Widow wins frozen sperm legal fight

- Published

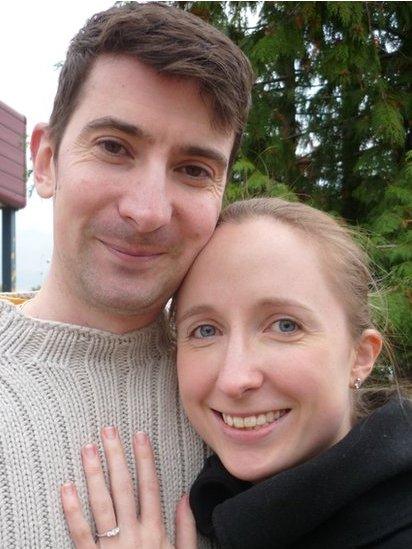

Beth Warren "absolutely delighted" after winning the right to prevent her dead husband's frozen sperm from being destroyed

A woman has won a legal battle to stop her dead husband's frozen sperm being destroyed.

Beth Warren's husband had sperm frozen before starting cancer treatment and signed paperwork saying his wife could use the sperm after his death.

He died from a brain tumour two years ago, but regulations meant his sperm were due to be destroyed in April 2015.

The High Court has backed her case, but the regulator has already announced plans to appeal against the decision.

The couple, who were together for eight years, married in a hospice six weeks before his death and she subsequently changed her surname to Warren.

Deadline

The law allows sperm and eggs to be stored for up to 55 years, if consent is regularly renewed.

But when 32-year-old Warren Brewer, a ski instructor, died of a brain tumour in February 2012, consent could no longer be renewed.

Beth Warren and Warren Brewer were together for eight years

The regulators, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), said the sperm could not be stored beyond April 2015.

But lawyers representing Mrs Warren, 28, from Birmingham, told the High Court judge that the regulator was taking an "excessively linguistic and technical approach".

In her judgement, external, Mrs Justice Hogg said: "The evidence indicates that both Mr Brewer and his wife were in agreement. He wanted her to have the opportunity to have his child, if she wanted, after his death."

But, she continued, the "written consents provided by Mr Brewer did not specify that his gametes should be stored beyond the statutory period" required by the HFEA.

She ruled that it was "right and proper, and proportionate" to allow the sperm to be kept until at least April 2023.

'Huge decision'

Mrs Warren said she was "over the moon" and "elated" with the decision.

She told the BBC: "It's beyond words, I hadn't even anticipated that I would feel that happy about it.

"I hadn't let myself believe I would get that outcome because I knew it really could have gone either way."

Her brother died in a car accident just weeks before her husband died.

She said that at that emotional time a forced deadline was not the reason to have a child and that she needed the time to "establish myself emotionally, financially and professionally" before choosing to have a child.

Mrs Warren said she had not decided what she would do now, as she had not let herself believe she could win.

At the start of the legal bid, Mrs Warren said it would be a "huge decision" to have a child who would never meet their father.

She added: "I cannot make that choice now and need more time to build my life back.

"I may never go ahead with treatment but I want to have the freedom to decide once I am no longer grieving."

'Wider implications'

However, this is not the end of the legal battle as the HFEA has asked for leave to appeal against the decision.

In a statement, the authority said: "We had hoped that the court could find a way for Mrs Warren to store the sperm for longer without having wider implications for the existing consent regime.

"However, because the judgment acknowledges that written consent to store the sperm beyond April 2015 is not in place, the judgment may have implications for other cases in which the sperm provider's wishes are less clear."

Mrs Warren's lawyer, James Lawford Davies, had said the regulations created injustice.

"Common-sense dictates that she should be allowed time to recover from the loss of her husband and brother and not be forced into making such an important reproductive choice at this point in her life."

He also said the regulations created inconsistencies.

There are no restrictions on exporting the sperm so they could be used in fertility treatment in another country.

The sperm could also be used to create embryos, which could be frozen and stored for seven years.

- Published4 December 2013

- Published4 December 2013