First human trial of new bone-marrow transplant method

- Published

Mohammed started going to school in September

Doctors at London's Great Ormond Street Hospital have carried out a pioneering bone-marrow transplant technique.

They say the method should help with donor shortages since it does not require a perfect cell match.

Mohammed Ahmed, who is nearly five years old, was among the first three children in the world to try out the new treatment.

He has severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome and had been waiting for a suitable donor for years.

Mohammed, who lives in Milton Keynes, was referred to Great Ormond Street Hospital when he was a year old.

His condition - a weak immune system - makes him more susceptible to infections than most, and a bone marrow transplant is the only known treatment.

While Mohammed was on the transplant waiting list, he became extremely sick with swine flu.

At that time, his doctors decided Mohammed's only real hope was to have a mismatched bone-marrow transplant, with his father acting as the donor.

Mohammed's dad, Jamil, agreed to give the experimental therapy a go.

Before giving his donation, Jamil was first vaccinated against swine flu so that his own bone-marrow cells would know how to fight the infection.

Mohammed's doctors then modified these donated immune cells, called "T-cells", in the lab to engineer a safety switch - a self-destruct message that could be activated if Mohammed's body should start to reject them once transplanted.

Safety net

Rejection or graft-v-host disease is a serious complication of bone-marrow transplants, particularly where tissue matching between donor and recipient is not perfect, and is one of the most difficult challenges faced by patients and their doctors.

Mismatched transplants in children - where the donor is not a close match for the child - are usually depleted of T-cells to prevent graft-v-host disease, but this causes problems in terms of virus infections and leukaemia relapse.

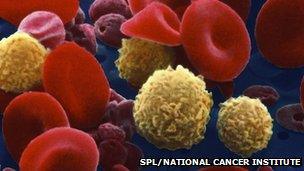

White blood cells protect the body against infections

The safety switch gets round this - plenty of T-cells to be transfused and later killed off if problems do arise.

Thankfully, the transplant carried out in 2011 was a success - Mohammed's doctors did not need to use the safety switch.

Although Mohammed still has to take a number of medicines to ward off future infections, his immune system is now in better shape.

Jamil said: "We waited for a full match but it did not come. By the grace of God, we took the decision to have the treatment.

"Now he is all right. Sometimes we forget what he has been through. We are just so grateful."

He said Mohammed would still need close monitoring and regular health checks over the coming years, but his outlook was good.

Dr Waseem Qasim, consultant in paediatric immunology at Great Ormond Street Hospital and lead author for the study, said the new approach should hopefully mean children who received a mismatched transplant could enjoy the same chance of success as those given a fully matched transplant.

"We think Mohammed is cured of his disorder. He should be able to lead a fairly normal life now."

A full report about Mohammed's therapy and the research by Great Ormond Street Hospital, King's College London and the Institute of Child Health has just been published in PLoS One journal.

There are currently about 1,600 people in the UK waiting for a bone-marrow transplant and 37,000 worldwide.

Just 30% of people will find a matching donor from within their families.

Donations involve collecting blood from a vein or aspirating bone marrow from the pelvis using a needle and syringe.

- Published22 October 2013

- Published29 September 2013

- Published3 July 2013