Phone app offers 'verbal autopsies' to improve death records

- Published

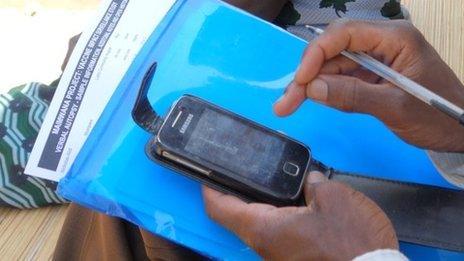

Autopsy mobile phone app

Two thirds of deaths worldwide go completely unrecorded, making it impossible to know if public health money is being spent in the right places. But could a mobile phone app be the answer?

Birth and death are perhaps the most significant moments of any human life - worth writing down for posterity.

But in many countries around the world, the systems set up to collect vital data about citizens have such low coverage that many deaths slip through the net.

Not knowing who has died, and what they have died of, makes it impossible to build an accurate picture of a nation's health.

Now technology - in the form of a specialist mobile phone app - could make all the difference.

Using a technique known as "verbal autopsy", field workers visit relatives to ask them about the circumstances of a family death.

By collecting the information digitally from currently hard-to-reach places, it has the potential to revolutionise our understanding of global health.

Mobile phone autopsies

In Malawi, any death that occurs outside a medical facility is not recorded.

Dr Carina King, a fellow at University College London, is overseeing the implementation of the mobile phone autopsies in the Malawian district of Mchinji.

"We found everyone surprisingly open, and I think they find the phone quite an interesting thing when we go for interviews," she told the BBC.

Verbal autopsies have been in use for about 20 years but the information was traditionally recorded on a paper questionnaire.

These often lengthy documents were supposed to be analysed by two doctors, who would use the answers to deduce the likely cause of death.

However the sheer scale of the task was often too great, meaning that many of the questionnaires ending up languishing in dusty rooms, completely unread.

"The mobile phone has been very good and means we don't have lots of paper forms," says Dr King.

"We have very quick access to the data and we can analyse it quickly to get the causes of death."

The phone software, known as MIVA, presents a series of questions that a trained field worker uses to find out information from the family.

Each question has a range of possible answers and the software intelligently skips to the next relevant question depending on the response.

Most important of all is that it is designed to quickly compute the most likely cause of death.

The result is stored in the phone and can be sent to a central database either by text message or internet upload.

'Cheap and robust' technology

Dr Jon Bird of City University, London, who was part of the team involved in creating the software, says mobile phones provide a particularly convenient way of collecting data.

"Mobile phones are probably one the most widespread technologies in the world. They're cheap, they're robust and everyone knows how to use one," he told the BBC.

"The everyday nature of mobile phones also makes them really valuable because the people that are being interviewed don't find them intrusive."

In Malawi, mobile phone autopsies are currently being used to record the cause of death in children.

The project is called MaiMwana, meaning mother and child in the local Chichewa language, and it focuses on children who died before their fifth birthday.

The under-five mortality rate in Malawi is 71 per 1,000 live births according to 2012 figures from the World Bank - compared to just five per 1,000 live births in the UK.

Verbal interviews with relatives of the deceased are recorded onto the app

Lazaro Cypriano lives in the village of Mzangawa in Mchinji district, central Malawi with his wife Magdalena and their toddler.

The couple lost their first two children.

Their second child died about a year ago, after a series of hospital visits due to fever. It is this death that will be the subject of the verbal autopsy.

'Highly sensitive'

Outside urban areas, one of the main problems for collecting data is finding out when a death has occurred.

To get around this, field reporters from the local community take on the responsibility of alerting the MaiMwana team of people who have died in their area.

This is how Lazaro's family was identified, and the visit now affords him his first opportunity to narrate what happened to his son and have that information recorded.

The interviewer asks the couple standard questions and matches their answers to the choices provided in the application's template.

It's a highly sensitive and skilled job - and one which field interviewer Nicholas Mbwana can see is made easier by using a mobile phone.

"We go to the households, ask about the causes of death - what really happened - and we also record the GPS in order to trace the household in future," he told the BBC.

Dr King says the system is key to the success of the project.

"GPS gives us the location of every household in the district so we can actually plot out on a map where people are dying of what, which means that you could design more sophisticated programs for targeting specific interventions."

The bigger picture

Mobile phone autopsies are being used on a limited scale at present. But the long term aim is to roll out the technique much more widely.

"The beauty of the system is that it's standardised and can be translated into any language you want," says Dr Bird.

"It's important when you're collecting data on a large scale that everyone is answering the same question, so that you know that the results are directly comparable from town to town and country to country."

Interviewees' answers are inputted directly into the mobile phone app

The World Health Organization (WHO) is already supporting the initiative and is working with institutions from the UK to Sweden to develop the technology further.

The data is currently being collected in a range of databases that can be accessed by researchers interested in public health.

As the project grows, researchers from the University of Umea in Sweden will co-ordinate the growing number of translations and the distribution of the technology around the world.

The government in Malawi is already keen to see the results of the project.

"It is important for us as a ministry to know what is killing Malawians out there so that we can plan ahead and put appropriate interventions in place to prevent that - and also to put out health messages," says Dr Charles Mwansambo, Malawi's Health Secretary.

The Ministry of Health has so far only been using information collected from medical facilities, which the health secretary concedes is biased data.

"We need comprehensive data from the hospitals and the community to plan well. We find ourselves planning for the small community that comes to hospital, not realising there is a bigger community out there that we need to budget for," he adds.

Significant inroads

Dr Mwansambo also acknowledges that a cultural practice of burying health documents with the dead makes it difficult to collect important information about deaths.

"When somebody dies people want to forget everything about them - those memories that will remind them of their loved ones. So unfortunately they bury the health passport along with their clothes and other possessions and we lose vital information in the process," he explains.

The health passports are documents issued to parents, which record the birth weight of the baby and its gain over time, as well as which immunizations were administered and when.

An elder at Mzangawa village, Kangkwamba Piri, is already talking to members of his community to drop that cultural practice.

"We've been doing this for a long time but it is wrong. What needs to be done is not to bury the documents and that's what we're encouraging people to do," he says.

For now, it is likely that millions of deaths will still go unnoticed by official figures. But verbal autopsies recorded on mobile phones are making small but significant inroads into solving the problem.

And for and his wife Magdalena, the chance to give information about what killed their child to an official is important.

Magdalena says: "What I have learnt from this interview will help me take care of my third baby so he can be healthy and live long."