UK government backs three-person IVF

- Published

Opponents fear that other forms of genetic modifications could follow

The UK looks set to become the first country to allow the creation of babies using DNA from three people, after the government backed the IVF technique.

It will produce draft regulations later this year and the procedure could be offered within two years.

Experts say three-person IVF could eliminate debilitating and potentially fatal mitochondrial diseases that are passed on from mother to child.

Opponents say it is unethical and could set the UK on a "slippery slope".

They also argue that affected couples could adopt or use egg donors instead.

Mitochondria are the tiny, biological "power stations" that give the body energy. They are passed from a mother, through the egg, to her child.

Defective mitochondria affect one in every 6,500 babies. This can leave them starved of energy, resulting in muscle weakness, blindness, heart failure and death in the most extreme cases.

Research suggests that using mitochondria from a donor egg can prevent the diseases.

It is envisaged that up to 10 couples a year would benefit from the treatment.

However, it would result in babies having DNA from two parents and a tiny amount from a third donor as the mitochondria themselves have their own DNA.

'Clearly sensitive'

Earlier this year, a public consultation by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) concluded there was "general support" for the idea and that there was no evidence that the advanced form of IVF was unsafe.

The chief medical officer for England, Prof Dame Sally Davies, said: "Scientists have developed ground-breaking new procedures which could stop these disease being passed on, bringing hope to many families seeking to prevent their future children inheriting them.

"It's only right that we look to introduce this life-saving treatment as soon as we can."

She said there were "clearly some sensitive issues here" but said she was "personally very comfortable" with altering mitochondria.

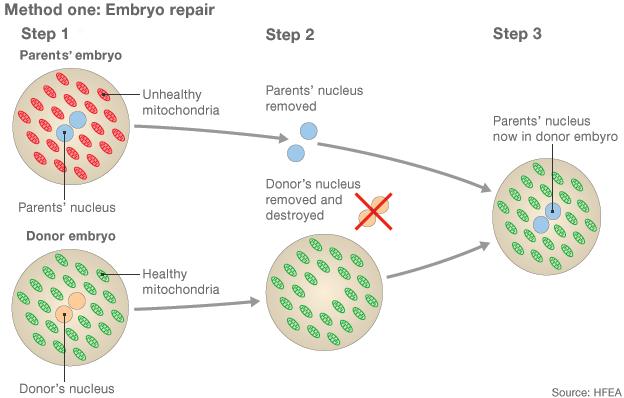

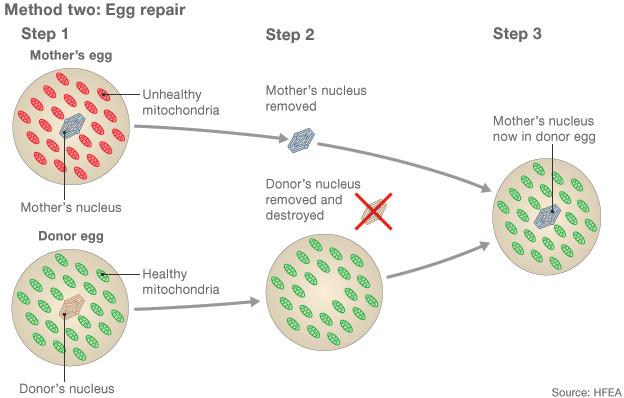

Scientists have devised two techniques that allow them to take the genetic information from the mother and place it into the egg of a donor with healthy mitochondria.

1) Two eggs are fertilised with sperm, creating an embryo from the intended parents and another from the donors 2) The pronuclei, which contain genetic information, are removed from both embryos but only the parents' is kept 3) A healthy embryo is created by adding the parents' pronuclei to the donor embryo, which is finally implanted into the womb

1) Eggs from a mother with damaged mitochondria and a donor with healthy mitochondria are collected 2) The majority of the genetic material is removed from both eggs 3) The mother's genetic material is inserted into the donor egg, which can be fertilised by sperm.

The result is a baby with genetic information from three people.

They would have more than 20,000 genes from their parents and 37 mitochondrial genes from a donor.

It is a change that would have ramifications through the generations as scientists would be altering human genetic inheritance.

Dr David King says the move crosses "a crucial ethical line"

Objections to the procedure have been raised ever since it was first mooted.

Dr David King, the director of Human Genetics Alert, said: "These techniques are unnecessary and unsafe and were in fact rejected by the majority of consultation responses.

'Designer baby'

"It is a disaster that the decision to cross the line that will eventually lead to a eugenic designer baby market should be taken on the basis of an utterly biased and inadequate consultation."

One of the main concerns raised in the HFEA's public consultation was of a "slippery slope" which could lead to other forms of genetic modification.

Draft regulations will be produced this year with a final version expected to be debated and voted on in Parliament during 2014.

Newcastle University is pioneering one of the techniques that could be used for three-person IVF.

Prof Doug Turnbull, the director of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Mitochondrial Research at the university, said he was "delighted".

Mother: I can't just go and get pregnant

He said: "This is excellent news for families with mitochondrial disease.

"This will give women who carry these diseased genes more reproductive choice and the opportunity to have children free of mitochondrial disease. I am very grateful to all those who have supported this work."

The fine details of the regulations are still uncertain, yet it is expected to be for only the most severe cases.

It is also likely that children would have no right to know who the egg donor was and that any children resulting from the procedure would be monitored closely for the rest of their lives.

Sir John Tooke, the president of the Academy of Medical Sciences, said: "Introducing regulations now will ensure that there is no avoidable delay in these treatments reaching affected families once there is sufficient evidence of safety and efficacy.

"It is also a positive step towards ensuring the UK remains at the forefront of cutting-edge research in this area."

- Published28 June 2013

- Published20 September 2012

- Published28 June 2013

- Published20 March 2013

- Published12 June 2012