We must be sure three-person IVF is safe

- Published

- comments

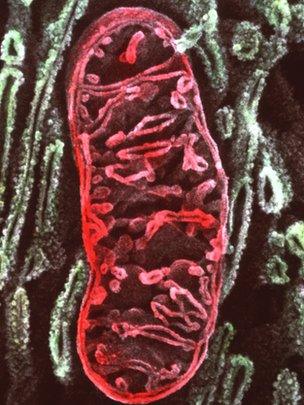

DNA from the mitochondrion is replaced in the new technique

Scientists have passed another hurdle in what could eventually lead to a new treatment to prevent some devastating genetic conditions from being passed from mother to child.

The US team, based in Oregon, created apparently healthy looking human embryos using genetic material from two women and a man.

The point of this research is to find a safe means of enabling women with seriously faulty mitochondrial DNA to have a healthy child. Mutations in mitochondria - the power packs outside the nucleus of each cell - can lead to potentially fatal diseases.

This would be done by replacing the faulty mitochondria with healthy DNA from a donor. This genetic change would be very small - almost all the genetic inheritance would still be passed from mother to child - but it would be permanent.

I have written already about the ethics of so-called three-person IVF, and a public consultation is being conducted by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, external.

You can read more about this latest research, published in Nature, here.

There are two very similar methods for overcoming mitochondrial disease - maternal spindle transfer and pronculear transfer. Both produce the same result: genetic material from two parents in an embryo containing healthy mitochondria from the donor.

Doctors need to know which would be the safest and most efficient technique to use in people.

The main difference between the techniques is when sperm become involved.

Spindle transfer

The US team used spindle transfer - chromosomes from the mother's egg are placed into a donor egg, which has been stripped of its own chromosomes. This is now fertilised with sperm to create an embryo.

The researchers showed it was possible to create healthy looking embryos, however, around half appeared abnormal.

The alternative, pronuclear transfer, method was pioneered two years ago at Newcastle University in the UK, using embryos deemed unsuitable for IVF.

Researchers fertilise the mother's egg and a donor egg first to create two embryos. The genetic information from mum and dad form a pair of "pronuclei" inside the embryo which will fuse to contain the complete genetic blueprint for a child. These pronuclei are transferred into the donor embryo, which has had its pronuclei removed.

Prof Mary Herbert, from Newcastle University, described the latest results as a "striking finding".

Although her team believe the pronuclear transfer method is more straightforward, and are currently trialling this method using healthy human embryos.

If this all sounds pretty technical, well it is, but there are is a graphic available which can show what's involved in each technique.

The question is which method will work best in humans? Neither the US nor Newcastle researchers has allowed any human embryos to be implanted - all were destroyed after just a few days when still smaller than a pinhead.

Animal trials may not be an entirely accurate guide. The US team say four rhesus macaques born in 2009 using spindle transfer were followed up for three years. They appeared entirely healthy.

But as yet no team has successfully done pronuclear transfer in monkeys, although experiments have been successful in mice using both techniques.

Some may suggest that further animal work with macaques is another necessary step before the technique is tried in humans. If so this could lead to several years delay as any monkeys born would need to be followed up for several years.

Although an expert committee in the UK concluded in 2011 there are no safety concerns that should prevent the technique from being used to help couples, it did recommend further research, including pronuclear transfer in monkeys.

Species difference

But this latest paper showed that spindle transfer was more successful in macaques than humans, highlighting a species difference that may raise questions over the usefulness, in this instance, of primate research.

Professor Robin Lovell-Badge of the Medical Research Council National Institute for Medical Research was co-chair of that 2011 scientific review.

"We had suggested that the other method (pronuclear transfer) be trialled in the macaque model just to make it parallel with what is known of this first method.

"To me this suggests its probably not absolutely necessary to do those experiments because it may well be that you get a different result simply because they are different species.and if this work reveals that there are differences, albeit subtle ones, between monkeys and humans, then we have to take very carefully that if you got a negative result in macaques it doesn't mean its going to be negative in humans or vice versa."

Prof Doug Turnbull, who is leading the team in Newcastle which is concentrating on the pronuclear transfer method, described the Nature paper as very encouraging and showed the idea of getting rid of mitochondrial disease was really possible. But, he cautioned, "we must also be sure of its safety".

Whenever a new technique is tried in humans for the first time there is always an element of risk. But given that the genetic changes made here will be permanent - passed on from generation to generation - it makes safety concerns even more important.

Ultimately it will be for the Health Secretary to approve and Parliament to vote on this issue - both the ethics and the science. Even if they do support it in principle a licence would then have to be issued by the HFEA.