Brain scan study to understand workings of teenage mind

- Published

- comments

Professor Ed Bullmore explains how the study will work and what his team is looking for

Researchers in Cambridge have begun a study to understand the teenage brain.

They have told BBC News that they will scan 300 people aged between 14 and 24 to see how their brains change as they grow older.

The £5m study, external aims to identify changes to the brain's wiring that controls impulsive and emotional behaviour as young people mature.

The investigation should also shed light on the emergence of mental disorders in young adults.

Psychological studies have documented that people act less impulsively as they become older. The purpose of the study at Cambridge University is to see whether those changes are associated with the structure of the brain.

What is going on in his brain? Harry Enfield's Kevin the Teenager: a painfully accurate parody of teenage behaviour.

Ed Bullmore who is a professor of psychiatry at Cambridge University believes that changes to the brain's wiring enable the teenage brain to cope with and then eventually control the emotions that initially overwhelm the young mind.

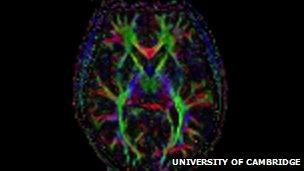

"MRI scans will give us very good pictures of how the anatomy of the brain changes over the course of development," he told BBC News. "We are particularly interested in how the tissue at the centre of the brain, known as white matter, might change over the course of development."

White matter can be thought of as bundles of wires in the middle of the brain that connect to various different cells and on the surface of the brain, known as grey matter.

Prof Bullmore believes that scans of the 14 to 24-year-olds his team is studying will show gradual changes in the white matter as the brain begins to regulate powerful signals generated by the body's hormones and the subjects gain control of their impulsive behaviour.

The subjects will also undergo tests that assess their propensity toward impulsive and risk-taking behaviour. The expectation is that the emergence of more sensible behaviour will correlate with changes in the wiring of the brain's white matter. According to Dr Becky Inkster, also from Cambridge University, this comparison will enable researchers to directly associate the shape of the wiring with behaviour patterns that all adults have gone through.

"Arguably we've all been there and it's a very awkward and complex and confusing time of life. So to be able to express oneself is quite difficult. So by the use of imaging and other tools we can really tap into these features of the adolescent brain and understand how they develop over time as they become a young adult."

This type of scanning has only been possible relatively recently and is being used in a US-led study, called the Human Connectome Project, to understand how the adult brain works. This is the first detailed scanning study to learn about the workings of the teenage brain.

Among the first to undergo a scan is 16-year-old Samantha whom I met with her mother Kim. She told me that she was all too aware of her daughter's mood changes.

Moody

"If something has upset her at school she can be quite moody when she comes home sometimes but it doesn't last that long."

Samantha laughed when I asked her if she recognised this.

"When I was about 15 or 16, that's when I noticed the change the biggest. Instead of being happy all the time - I would be quite moody, angry, and I would have arguments. I just changed completely."

And then I asked her whether she felt she was changing back, perhaps becoming a little more in control?

"Sometimes, and then sometimes I think no," she laughed.

Sam did however say that she felt relieved that her occasional moody bursts were down to her brain wiring.

Kim with her daughter Samantha, who, she says, has her moments

"I felt really guilty when I started being really moody- but learning it is just what happens- I don't feel so bad anymore".

Prof Bullmore expects to see changes in the brain's wiring that gradually bring impulsive behaviour under control.

"I think we are going to find that the decision-making process in the younger teenagers we expect to be more driven by short-term considerations, immediate emotional states, immediate past history of what was rewarding," he said.

Accelerate maturation

The brightly coloured areas show the connections between areas of Samantha's brain. It is this wiring diagram that is expected to change over the years.

The question many parents of teenagers will be asking is whether the rewiring can be hurried up?

And they would be pleased to hear that Prof Bullmore thinks it can.

"I think that kind of application of the work we are doing is not inconceivable in the future. If we can understand both mentally and physically what's changing in the brain then we are in a better position to design interventions that could support or accelerate maturational change in the way people think," he said.

"You could imagine that it might be possible to develop computerised games or other training programmes that could help adolescents develop advance cognitive skills faster than they otherwise would."

This raises the interesting notion of parents locking teenagers in their bedrooms, forcing them to play computer games for hours on end.

The researchers also hope to learn from this Wellcome Trust-funded study, how mental disorders might develop. It is in the late teens and in early adulthood that there is a high risk of developing psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. This is especially the case for girls where there is a high risk of mood disorders and depression.

A number of other issues are likely to arise for the first time at this stage including drug and alcohol misuse and dependency.

Mental illness

Many psychiatric disorders that are thought of as problems of adulthood actually often arise for the first time in adolescence and by examining the scans of his volunteers Prof Bullmore hopes to learn whether at their root these conditions are abnormalities in brain development.

"We don't really have a good way of explaining (mental illness) to people because to be honest we don't have a particularly good insight into the details ourselves at the moment," he said.

"We will do a better job of explaining to ourselves and to patients how, for example, schizophrenia emerges in a 19 or 20-year-old for the first time, how we can relate that a little bit more directly to changes in brain development that may have been going subtly wrong for many years previously," he said.

Better understanding will help in the development of better treatments - but the goal in the medium term is to be able to identify potential problems early on and carry out an accurate prognosis.

Predicting psychosis

Parents, for example, often see that their son or daughter is developing depression or a psychosis. What is important to them is the long-term outcome: are they going to be able to recover, are they going to be able to go to university or does this indicate that they are on a different trajectory of a long-standing pattern of illness?

"By building understanding I think we can get away from the idea that mental illness in young people is primarily a moral problem or a random disaster and try and move understanding more toward a rational direction," said Prof Bullmore. "Can we think about psychosis, depression and other disorders that arise in adolescence as departures from the normal process of developmental change in the brain?"

Follow Pallab on Twitter @bbcpallab, external

- Published17 February 2013

- Published5 March 2013