Analysis: A cure for HIV?

- Published

A baby girl has been "functionally cured" of HIV in the US. The difference it will make to her life could be huge - avoiding a lifetime of medication, social stigma and worries about whether to tell friends and family.

But beyond the personal story, there is a huge question - does this bring us any closer to an HIV cure?

There are very special circumstances involved in the US case. Doctors were able to hit the virus hard and early. This is not possible in adults, who will acquire HIV months if not years before they find out.

Even in the UK, where at-risk groups are offered free regular testing - one in four people with HIV is unaware they have the virus. By the time they find out, it will be fully established - hiding away in reservoirs in the immune system that no therapy around can touch.

It is also unclear how a newborn's immune system, babies still get much of their protection from their mother through breast milk, may affect treatment.

One thing is certain - this approach is not going to provide a cure for the vast majority of people with HIV.

So what about about somebody who has been living with HIV for a decade? Any hope of a cure for them?

The first thing to note is that HIV is not the killer it used to be.

It first emerged in Africa in the early 20th Century, external and became a global health problem by the 1980s. In the early days, there was no treatment, never mind talk of a cure.

The virus claimed the lives of more than 25 million people, external in the past three decades, according to the World Health Organization.

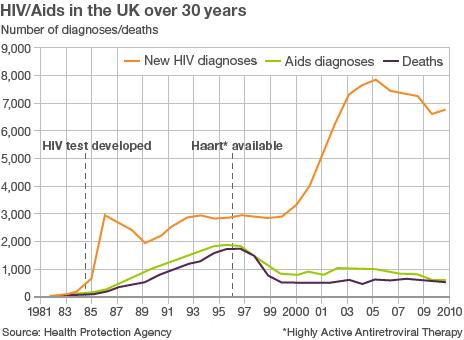

Then, good antiretroviral therapies emerged in the mid-1990s and the impact it had on the number of deaths was dramatic.

People infected with HIV should have a near normal lifespan if they have access to treatment. Of course this is a big "if". Nearly 70% of people living with HIV are in sub-Saharan Africa, external, where access to drugs is relatively poor.

'Weak spot'

The hunt is on for a cure.

"We had always assumed that it was impossible, but we've started to discover things we didn't know before and it's opening up a chink in the armour," Dr John Frater, from the University of Oxford, told the BBC.

"A cure is something we can no longer write off as impossible."

After HIV first infects the patient, the virus spreads rapidly, infecting cells all over the body.

Then, the virus hides inside DNA where it is untouchable.

But there are now experimental cancer drugs that might be able to flush the virus out and make it vulnerable.

Dr Frater said: "It turns on a virus inside a cell and it becomes visible to the immune system and we can target it with a vaccine."

However, this approach requires drugs to make the virus active and a vaccine to train the immune system to finish it off - this is not just round the corner.

"We are a long, long way away, in truth," said Dr Frater.

There is another route being considered - involving a rare mutation that leaves people resistant to HIV infection.

In 2007, Timothy Ray Brown became the first patient believed to have recovered from HIV. His immune system was destroyed as part of leukaemia treatment. It was then restored with a stem-cell transplant from a patient with the mutation.

A little bit of genetic engineering may also help to modify a patient's own immune system so that it has the protective mutation. Once again this is a distant prospect.

'Uncertain'

Chairman of the UK-wide Aids vaccine programme Prof Jonathan Weber, from Imperial College, said: "For established infection we have some ideas, but it is all in the realms of experimental medicine.

"There is no consensus and no clear way forward."

He added a cure would be very cost-effective, as giving people drugs every day of their life was expensive.

Prof Jane Anderson, consultant at Homerton hospital in London, expressed caution about expecting a cure after the case in the US.

"This is a very exciting moment, but it is not the answer in today's world.

"I'm worried that we so desperately want a cure that we forget the cost-effective stuff that does make a difference."

Nearly every case of mother-to-child transmission can be prevented by drugs, caesarean section and not breastfeeding. And in adults, most cases are as a result of unsafe sex.

HIV really is an infection where prevention is much easier than cure.

- Published4 March 2013

- Published30 November 2011

- Published12 February 2012

- Published28 October 2012

- Published12 May 2011

- Published17 January 2013