New age of exploration in the hunt for extreme life

- Published

- comments

Lake Ellsworth is extremely remote

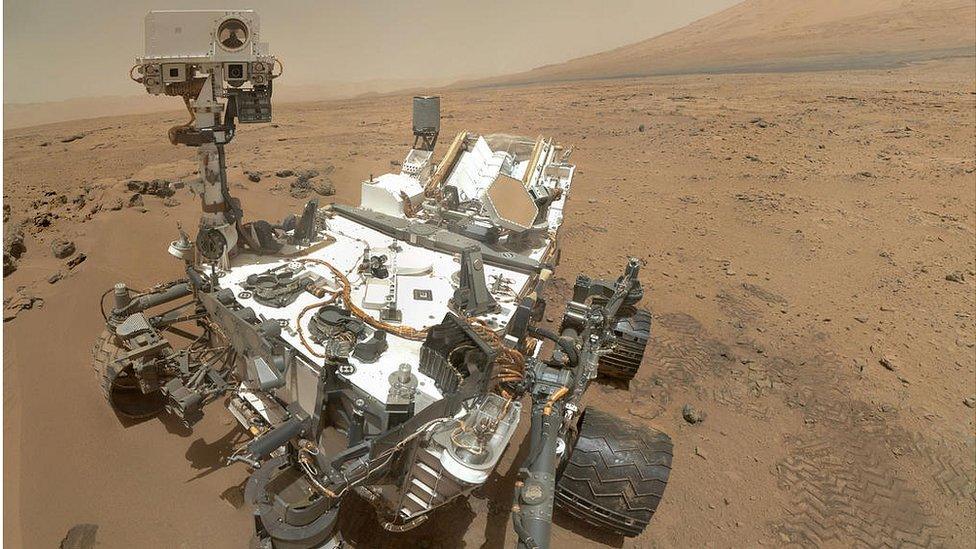

A two-billion-dollar robot scoops up pale-red samples on the surface of Mars to search for chemical clues in the powdery grains of the alien soil.

At the same time, British scientists brave a notoriously windswept plain in Antarctica to investigate an ancient lake lying hidden beneath the ice-sheet.

The two missions are exploring different planets but they share a similar aim: to understand the limits of life, one of the most fascinating questions in modern science.

In the arid dust of Gale Crater on Mars, Nasa's Curiosity rover is hunting for evidence about whether conditions in the now-dry valleys and stream-beds might ever have allowed anything to thrive.

A briefing on Monday, external did not yield the "history-making" results one scientist had promised, but showed how the instruments had found a mix of complex substances in a promising area.

Meanwhile, in the deathly white of Antarctica, the British researchers are also hoping to make history: they are about to drill through two miles of ice to reach the pitch-black waters of Lake Ellsworth , externalto see if organisms have survived in isolation for up to half a million years.

One expedition is being managed across the vastness of space, with scientists in California coping with a 20-minute delay to contact and remote-control their machine on Mars; the other requires hands-on skill and fortitude for the extreme challenge of operating in the penetrating cold.

Both projects are remote, involve journeys into the unknown and rely on a fundamental scientific principle in the search for life: the need for water.

Key connection

According to Professor Martin Siegert of Bristol University, the chief scientist of the Lake Ellsworth mission, water is the connection that binds the expeditions. I spoke to him before he flew South.

He said: "In both places we're looking to see if water is all you need for life or is there something else?

"We're both asking the same question: have we understood the physical limits of life?

"This really is a frontier of knowledge, a fundamental question of scientific curiosity."

Another similarity is the need for sterility. Any search for life or for clues about it relies on being sure that the mission itself has not contaminated the hunt.

In April last year, in a clean room at Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, I watched white-suited engineers gingerly assembling Curiosity. If any bacteria have survived the decontamination and the journey to Mars, they could cast doubt on whatever the rover might find.

The importance of this was made clear last night.

In a briefing, Nasa scientists announced that Curiosity had detected organic compounds - complex molecules containing carbon, without which no known life can develop.

Curiousity is analysing Martian soil samples

But they stressed that at this stage they could not be sure where those "organics" had come from - possibly from the spacecraft itself or from meteorites showering the Martian surface.

And every option has to be ruled out before the researchers will acknowledge that these vital chemical building-blocks might be "indigenous" or home grown and therefore open a door to the possibility of life on Mars.

This was not quite the "history-making" announcement that one of the scientists had suggested last week. But the search goes on and the rover has enough power to last two years with ancient streams and the slopes of a mountain to explore.

Basic life forms

Last January I saw another clean room in operation: this time at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton where the drilling and sampling components for Lake Ellsworth were being sterilised.

Again, the task was critically important. The search for microbial life beneath the ice would be wrecked if some organism was brought south in the equipment and confused any results about what might be found there.

Now the boilers, the massive hose, the winding system, the sampling probes and the full team are on site in a huddle of tents and shipping containers, this temporary settlement itself the only sign of life for hundreds of miles.

Next week, if all goes according to plan, a small mountain of snow will be melted, repeatedly sterilised and then injected in a high-pressure stream of near-boiling water to clear a bore-hole through the two miles of the ice-sheet.

Sometime in mid December, sampling devices will be lowered through the ice, lights picking out the descent for HD cameras, down into the black depths of the lake.

According to Prof Siegert, it would be "extraordinary" if the samples did not reveal signs of microbial life.

And the chances of finding it were boosted last week by research in another inhospitable polar corner.

A US team investigating Lake Vida in Antarctica's Dry Valleys reported finding life in the "syrupy brine" flowing through cracks in the frozen body of the lake - and this despite the conditions being pitch-black and six times saltier than seawater.

The researchers detected "abundant cellular life" which was "metabolically active", according to Alison Murray of the Desert Research Institute in Nevada. "This gives us a perspective," she said, "that life can exist and be sustained for thousands of years without any influence from the surface."

So if life can thrive in the dark, in isolation, in temperatures no warmer than -13C, where else could it be on Earth and beyond, on distant planets or moons for example?

Last week also brought news from Mercury that even this scorched rock, orbiting closest to the Sun, has billions of tonnes of water frozen in the shadows.

Endless fascination

There was even speculation about a dark material on the tiny planet that could conceivably contain the same organic molecules being hunted on Mars, the carbon-based building blocks that are essential to all life.

So what drives this endless fascination?

Prof Siegert is clear: "it's about fundamental exploration, our natural curiosity."

And he likens the interest in the current wave of expeditions to the public's excitement about science in the 19th century. Whipped up by Charles Darwin's new perspective on life and by visions of lost worlds conjured up by Jules Verne and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, that was an age of discovery.

"And in 100 years we'll look back at this time as an age of pure exploration when you can't predict what you will find.

"It's about opening up new frontiers."

- Published10 August 2012

- Published4 December 2012

- Published10 November 2012

- Published16 January 2012