Rapid diagnostic test promises end to leprosy torment

- Published

Celio Marques waited four years for a diagnosis

Leprosy is one of the classic scourges of ancient times. But it's far from being consigned to history - with over 200,000 new cases reported each year.

Although it's easily treated with antibiotics, people living in remote communities often go undiagnosed and are left with permanent damage. Now a new, cheap test - "the cost of one ice-cream" - could help doctors to stop the disease in its tracks.

Celio Marques was 16 years old when he first noticed pain and weakness in his hands and feet.

He was showing the early signs of leprosy but was treated for rheumatism for three years, allowing the disease to spread.

When the correct diagnosis finally came at the age of 20, Marques thought his life was over.

"Back then, the doctor told me - you have a disease that kills, that makes your limbs fall off. You have to go away. I was desperate and tried to kill myself. But then I learned what the disease really is and how to treat it."

Thirty years have passed and Mr Marques, who lives in Rio de Janeiro, is fully cured of the disease. But he's had to learn to live with the damage caused by the late diagnosis.

His fingers are permanently bent inwards and he has reduced movement in his hands and feet. He lost his eyebrows and his ears are swollen. Early diagnosis would have brought a very different outcome.

A modern day problem

After India, Brazil has the second highest number of leprosy infections in the world, accounting for 90% of cases in Latin America.

Dr Francisco Reis Viana, who has been treating leprosy at the Curupaiti Hospital in Rio for the past 30 years, says that finding all of those infected is still a huge challenge.

"The situation in Brazil is grave. The country has 30,000 new cases each year and it's difficult to contain because the disease is spread out and it's hard to diagnose and treat everyone," he told BBC reporter Julia Carneiro.

Leprosy attacks the nervous system which can cause damage to limbs.

"Because of the long incubation period, people can transmit the disease to others for years before knowing they have it."

As most of the infections happen in poor and often remote areas, the task of spotting and treating the disease early becomes even harder.

But now there's new hope for diagnosing leprosy before it infects others and causes physical damage.

A laboratory in Rio, OrangeLife, has just introduced a test - similar to a pregnancy test - that uses a drop of blood to diagnose leprosy in around 10 minutes.

Marco Collovati, president of OrangeLife, says each test will cost less than a dollar - "just the cost of one ice-cream":

"The rapid test allows us to detect the disease early, before the patient has lesions to the nerves and deformations," he says.

"This is a real revolution after more than 3,000 years of a disease which has caused so much stigma, suffering and prejudice."

New test looks promising

Collovati says the rapid test is easy to use in the field and has "huge potential" to reach remote areas where getting a diagnosis is currently very difficult.

The new test takes less than ten minutes and will cost less than one dollar

"It can be taken anywhere. It doesn't need to be refrigerated and can be used by any health agent with very basic training. All it takes a prick to the finger," he says.

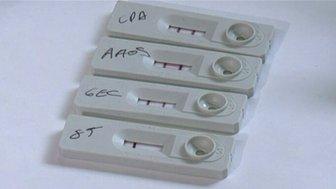

The test - half the size of a credit card - takes one drop of blood and a reactive strip inside detects antibodies produced against the infection. Just like a pregnancy test, it is two lines for a positive result and one line if it is negative.

With an accuracy of approximately 90%, it will detect most cases of early-stage leprosy. For the remaining 10%, says Mr Collovati, patients produce too few antibodies to be detected.

The Brazilian government is going to test the product in two of the worst affected parts of the country later this year, before adopting it more widely.

The new test looks a bit like a pregnancy test, with two lines indicating a positive result

Celio Marques, whose life was changed so radically by leprosy, is hopeful that the new test will help others find treatment without the suffering and damage he has had to endure.

Five years after his diagnosis he discovered he had been fired from his job in construction - regarded as an invalid.

He then met people suffering from similar problems at an organisation in Rio which helps people with leprosy. Today, he does voluntary work there, helping other people understand what the disease is and how to treat it.

"Treating the disease today is easy. The problem is when it causes damage. If I could have known about it earlier, I wouldn't have these marks," he says.

Leprosy is a disease that has terrified people since biblical times - the hope now is to make it a thing of the past.