our brains and immune systems become less effective with time?

In the search for clues to what is going on, researchers in Barcelona have looked in huge detail at the "epigenomes" of a newborn baby boy and 103-year old man. It's all part of the rapidly emerging and exciting field of epigenetics.

Epigenetics is all about changing the way our genes function by turning them off or making them more active.

Genes are the blueprint for building the human body. There's a copy of the whole blueprint in nearly every cell in the body, but clearly you don't need to use all of it all of the time. Bone cells will use different bits of the blueprint to nerve cells or light sensing cells in the eye.

Manel Esteller's team, at the Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute, has shown that this control over the blueprint decays over time.

Adding small chemicals, methyl groups, to specific points of DNA is one of the main ways of turning a gene off.

Prof Tim Spector of King's College London, explains what epigenetics are

The scientists compared the proportion of these sites which had an added methyl group in the white blood cells of a 103-year old man and newborn baby boy.

The findings, <link> <caption>reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences</caption> <url href="http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2012/06/05/1120658109" platform="highweb"/> </link> , showed the newborn had methyl groups turning genes off at more than 80% of all possible sites. This compared with 73% in the centenarian. That's a difference of nearly half a million sites between the two.

Another test on a 26-year-old showed 78% of sites were methylated.

Dr Manel Esteller says the implication of the study is that very tight control of genes at the beginning of our lives may be being lost as we age, with more genes being switched on over time.

He told the BBC that "epigenetics is playing a central role in ageing" and that epigenetic changes between newborns and centenarians were "affecting many, many genes".

This in turn could affect some of the physical traits associated with ageing.

Longer or healthier life?

It is possible to change a person's epigenome. Studies have already shown how a pregnant mother's diet can affect her <link> <caption>child's risk of obesity</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-13119545" platform="highweb"/> </link> epigenetically.

It begs the question: can we do anything about our epigenome in order to live a longer or healthier life?

"If it is something we can intervene from outside, maybe we can change the epigenome to change or slow ageing," Dr Esteller said.

Prof Tim Spector, the author of a book on epigenetics, Identically Different, said: "There are epigenetic drugs in development, four for cancer. In terms of lifestyle, we know that exercise can switch off the main obesity genes epigenetically.

"Apart from stem cells, this is the hot area of ageing at the moment, finding ways of encouraging our genes to remain healthy is going to be a top priority in the next few years."

Epigenetics is never going to be the whole story of ageing, but researchers certainly think changes in the way we use our DNA will make at least a few interesting chapters.

- Published2 November 2011

- Published26 January 2011

- Published14 March 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published10 September 2010