Mers coronavirus: Dromedary camels could be source

- Published

Researchers say further investigation is needed

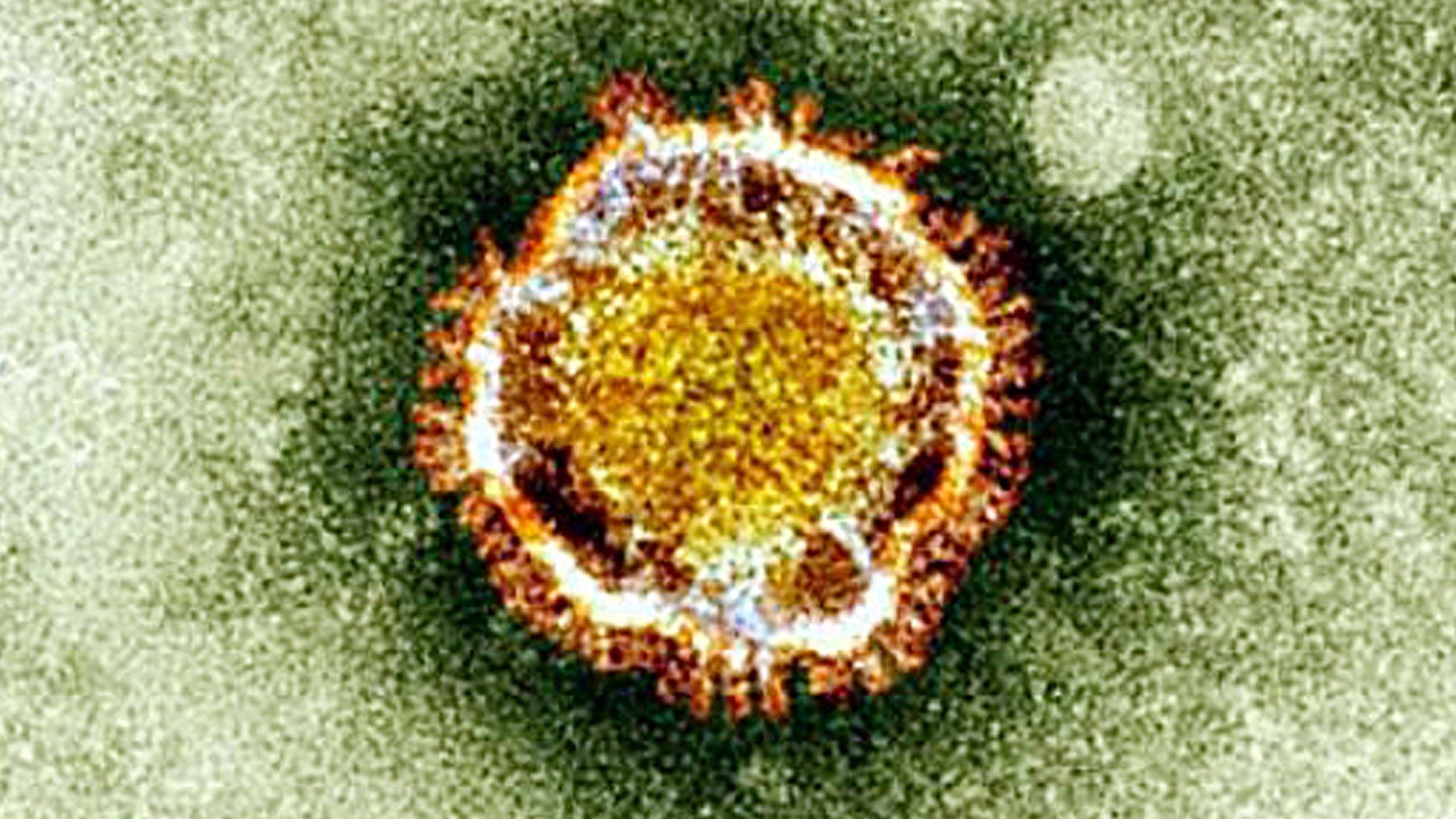

Dromedary camels could be responsible for passing to humans the deadly Mers coronavirus that emerged last year, research suggests.

Tests have shown the Mers (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) virus, or one that is very closely related, has been circulating in the animals, offering a potential route for the spread.

The study is published in the journal Lancet Infectious Diseases, external.

But the scientists say more research is needed to confirm the findings.

The Mers coronavirus first emerged in the Middle East last year. So far, there have been 94 confirmed cases and 46 deaths.

While there has been evidence of the virus spreading between humans, most case are thought to have been caused by contact with an animal. But until now, scientists have struggled to work out which one.

'Smoking gun'

To investigate, an international team looked at blood samples taken from livestock animals, including camels, sheep, goats and cows, from a number of different countries.

They tested them for antibodies - the proteins produced to fight infections - which can remain in the blood long after a virus has gone.

Professor Marion Koopmans, from the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment and Erasmus University in The Netherlands, said: "We did find antibodies that we think are specific for the Mers coronavirus or a virus that looks very similar to the Mers coronavirus in dromedary camels."

The team found low levels of antibodies in 15 out of 105 camels from the Canary Islands and high levels in each of the 50 camels tested in Oman, suggesting the virus was circulating more recently.

"Antibodies point to exposure at some time in the life of those animals," Prof Koopmans explained.

No human cases of the Mers virus have been reported in Oman or the Canary Islands, and the researchers say they now need to test more widely to see if the infection is present elsewhere.

This would include taking samples from camels in Saudi Arabia, the country where the virus is the most prevalent.

'Priority search'

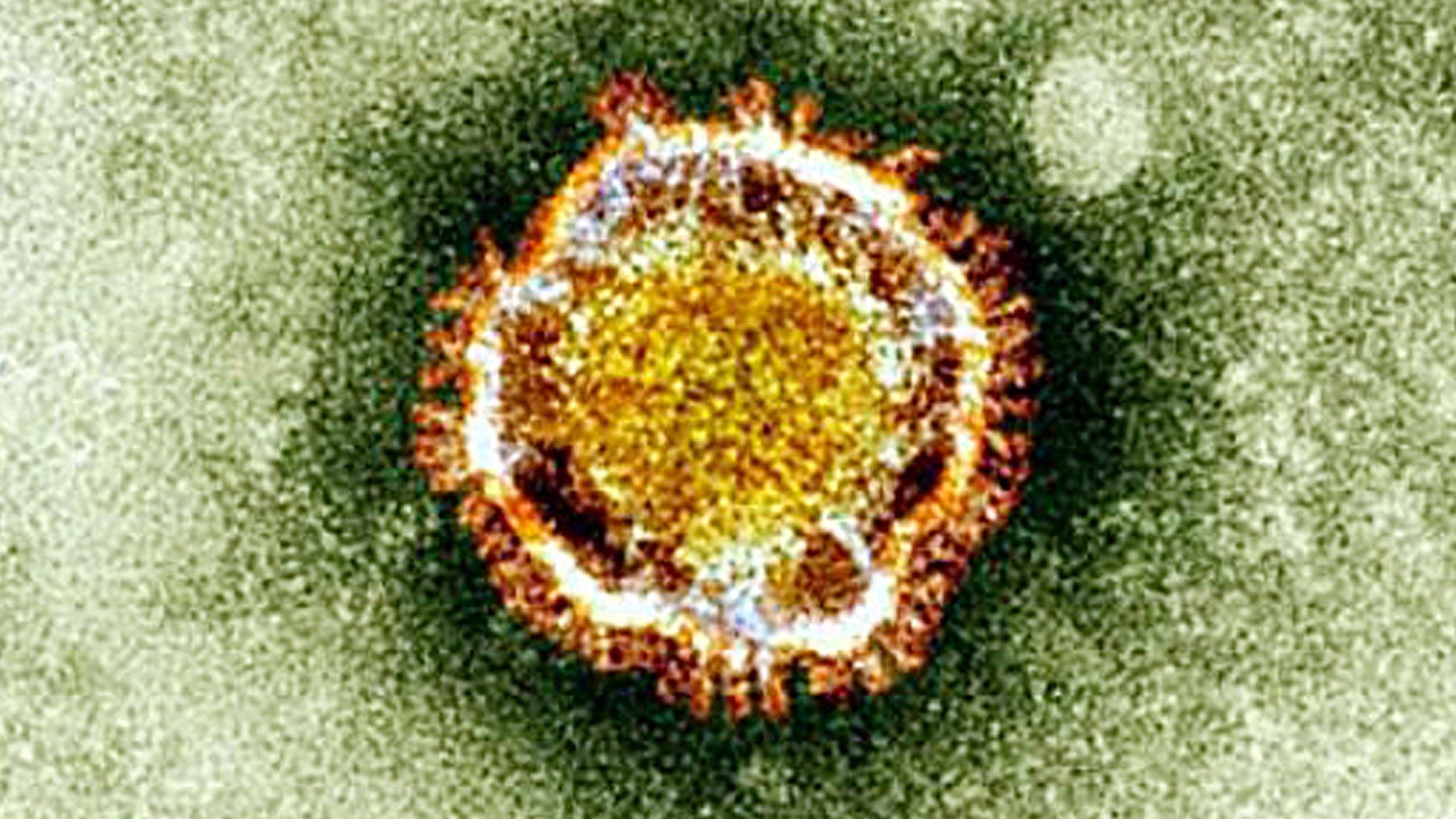

Prof Koopmans said: "It is a smoking gun, but it is not definitive proof."

Commenting on the research, Professor Paul Kellam from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge and University College London, said the research was helping to narrow down the hunt for the source of the virus.

But he told BBC News: "The definitive proof would be to isolate the virus from an infected animal or to be able to sequence and characterise the genome from an infected animal."

Health officials say confirming where the virus comes from is important, but then understanding how humans get infected is a priority.

Gregory Hartl, from the World Health Organization, said: "Only if we know what actions and interactions by humans lead to infection, can we work to prevent these infections."

Data suggests that it is not yet infectious enough to pose a global threat and is still at a stage were its spread could be halted.

- Published2 July 2015

- Published5 July 2013

- Published13 May 2013

- Published23 June 2013

- Published20 November 2012

- Published28 May 2013

- Published19 February 2013

- Published13 February 2013