Optician's clinic that fits a pocket

- Published

Mirriam Waithara had cataracts removed and can now see again

Cataracts cloud Mirriam Waithara's world and leave her almost blind.

She lives in a poor and remote part of Kenya where there are no opticians to pick up the problem and she is far from the only one.

The World Health Organization says 285 million people are blind or visually impaired.

The reason is often simple and easy to treat. A pair of glasses or cataract surgery can transform someone's eyesight.

It is thought that four out of every five cases can be prevented or cured.

Even in the poorest parts of the world there are often eye doctors in the major towns and cities.

However, says Dr Andrew Bastawrous of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, finding patients is often the problem.

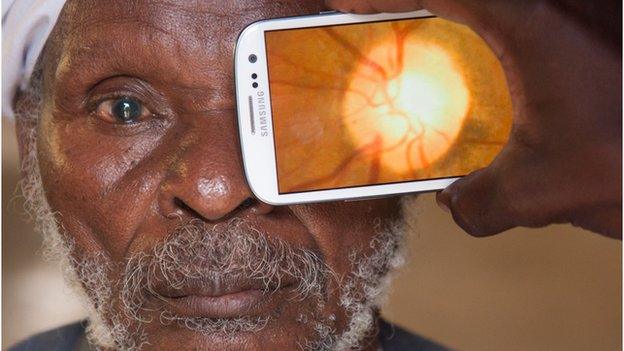

The mobile app in action: Scanning the back of the eye

"Patients who need it most will never be able to reach hospital because they're the ones beyond the end of the road, they don't have income to find transport so we needed a way to find them," he told the BBC.

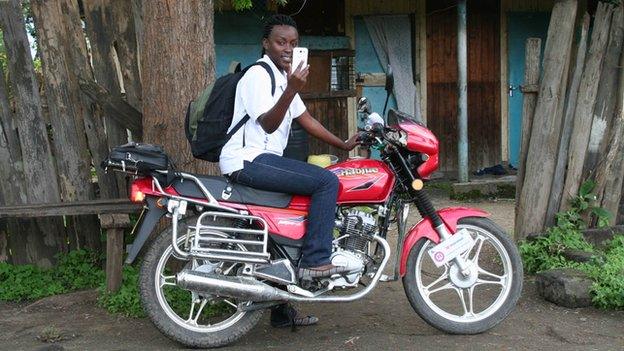

But he thinks he has come up with a solution that is mobile and can be used with very little training.

He is trialling a smartphone app called Peek, external (Portable Eye Examination Kit) on 5,000 people in Kenya.

It uses the camera to scan the lens of the eye for cataracts.

A shrinking letter which appears on screen is used as a basic vision test.

And it can uses the camera's flash light to illuminate the back of the eye, the retina, to check for disease.

A patient's records are stored on the phone, their exact location is recorded using GPS and the results can be emailed to doctors.

The phone can be used to look at the retina at the back of the eye and check the health of the optic nerve

It can also scan the eye lens for cataracts

Letters on the phone display function as a basic vision test

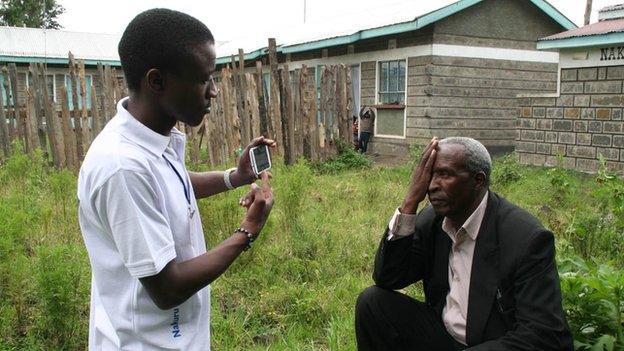

The idea is the phone is mobile and can be used with minimal training.

If problems are identified then patients can be taken for treatment.

The phone is relatively cheap, costing around £300 rather than using bulky eye examination equipment costing in excess of £100,000.

But does it give the same diagnosis?

The images taken on the phone during the tests in Nakuru, Kenya, are being sent back to Moorfield's Eye Hospital in London.

The pictures are being compared with ones taken with conventional eye examination gear, which has been transported around the region in the back of a van.

The study is not complete, but the research team say the early results are promising and that 1,000 people have received some form of treatment so far.

They include Mirriam Waithara. She had an operation to remove her cataracts and can now see again.

"What we hope is that it will provide eye care for those who are the poorest of the poor," Dr Bastawrous said.

"A lot of the hospitals are able to provide cataract surgery which is the most common cause of blindness, but actually getting the patient to the hospitals is the problem.

"What we can do using this is the technicians can go to the patients to their homes, examine them at their front doors and diagnose them there and then."

The idea is already attracting praise even at an early stage.

Peter Ackland, from the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, said: "I think the Peek tool is potentially a huge game changer.

"If you're a breadwinner and you can't see and you can't work then the whole family is in crisis.

"At the moment we simply don't have the trained eye health staff to bring eye care services to the poorest communities. This tool will enable us to do that with relatively untrained people."

The greatest need is in poor countries where around 90% of the world's blind and visually impaired people live.

Mr Ackland believes Africa and northern India will be the places most likely to benefit as ophthalmologists and optomotetrists there are operating at around 30-40% of their capacity.