How older people with HIV are facing the future

- Published

Isolation and fear of the future can affect those living with HIV

In common with many people diagnosed with HIV in the 1980s, Danny West thought he had just months to live.

He became ill, watched friends die and prepared for his own demise at the hands of what was then an unknown virus.

Nearly 30 years on, Danny, who is from London, is one of the longest-surviving people in the world with HIV.

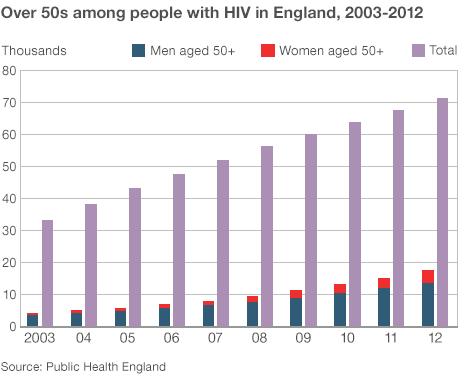

He is part of a growing group of around 19,000 adults aged over 50 receiving care for human immunodeficiency virus in the UK, many of them kept alive thanks to improvements in drug treatments.

Lost friends

Recently, the UN called for the "ageing" of the HIV epidemic to be taken seriously. It wants more services to be made available to this age group, who are now facing old age.

But, for many, life with HIV has been an emotional and physical rollercoaster.

Danny says he never thought he'd see 50.

"I was given a year at most. I was 24, I'd just got my social work qualification and my foot on the career ladder, and it was all whipped away in one moment.

"There was no treatment then. Over the next two years after my diagnosis, all of my peers died. Everyone went down like cards. My community was gone."

Danny has never been able to get a mortgage and does not have a pension. Despite working in the public sector and for HIV charities for many years, he has no idea what the future holds.

Many older people with HIV have serious money worries

"I haven't prepared myself psychologically for growing older. My body is ageing faster than a normal person's. I've got arthritis and osteoporosis and I live in constant physical pain.

"But the real issue for me is poverty - I don't know how I will cope financially."

Money worries

A recent study of people over 50 living with HIV by the Terence Higgins Trust, an HIV charity, found that Danny's concerns were not unusual.

The 50 Plus report, external showed that older people with HIV are financially disadvantaged compared with their peers and have serious worries about money, poor health, housing and social care.

Lisa Power, policy director at THT, says this is because many people became ill and had to give up work after their diagnosis. Others sold up, cashed in their pensions, went round the world and waited to die.

As "brilliant" anti-retroviral drugs started prolonging lives, she says, "benefits were cut for people who hadn't made provision for their old age, leaving many of the older HIV group living on a basic state pension".

"We found huge poverty in our study, particularly among those who thought they had a death sentence. Now we're coming round to understanding that people with HIV have a normal life expectancy."

For those diagnosed in recent years, the treatment is straight forward and they can carry on working and raise a family. But for those diagnosed back in the 1980s, the HIV journey has been considerably more traumatic.

Early side effects

Doctors still do not yet fully understand the impact of HIV on the ageing process.

Some health problems in older HIV patients may be related to the early treatments they received, which had significant and sometimes toxic side effects, rather than the virus itself.

But there is generally thought to be an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, heart disease, strokes and cancers in people with HIV.

Dr David Asboe, a consultant in HIV medicine and sexual health at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital and chairman of the British HIV Association, says more than half of the HIV patients he sees are over the age of 50, and some are even in their 80s.

"The earlier they are diagnosed, the earlier we can get them into treatment and that's important. If there is a delay then that's when the mortality risk increases."

The psychological effects of HIV on this group are all too obvious, he says.

"They should be able to work, but there is a real loss of confidence, and it can change the way people consider relationships with their family and wider society."

Myth and reality

HIV charities say that healthcare professionals, such as GPs, need to understand more about HIV and home carers should be given more training. Too often, patients don't have the confidence to disclose their status to their doctor or talk about their problems.

Danny says that previously any health problems he had would have been dealt with by a specialist consultant but changes mean that he now has to see his GP first for everything, which is unhelpful and frustrating.

According to Lisa Power, there are still too many myths surrounding HIV and more public awareness is needed.

"One group thinks there is a cure for it, another thinks it's a death sentence. The reality is that people with HIV have a managed, chronic condition - but they also have a life."

Danny has recently been forced to moved into damp, cold social housing in an area where he knows no-one, where he is facing the future with HIV alone.

"I don't have a picture of what I will be doing in the next 10 years. There are lots of uncertainties and unknowns.

"I live in fear of ill health, poverty and isolation. That's what I lie in bed thinking and worrying about."

- Published21 November 2011

- Published30 November 2011

- Published1 September 2011

- Published23 November 2010