A Sliding Doors moment for the NHS?

- Published

- comments

Sliding Doors is a film that strikes a chord with many people.

It alternates between two parallel universes based on the two paths the central character's life could take depending on whether or not she catches a train.

In chaos theory this is known as the butterfly effect, in which a small change at one place can result in large differences in a later state.

Life - as it was for Gwyneth Paltrow in the 1998 movie - is full of these "what if?" moments. The same is true for the NHS.

Take the debate about integrated care - or joined-up care as it is sometimes called. This is an unexciting word for what everyone agrees is one of the most pressing issues of our time.

As medicine has advanced and led to more life-saving treatment, an increasing amount of the NHS budget has come to be spent on long-term conditions.

Many of these are related to old age and involve managing illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease and respiratory problems.

This often requires coordinated care between the health and care sectors.

The problem is that one is free and provided by the NHS, while the other is means-tested and overseen by councils.

It means vulnerable people fall through the cracks as they are passed between the two.

'No big bang'

Both the government and Labour want this addressed.

Ministers are planning to launch the £3.8bn-a-year Better Care Fund next year off the back of 14 pilot schemes running this year looking at different ways of getting the two sectors to work together.

But that is small change - it doesn't even amount to 3% of the combined budgets for the two sectors.

This week saw the publication of the recommendations from a Labour-created independent commission led by Sir John Oldham, a GP and former Department of Health official.

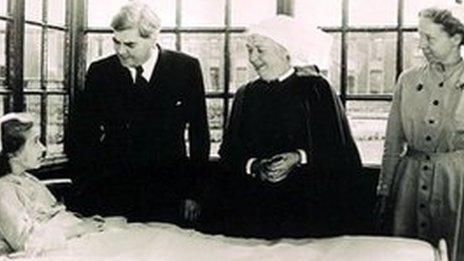

Aneurin Bevan insisted local government should not be given responsibility for the NHS

But they attracted little attention, proposing even less - £10bn from the NHS over the course of the next Parliament - be set aside. Although to be fair to Sir John, he was working under tight parameters - no reorganisation and no extra money.

Yet behind the scenes all the main political parties have talked about biting the bullet and merging the budgets to ensure integrated care becomes a reality. So why has none gone further?

People from both sides of the political divide say there is simply no appetite for another major shake-up of the NHS. Or as one person put it to me: "Andrew Lansley's reforms have poisoned the well."

But this wasn't even integrated care's first Sliding Doors moment.

Prior to the creation of the NHS in 1948, three-quarters of hospital beds were run by councils.

But when Aneurin Bevan started drawing up plans for a national health service after World War Two, he decided they could not be trusted to run a system on such a grand scale. So he proposed the giant central structure that still largely exists today.

The decision prompted a series of rows with Deputy Prime Minister Herbert Morrison, but Bevan won the argument and the rest, as they say is, history.

The combination of the two moments means today the plans being put forward are arguably just tinkering around the edges.

Richard Humphries, the King's Fund's expert on integrated care, believes this is unsustainable.

"The current structures with local authorities, clinical commissioning groups and NHS England are so complex and fragmented that they will have to change," he says.

"This is the elephant in the room, but the changes will be evolutionary now. There will be no big bang."