A bold step for science and society

- Published

- comments

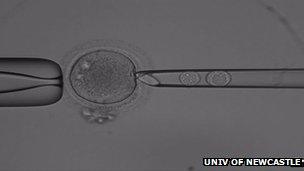

Human pro-nuclei being transferred to donor embryo at Newcastle

The decision of the government to support a ground-breaking technique for preventing serious genetic disease is a bold step for science and society.

Many researchers thought ministers would sit on this controversial issue. Instead, the chief medical officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies, has announced that draft regulations will be published within months.

She predicts that couples affected by mitochondrial disease could benefit from the treatment within two years, enabling them to have healthy children.

So why is this such a significant moment?

Firstly the UK will become the first country to allow the technique, aimed at preventing a range of potentially deadly genetic disorders.

This will underline Britain's pioneering role in genetics and IVF stretching back to both the discovery of the structure of DNA in 1953 and the birth of Louise Brown, the world's first test tube baby, in 1978.

Secondly, the technique itself will result in babies with DNA from three people - two women and a man - and this genetic alteration will be passed down the generations.

Once babies have been born using this technique, there will be no going back. A permanent and novel genetic change to members of the human race will have been made.

That might sound pretty worrying, and talk of three people's DNA mixed together seems a bit ghoulish at first glance. So is this science overstepping the mark?

A public consultation conducted by the fertility regulator, the HFEA, found there was broad support for the technique, once the details had been explained.

So let's look briefly at the science.

The science of mitochondrial repair

Mitochondria are the energy factories of cells. They contain a tiny bit of DNA and just 37 genes, sitting outside the nucleus which has more than 20,000 genes - including all the crucial genetic material from both parents.

Mitochondrial disorders are always passed down the maternal line in the egg, so the technique being pioneered by Prof Doug Turnbull and his team at Newcastle University involves using healthy donor eggs.

Put briefly, conventional IVF is performed and then, after fertilisation, the pro-nuclei of the father and mother - you can see them clearly as the two round balls inside the glass tube in the picture above - are sucked out of the developing embryo.

This leaves behind the faulty mitochondria. The parents' genetic material is then injected into a healthy donor egg which has had its pro-nuclei removed but still has healthy mitochondria.

The scientists believe the resulting embryo should develop normally. It means all the crucial parental genes will be retained, plus a tiny amount of DNA from the female donor.

Double helix

So how much DNA from the second woman is there? There is 1.05 metres of DNA in the nucleus and 0.0054 mm of DNA in our mitochondria.

Let's put that another way. If you imagine the DNA in your nucleus - remember this is all the important stuff which makes us what we are - and stretched it from Trafalgar Square to Prof Turnbull's laboratory in Newcastle, you'd have a double helix of 282 miles.

Now if you laid all the DNA from the mitochondria alongside it, it would stretch from Trafalgar Square, barely round the corner to the National Portrait Gallery - just a couple of hundred yards. That perhaps gives you an idea of just how little DNA is involved.

The scientists in Newcastle say their technique is akin to changing the battery of a laptop computer. The hard-drive - containing all the important information - is the parental DNA in the nucleus which remains unchanged. The battery is simply the power source.

Animal research and a number of scientific reviews suggest the technique is safe. But the Newcastle team reckon they have another year or more research to do before they will be completely satisfied.

One limiting factor for the researchers is the shortage of healthy donor eggs. They need women in the Newcastle area who are prepared to altruistically donate their eggs.

Another team in Oregon is using a similar technique and is discussing future research with the American regulators.

The next step here will be the publication of draft regulations.

There will be a debate and a free vote in parliament. A final scientific review of safety will be made and then assuming all hurdles have been passed, it will be open to the Newcastle team to apply for a licence from the HFEA. Each case, each couple being treated, will require a separate licence.

But before then, further public debate is being actively encouraged - this is an occasion where science, ethics and regulation seem to be proceeding at the same pace.

There will be some who find this disturbing - tampering with nature. But for the families affected by mitochondrial disease it is a chance to have a healthy child, and to ensure that future generations are healthy too.

We may look back on this development as one of the key moments in science and ethics of modern times.

- Published28 June 2013

- Published20 September 2012