First UK live liver donation to a stranger takes place

- Published

Daniel Broadhead decided to give a quarter of his liver to a stranger

A 21-year-old man has donated a quarter of his liver to a complete stranger in the first UK operation of its kind.

Daniel Broadhead, who underwent the four-hour operation in December, says he made the decision on purely altruistic grounds,

But this selfless act carries risks - there is a chance of one death in 200 procedures and the long-term effects on donors' health are not fully understood, experts say.

With more than 400 people currently waiting for a life-saving liver transplant in the UK, this type of donation needs serious consideration, doctors say.

A shortage of organs in the UK means one in five people who need a liver transplant will die before a suitable one is found.

Most people on the waiting list have to rely on organs that become available when someone on the organ donor register dies.

But a few now opt for living liver donation, a procedure more commonly carried out in countries where donations from people who have died are considered unacceptable on religious grounds.

So far every living liver donor in the UK has been a relative or friend of the recipient, undertaking this complex surgery in an attempt to save the lives of children and adults close to them.

'Physical risks'

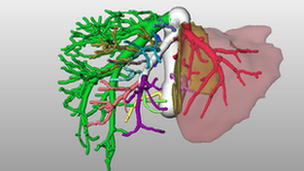

And despite having more than 500 different functions in the body, the liver has the ability to regenerate, making successful live donation possible.

But all living liver donors - whether they are related to the recipient or not - must carefully consider the two types of risks they face, says Dr Varuna Aluvihare, a transplant specialist at King's College Hospital, London.

There are the physical risks - first and foremost the risk of death - which is one in 200 cases.

This is considerably higher than the risk of death from more commonly carried out live kidney transplants - which is one death in every 1,700 cases.

And donors face a one in five chance of complications from surgery. Most of these can be relatively minor - for example treatable infections and pain after the operation.

.jpg)

Mr Broadhead has a 6in (15cm) scar from the operation which is healing well

But in rare cases donors' livers fail and they can end up needing transplants themselves, says Dr Aluvihare.

Raj Prasad, clinical director for surgery and transplantation at St James's University Hospital, Leeds, who undertook Mr Broadhead's operation, said in terms of the long-term risk to donors' health there is data spanning the first 12 years after donation which looks encouraging.

But possible future complications are less well known, he says.

Psychological assessment

There are also psychological risks - all living donors undergo rigorous psychological assessments too.

There have been some reports of donors suffering from psychiatric conditions including depression after donation, Dr Aluvihare says.

But altruistic donations, in which the donor has no connection to the recipient, need special consideration, says Mr Prasad.

He says that the donor needs to be checked that they have the capacity to make rational decisions and that the motivation for donation is clear.

Mr Broadhead under went two psychological assessments and the many medical tests all potential donors face.

"It was very clearly Daniel's wish to go ahead. He was in the right frame of mind and his state of health was right," said Mr Prasad.

His family were offered support too, but they found it hard to come to terms with his choice.

"They found it difficult to understand why I would put myself in harm's way for someone I didn't know," Mr Broadhead says.

"I tried to explain my reasons - that someone out there was going to die if not given a liver and while I am fit and healthy, I can do it. So why wouldn't I?"

Hearing about the risks involved did not deter him.

'Do it again'

"I tried to think of the risks from the point of view of the child who needed a liver so I kept the risks to myself to the back of my mind," he said.

The operation took place six weeks ago and has left Mr Broadhead with a 6in (15cm) scar.

Apart from a little pain when he goes for long walks, he is now recovering well and is even considering going back to work soon.

In fact, he says he would do it all over again if he could and would encourage other people to do the same.

Part of Mr Broadhead's liver was removed in a four-hour operation

But whether more altruistic donations should take place is open for debate.

Both Mr Prasad and Dr Aluvihare agree there is a place for encouraging more living donations from relatives.

And both doctors admire Mr Broadhead for taking on such risks to save a young person.

"But I personally have some reservations about altruistic donations. I believe if we did everything we can to improve the supply of donations after death we wouldn't have a need for this type of donation," Dr Aluvihare says.

He suspects the psychological risk may be greater for altruistic donors than for people who donate to their relatives and friends.

And the physical risks cannot be forgotten.

"If we do 400 of these then statistically at least one altruistic donor will die and that immediately changes our perspective on this."

- Published22 January 2013