Jungle Fever: The Exotic Disease Detectives

- Published

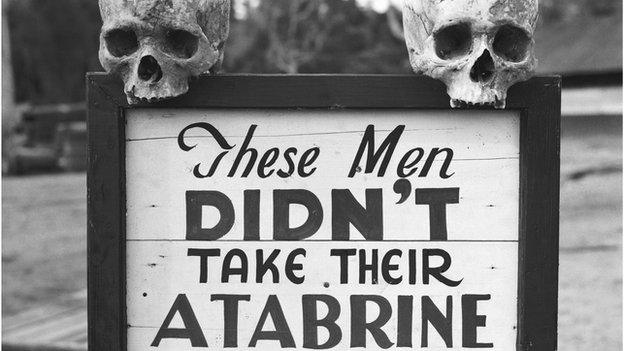

People have long been warned about the dangers of tropical diseases

When a patient goes to the doctor, most expect to come out with a diagnosis. But what if your disease is a mystery? Then it's time to call in the exotic disease detectives.

"I travelled to Peru last summer and about a month afterwards noticed what looked like a large boil," says Bob Gilbert, who lives in east London.

"It was continuously scabbing over. I couldn't understand it."

After waiting three weeks for it to clear up, Mr Gilbert finally visited his GP and was given a course of antibiotics.

This was followed by two further GP visits, investigations at four different hospitals and concerns about both tuberculosis and cancer.

It was only after being referred to the Hospital of Tropical Diseases in London that he finally received the correct diagnosis - New World cutaneous leishmaniasis.

"When I saw him, I was able to make the connection based on his travel history," says Diana Lockwood, a consultant at the hospital and a professor of Tropical Diseases.

"We were then able to confirm the diagnosis by performing a test on a sample of the ulcer."

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease spread by bites from infected sand flies. In most cases, it causes open sores on the skin (cutaneous leishmaniasis) but it can also infect and damage the organs (visceral leishmaniasis).

However symptoms can take weeks or months to develop - meaning that many people might not make the link to their foreign travel.

This can lead to a delay in diagnosis, and in the case of leishmaniasis, the risk of severe scarring and the destruction of tissue in the nose and throat.

But Mr Gilbert is not alone in coming back with something other than a suitcase full of dirty washing.

Every year thousands of UK residents are diagnosed with so-called imported diseases - and it's down to experts based at tropical disease centres in London and Liverpool to track them down and find the right treatment.

"I feel very relieved to have a diagnosis," says Mr Gilbert, "and feel grateful to have a health service that will pursue something so doggedly."

Unwelcome souvenirs

The difficulty with diagnosing exotic diseases is the sheer range of conditions that doctors face.

"We get lots of people coming to our walk-in clinic, with everything from diarrhoea to fevers and skin diseases," says Prof David Mabey, a consultant at the Hospital of Tropical Diseases in London.

"Many people have nothing to worry about, some have self-limiting viral infections. But from time to time we also see more serious conditions such as Lassa fever and Ebola," he told the BBC.

But despite the weird and wonderful conditions people can pick up abroad (see box), the key concern for tropical disease doctors is spotting the signs of malaria.

"We see well over 1,000 cases of malaria in the UK each year and although exact numbers vary, we could expect up to around 10 of those to die," says Prof Mabey.

The latest figures from Public Health England and the Malaria Reference Laboratory reveal that almost three-quarters of malaria cases were caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

This is the strain of malaria most likely to be fatal.

Prof David Lalloo, a tropical disease expert at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, says that in up to 80% of cases people travelling to see family - rather than holiday-makers - are most at risk of contracting malaria.

"People visiting friends and relatives often don't get travel advice because they don't see it as exotic travel, even though they tend to go to environments that are more risky than those chosen by the average traveller," he says.

"They can also assume that they have immunity to diseases such as malaria, especially if they lived abroad when they were younger. But people start to lose that immunity within two to three years, meaning they are no more protected than a child."

Exotic diseases on the rise

Wherever and however people pick them up, cases of imported disease are on the rise. And new ones are appearing too.

One example is chikungunya - a viral disease that causes fever and severe joint pain.

It originally emerged in East Africa but has since been spreading around the tropics to places including India and, more recently, the Caribbean - both popular destinations for UK residents.

This has made it much easier to catch.

But diagnosis isn't always straightforward, as the symptoms are at first glance very similar to the much more common viral disease, dengue.

This is where the services of the Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory at Porton Down come to the rescue.

Dr Emma Aarons is one of the doctors there who work to find definitive diagnoses as quickly as possible.

"Diagnosis is prognosis," says Dr Aarons.

"So if we know that someone has chikungunya instead of dengue, then we also know that although they may have joint problems that could be troublesome for many months, unlike some cases of dengue, this infection is not life threatening," she told the BBC.

"Knowing what the infection isn't can be just as important as knowing what it is."

Leaving on a jet plane

So what can people do to stay safe?

"Most vaccinations take a week to 10 days to give you full protection," says Prof David Lalloo of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

"So people need to think ahead, book an appointment with their GP or travel clinic and know where they plan to travel in some detail."

Even with malaria tablets, travellers should try to avoid mosquito bites in order to reduce their risk of catching dengue or chikungunya - diseases for which there are no vaccines or cures.

And if you do think you might have an exotic disease, Prof Lalloo says, speed is of the essence.

"If you look at the small number of deaths from malaria, you can see that they all involve a delay in diagnosis," he told the BBC.

"With malaria, just one to two days can make a difference as symptoms can escalate rapidly. So people should always mention any foreign travel to their doctor."

For Bob Gilbert, his path to a diagnosis of leishmaniasis was long and stressful. But he remains philosophical about his experience.

"I certainly didn't connect it to the trip at the time, and don't resent anyone for not spotting it immediately," he says.

"I chose to go on that holiday and took all the medications and creams they tell you to take. It was just the one that I got wasn't one I knew to look for."