Microscopic 'bacterial zoos' built out of jelly

- Published

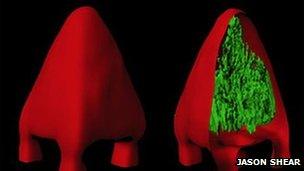

Bacteria, green, in their zoo, coloured red

A "bacterial zoo" with microscopic cages built out of jelly has been constructed by US scientists.

Their findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external, could transform understanding of how bacteria behave in communities.

The bugs have different properties, which can make infections hard to treat, when they form colonies.

UK researchers said bacterial communities were poorly understood and the technology could lead to progress.

Big groups of bacteria can acquire antibiotic resistance where lone bacteria would be vulnerable. The nature of a community can affect how serious an infection becomes in open wounds or in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis.

Upgrade

Scientists have been growing bacteria in Petri dishes in the laboratory for more than a century.

But they do not replicate all the conditions inside the body and they cannot be used to manually build colonies of bacteria, one bacterium at a time.

A team of researchers at the University of Texas have used 3D printing to build colonies.

They mixed bacteria with a special form of gelatin and let it set so the bacteria were suspended like cocktail fruit in jelly.

They then fired a laser at the gelatin-bacteria mix.

The structure of the gelatin was altered at the point the laser beam was focused. The targeted gelatin proteins hooked up to each other so that when the rest of the gelatin was washed away it left the "cage".

It allowed the researchers to build cages around individual, or small groups of bacteria in whatever shape they chose. By building up a number of cages, they could eventually build a "zoo", with every bacterium exactly where the researchers wanted it.

The walls of the cage were able to keep the bacteria in place, but allow nutrients and signals to pass between cages.

Prof Jason Shear, from the University of Texas, said experiments had shown that one species of bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus, could become more antibiotic resistant when growing with another Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

He told the BBC that the new technology could start to tackle questions about bacterial communities: "If a cluster develops antibiotic resistance, how large does it have to be, how many cells, what density is needed, is a low oxygen environment key?

"We're starting to see that it really does matter how cells arrange themselves, it affects how antibiotic resistant a colony is, so it may ultimately inform therapies."

Prof Ross Fitzgerald, from the Roslin Institute at the University of Edinburgh, said: "I think it is safe to say we know very little about bacterial communities.

"There are millions of bacteria in the gut, but we don't know much about how they function or relate to each other and infectious diseases are often caused by more than one pathogen, co-infection is more common that we'd thought in the past.

"I think this technology does provide an opportunity to simulate better in the laboratory various bacterial communities that can be present in an infection."

- Published5 September 2013

- Published9 August 2013

- Published25 March 2013